Authors: Goldsmith GR1, Berry ZC1, Lehmann MM2

Reviewer: Cernusak LA3

Measurement unit: carbon assimilation per unit water loss (e.g. mmol CO2 mol-1 H2O); Measurement scale: plant tissues; Equipment costs: €€; Running costs: €; Installation effort: low; Maintenance effort: low to medium; Knowledge need: low to medium; Measurement mode: manual and data logger

Water-use efficiency (WUE) is a measure of the carbon gained by plants through photosynthesis relative to the water lost through transpiration, defined a

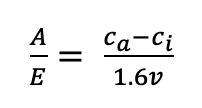

![]() (1)

(1)

where A is net photosynthesis and E is transpiration. This is commonly referred to as instantaneous WUE (Farquhar & Richards, 1984). However, both A and E are functions of the resistance to water movement (generally quantified as stomatal conductance; gs) and the driving gradient for diffusion of CO2 and H2O across the leaf surface, such that

(2)

(2)

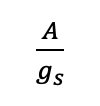

where ca is the mole fraction of CO2 in the ambient atmosphere, ci is the mole fraction of CO2 inside the leaf, 1.6 is the diffusion of H2O in air relative to that of CO2 in air, and v is the vapour pressure difference between inside the leaf and the ambient atmosphere. Therefore, instantaneous WUE can depend on environmental conditions, as differences in the vapour pressure of water in the air can vary significantly and lead to significant differences in E. To improve the ability to compare across studies without these confounding effects, intrinsic WUE (iWUE; Osmond et al., 1980) was proposed, defined as

(3)

(3)

There is considerable interest in measures of WUE at the leaf, whole plant, and ecosystem scale motivated by the importance of understanding the implications of climate change for both carbon and water cycling. For instance, there is already evidence that increases in atmospheric CO2 concentrations have increased WUE (Keenan et al., 2013). Long-term changes in temperature and precipitation are also likely to affect WUE by affecting the leaf-to-air vapour pressure difference and therefore altering rates of transpiration (Medrano et al., 2012). WUE provides an accessible measure of the effects of environmental stressors on the coupled processes of photosynthesis and transpiration and can thus contribute to our understanding of plant, species, and ecosystem functions in current and future climate scenarios.

5.15.1 What and how to measure?

Water-use efficiency is most commonly determined by measuring leaf gas exchange with an infrared gas analyser (IRGA), or by measuring whole plant biomass accumulation and water use (generally with potted plants). WUE is also inferred through measurements of the stable isotope ratios of carbon in plant organic matter, most commonly in plants with a C3 photosynthetic pathway. IRGA measurements are more direct and precise as well as instantaneous, but are difficult to scale to larger spatial and temporal scales (Medrano et al., 2015). Measurements on whole plants can be useful in particular experimental contexts, but have similar constraints (Cernusak et al., 2009). By comparison, stable isotopes of carbon integrate longer time periods, but must be interpreted very carefully in order to make inferences about WUE (Seibt et al., 2008).

Gas exchange

Measurements of the concentration of CO2 and H2O exchanged across a leaf surface serve as the primary means of quantifying WUE. This is done using commercially-available IRGAs that measure gas concentrations before and after air flows through a closed chamber containing a leaf or plant. These systems then calculate photosynthesis (A), transpiration (E), and stomatal conductance (gs) using equations that consider the flow rate, leaf area in the chamber, the ratio of stomata on both sides of the leaf, and the mole fractions of CO2 and H2O (von Caemmerer & Farquhar, 1981). Intrinsic and instantaneous WUE can be calculated from these three variables as described in Eqs. 1-3 above.

Measurements begin by identifying the leaf or plant of interest and clamping the chamber around the leaf. Most commonly these measurements are done on small leaf areas (6–10 cm2), although other chambers can be used or constructed to integrate over the leaf size of interest for the study. Both the leaves and the instrument should be allowed to equilibrate and be held under consistent conditions, controlling for light, temperature, relative humidity, and ambient CO2 for the duration of the measurement. WUE is known to vary on diurnal and seasonal cycles, as well as across light, temperature, and humidity gradients within canopies (Medrano et al., 2015). Research questions should consider this variability in their experimental design in order to ensure the ability to compare WUE across sample populations. Most commonly, WUE calculated from gas exchange is measured on fully sun-exposed and mature leaves during periods when stomatal conductance is non-limiting. This is usually during the late morning (09:00–11:00 hours) on sunny days where there are no extreme soil moisture deficits, unless studies are explicitly studying variation across one of these parameters.

Whole plant

Measurements of whole plant biomass accumulation relative to water use can serve as an alternative means of measuring WUE (Morison & Gifford, 1984; Marks & Strain, 1989; Centritto et al., 1999; Cernusak et al., 2009). This destructive method is carried out on smaller potted plants observed in an experimental context. Biomass accumulation (i.e. growth) is generally measured by comparing the dry weights of individual plants harvested at the beginning and end of the experiment. Water use is estimated by repeatedly weighing the potted plants on a balance to determine water use and returning each plant to field capacity (or the desired water content) on a regular basis between measurements. Control pots with soil, but no plants, can be used to estimate soil evaporation. However, evaporation should be minimised by covering the sides of pots with reflective materials, as well as by adding a layer of gravel to the soil surface (Cernusak et al., 2009). The biomass accumulation can then be divided by the cumulative water use (accounting for evaporation) to measure whole plant water-use efficiency.

δ13C of bulk plant tissues

An alternative means of inferring WUE is through the measurement of the ratio of the heavy to light carbon isotopes (i.e. 13C/12C, as interpreted relative to an international reference standard; Coplen, 2011) in plant tissues such as leaves and wood. The carbon isotope composition (δ13C) of plant tissue reflects the pathways for biochemical CO2 assimilation (i.e. C3 v. C4/CAM metabolism), as well as the plant functional response to climatic conditions. In C3 plants, the enzyme RuBisCO discriminates against the 13C in favour of the lighter isotope (12C) during photosynthetic CO2 assimilation, causing C3 plants to be more depleted compared to C4 and CAM plants. However, as leaf internal CO2 (ci) becomes limited relative to that of the ambient atmosphere (ca), discrimination against 13C necessarily decreases and the assimilation of 13C and its incorporation into plant material increases.

The calculation of ∆13C, which controls for the δ13C of the atmospheric CO2 used for assimilation as described below, can thus provide insights into ci/ca that can be used to infer the relationship between photosynthetic CO2 assimilation and water loss (Farquhar et al., 1982, 1989). Measurements of ∆13C are most commonly made on bulk leaf organic matter, reflecting a mix of both structural (e.g. cellulose) and non-structural carbohydrates (e.g. sugars, starch), as well as other compounds. Thus, bulk leaf organic matter mixes the signals integrated over the course of leaf formation and the signals integrated over recent (e.g. daily) CO2 assimilation. As such, the time scale reflected in ∆13C measurements differs from that of gas exchange.

The leaf material of interest should be excised and transferred to sampling bags or vials. Given that metabolic processes can continue even after the leaf is sampled, it is advisable (where possible) to quickly inactivate metabolic processes by using a microwave, submersion in liquid nitrogen, or storage on dry ice. Samples should subsequently be dried by oven at a maximum of 70 °C for 72h to constant weight (Pérez-Harguindeguy et al., 2013) or freeze dryer (Popp et al., 1996; Richter et al., 2009). The temperature and time for drying depend on the study question, how many samples are dried, the size, thickness and type of the plant material (e.g. large, fleshy or succulent leaves need more time) see protocol 2.1.1 Aboveground plant biomass for more details on the drying. Leaf material should be well milled and homogenised before being transferred into tin capsules. However, it is important to confirm that the material that is used during milling (e.g. reaction vials) is not causing any significant impact on the isotope ratio of a sample due to abrasion. Finally, the isotope ratios can then be measured by means of an elemental analyser coupled to an isotope ratio mass spectrometer (IRMS). Quality control standards and information on the long-term accuracy and precision of the instrumentation are important for appropriate interpretation of the results.

A similar procedure for drying and preparing samples, without the concerns of ongoing metabolic processes, can also be used to determine the δ13C of woody tissue. This type of sampling will reflect the δ13C integrated over longer time periods (e.g. in annual tree rings). However, the δ13C ratios of assimilates can be changed by post-photosynthetic isotope fractionation processes during translocation from leaves to downstream tissues and by mixing with older carbon from storage compounds such as starch. Interpreting the δ13C ratios in woody tissues thus requires additional considerations (Gessler et al., 2014).

δ13C of cellulose and non-structural carbohydrates

The structural and non-structural carbohydrate fractions in the leaf bulk material can be separated by different techniques, making inferences about δ13C possible at more specific time scales. For instance, the δ13C value from leaf cellulose reflects the predominant environmental conditions during leaf development, while δ13C measurements of the water soluble content (WSC), sugar, and starch reflect ∆13C values integrated over shorter time scales (Gessler et al., 2009).

For the extraction and purification of leaf cellulose for isotope analysis, leaf material is cut into small pieces and transferred into Teflon bags (Boettger et al., 2007). Lignin is first removed by submerging the bags in acidic NaClO2. The leaf material is then freed from fatty acids, oils, and hemicellulose with NaOH. Finally, it is cleaned with deionised water and HCl solutions. The remaining residue is then oven- or freeze-dried and can be used directly for analysis. However, some labs further homogenise the cellulose material by ultrasonication (Weigt et al., 2015). Infrared spectroscopy can be used to test the efficiency of the cellulose purification against standards (Rinne et al., 2005).

The WSC of bulk plant tissue (i.e. leaf or roots) can easily be extracted by mixing the tissue with water or methanol chloroform water (MCW) solutions and heating them for a short time in a water bath (Richter et al., 2009; Lehmann et al., 2015). If water is the only solvent used for extraction, the supernatant and the insoluble material can be used after centrifugation for sugar and starch purification, respectively. By contrast, if MCW is the solvent used for extraction, the chloroform phase must be removed by bench or oven drying to avoid a significant bias in isotope ratios of sugars and starch.

To measure the δ13C of bulk sugars, the WSC fraction must be isolated from non-sugar compounds such as amino acids, organic acids, and polyphenols. This can be done by ion exchange chromatography (Rinne et al., 2012; Lehmann et al., 2015). The WSC fraction is added on the top of the ion exchange material, gravimetrically passed through the columns/cartridges using deionised water, and the flow-through containing the neutral sugar fraction collected by reaction vials. In addition, starch is enzymatically isolated from the insoluble material after several washing and heating steps using heat-stable alpha amylase (Wanek et al., 2001; Richter et al., 2009), which breaks down the starch to a mix of sugars (i.e. glucose and maltose).

Aliquots of all bulk fractions, including WSC, sugars, and starch are then pipetted to tin capsules and oven-dried at 60 °C until completely dry. As above, the isotope ratios can then be measured by means of an elemental analyser coupled to an isotope ratio mass spectrometer (IRMS).

Where to start

Cernusak et al. (2009, 2013), Farquahar & Richards (1984), Farquhar et al. (1989), Medrano et al. (2015)

Interpretation

Gas exchange. Both the instantaneous WUE (A/E) and the intrinsic WUE (A/gs) can be calculated from gas exchange measurements. Instantaneous WUE is a more direct quantification of the trade-off between carbon and water, but is often difficult to compare across environments due to variations in leaf-to-air vapour pressure across measurement periods. In contrast, intrinsic WUE only considers stomatal aperture and is therefore independent of atmospheric demand of moisture (Osmond et al., 1980). Values of WUE vary across species and environmental conditions. General values for instantaneous WUE range from 2 to 11 mmol CO2 mol-1 H2O in woody C3 plants, while values tend to be higher in C4 and CAM plants (as high as 20 mmol CO2 mol-1 H2O) (Lambers et al., 2008). This greater WUE in C4 and CAM plants reflects the adaptive regulation of water loss associated with these photosynthetic pathways. There is also wide variation in intrinsic WUE values ranging from around 10 μmol mol-1 to over 200 μmol mol-1 (e.g. Flexas et al., 2013; Tomás et al., 2014).

Interpretation and comparison of WUE values require some consideration of the environmental conditions in which measurements were taken. Stomatal conductance plays a key role and WUE tends to increase as stomata close (Condon et al., 2002; Tomás et al., 2014). Given that drought typically reduces stomatal conductance to minimise water loss, there is evidence that WUE will continue to increase under the drier conditions associated with current and projected global warming (Pou et al., 2008; Beer et al., 2009). There is much literature considering the effects of increasing atmospheric concentrations of CO2 on WUE. This research has found support for a so-called “fertilisation effect,” whereby closures in stomatal aperture maintain a consistent leaf internal CO2, but decrease water loss: this results in increased WUE (Keenan et al., 2013; Frank et al., 2015).

Whole plant. Measurements of whole-plant WUE require some additional considerations of potential sources of error. Rather than repeat measurements on individual plants, the destructive nature of the approach necessitates that biomass accumulation be estimated from two different sets of individuals and this may serve as a source of random error with respect to carbon gain. In addition, whole plant measurements made over days or weeks are subject to the additional influences of i) water lost through transpiration that is not associated with carbon gain (e.g. night-time transpiration; Dawson et al., 2007) and ii) the offset of carbon gain by respiratory carbon losses through stems and roots during the day, as well as through stems, roots, and leaves during the night (Cernusak et al., 2007). The magnitude of these effects on whole-plant WUE is not well studied, although research indicates that they are not likely to outweigh differences among species or between experimental treatments (Centritto et al., 2002; Cernusak et al., 2007, 2009). Notably, night-time transpiration and respiration may lead to a disconnect between leaf-level and whole plant measures of WUE (Medrano et al., 2015). If expressed in terms of the carbon content in the plant dry mass increment per unit water lost from the plant, typical values of whole-plant WUE will be about half those measured at the leaf level, mainly reflecting respiratory carbon losses.

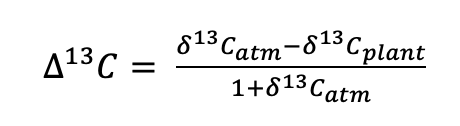

δ13C. For the purposes of inferring WUE, measurements of δ13C are generally interpreted in terms of discrimination (∆13C), defined as

(4)

(4)

where δ13Cplant is the carbon isotope composition of plant organic matter and δ13Catm is the carbon isotope composition of atmospheric CO2. It should be noted that ∆13C generally results in positive values for plant organic matter, whereas δ13C is generally negative (when interpreted relative to the standard VPDB): this can cause confusion when studies differ in their presentation of results. The calculation of ∆13C has the advantage of allowing for the interpretation of carbon isotope composition in the absence of any confounding effects of differences in the δ13C of atmospheric source CO2 used by the plant for photosynthesis. While the atmosphere is generally well mixed, both spatial and temporal differences can arise. For instance, there can be differences in the δ13C of CO2 between the canopy and understorey, due to the influence of CO2 respired from the soil. The δ13C of CO2 has also changed considerably over time: the accelerated burning of fossil fuels has led to a c. 1.5 ‰ (relative to the standard VPDB) decrease in the δ13C of atmospheric CO2 since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution (Rubino et al., 2013) and this is an important consideration when interpreting long-term records (e.g. tree rings or herbarium specimens).

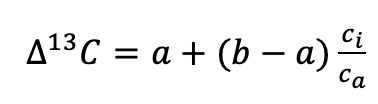

An important benefit of ∆13C is that it can be used as a means of approximating ci/ca. However, doing so differs based on the photosynthetic pathway of the species under consideration. Here we focus on an approximated relationship between ∆13C and ci/ca in plants with a C3 photosynthetic pathway, defined as

(5)

(5)

where a is the fractionation associated with diffusion of CO2 through the stomata to the sites of carboxylation (4.4 ‰), b is the fractionation associated with carboxylation (27 ‰), ci is the mole fraction of CO2 inside the leaf, and ca is the mole fraction of CO2 in the ambient atmosphere (Farquhar et al., 1982). Thus the ∆13C of plant organic matter increases with increasing ci/ca. In C3 plants, ∆13C ranges from c. 14 to 28 ‰ (Diefendorf et al., 2010). Alternatively, when the δ13C of atmospheric CO2 can be assumed to be constant, the δ13C of plant organic matter decreases with increasing ci/ca. In C3 plants, δ13C ranges from c. -21 to -35 ‰ (Diefendorf et al., 2010).

In many observations of plants with a C3 photosynthetic pathway, there is a very strong relationship between instantaneous ci/ca and δ13C (Cernusak et al., 2013). Given that ci/ca responds to the supply and demand for CO2 imposed by photosynthesis and stomatal closure to prevent water loss, this relationship can provide insights into WUE. In fact, the approximation of ci/ca from ∆13C has also been used to mathematically solve intrinsic WUE (A/gs). However, it is critically important to recognise that the relationship between ∆13C and WUE can break down because i) ∆13C is related to gs rather than E and therefore does not account for differences in vapour pressure difference that often occur in time-integrated measures and ii) ∆13C, as expressed in equation 5, is related to ci/ca rather than cc/ca (where cc is the mole fraction of CO2 in the chloroplast) and therefore does not account for the additional resistance against the diffusion of CO2 from the intracellular air spaces to the actual sites of photosynthetic carbon fixation. These limitations can lead to erroneous estimates and interpretations of intrinsic WUE (Seibt et al., 2008).

Compared to the C3 photosynthetic pathway, the structural and functional differences in the C4 and CAM photosynthetic pathways lead to considerable additional complexity for interpreting how changes in ∆13C may relate to changes in WUE. While a detailed explanation of these relationships is not within the purview of this protocol, a number of studies have developed the mechanistic basis for these relationships (Farquhar, 1983; Farquhar et al., 1989; reviewed by Cernusak et al., 2013; Ellsworth & Cousins, 2016), as well as gathered empirical data on the relationships as a function of different environmental conditions (Winter et al., 2005; Ellsworth et al., 2017).

5.15.2 Special cases, emerging issues, and challenges

Special cases

As noted above, information on the carbon isotope ratio alone cannot fully resolve the extent to which observed differences in ci/ca reflect changes in photosynthesis (A) or stomatal conductance (gs). Here, the coupled measurement of stable isotopes of oxygen (δ18O) and δ13C can provide additional insights (Scheidegger et al., 2000).

As described in protocol 5.13 Stable isotopes of water for inferring plant function, the δ18O of plant organic matter reflects the extent of evaporative enrichment of leaf water associated with transpiration. Evaporation of water from the leaf enriches the isotopic composition of the remaining leaf water due to i) an equilibrium fractionation associated with phase change from liquid to vapour and ii) a kinetic fractionation associated with diffusion through the stomata and boundary layer. The magnitude of this fractionation depends on the isotopic composition of both the source water and the atmospheric water vapour, as well as on the ratio of ambient air vapour pressure to leaf intracellular vapour pressure (Cernusak et al., 2016). The extent of this enrichment is subsequently recorded in plant organic matter through the incorporation of oxygen isotopes from water into photosynthetic products. Critically, δ18O is not mechanistically coupled to the drawdown of ci via photosynthesis.

The dual carbon and oxygen isotope approach relies on these established relationships between leaf gas exchange and isotopic fractionation to derive a series of model scenarios that can be used to distinguish whether a change in the 13C/12C of plant organic matter is likely to be the result of a change in photosynthesis (inferred by δ13C), or stomatal conductance (inferred by δ18O). As a result, this approach is particularly important for making statements about water-use efficiency using stable isotopes. Since its introduction, the approach has been applied in a number of different experimental contexts, including nutrient availability (Cabrera-Bosquet et al., 2011), CO2 and ozone (Grams et al., 2007), tree mortality (Herrero et al., 2013), and tree species mixtures (Grossiord et al., 2013). However, the interpretation of the approach is not always straightforward and additional care must be taken to draw meaningful conclusions (Roden & Siegwolf, 2012).

Emerging issues and challenges

There is growing recognition that estimates of water-use efficiency made at different scales (e.g. leaf, whole plant, ecosystem) using different methods (e.g. gas exchange, stable isotopes, eddy covariance) are not easily compared (Medlyn et al., 2017). This problem is particularly apparent in certain plant functional types (e.g. evergreen needle leaf, deciduous broadleaf forest, C3 grasslands). As noted above, the differences in methods and where those differences may lead to discrepancies should be considered carefully in interpreting data.

5.15.3 References

Theory, significance, and large datasets

Cernusak et al. (2013), Diefendorf et al. (2010), Farquhar et al. (1989), Siebt et al. (2008)

More on methods and existing protocols

Boettger et al. (2007), Cernusak et al. (2009), Medrano et al. (2012)

All references

Beer, C., Ciais, P., Reichstein, M., Baldocchi, D., Law, B. E., Papale, D., … Wohlfahrt, G. (2009). Temporal and among‐site variability of inherent water use efficiency at the ecosystem level. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 23(2), GB003233.

Boettger, T., Haupt, M., Knöller, K., Weise, S. M., Waterhouse, J. S., Rinne, K. T., … Schleser, G. H. (2007). Wood cellulose preparation methods and mass spectrometric analyses of δ13C, δ18O, and nonexchangeable δ2H values in cellulose, sugar, and starch: an interlaboratory comparison. Analytical Chemistry, 79(12), 4603-4612.

Cabrera-Bosquet, L., Albrizio, R., Nogués, S., & Araus, J. L. (2011). Dual Δ13C/δ18O response to water and nitrogen availability and its relationship with yield in field-grown durum wheat: Δ13C, δ18O and yield responses to water and N availability. Plant, Cell & Environment, 34(3), 418-433.

Centritto, M., Lee, H. S. J., & Jarvis, P. G. (1999). Interactive effects of elevated CO2 and drought on cherry (Prunus avium) seedlings I. Growth, whole-plant water use efficiency and water loss. New Phytologist, 141(1), 129–140.

Centritto, M., Lucas, M. E., & Jarvis, P. G. (2002). Gas exchange, biomass, whole-plant water-use efficiency and water uptake of peach (Prunus persica) seedlings in response to elevated carbon dioxide concentration and water availability. Tree Physiology, 22(10), 699-706.

Cernusak, L. A., Winter, K., Aranda, J., Turner, B. L., & Marshall, J. D. (2007). Transpiration efficiency of a tropical pioneer tree (Ficus insipida) in relation to soil fertility. Journal of Experimental Botany, 58(13), 3549-3566.

Cernusak, L. A., Winter, K., Aranda, J., Virgo, A., & Garcia, M. (2009). Transpiration efficiency over an annual cycle, leaf gas exchange and wood carbon isotope ratio of three tropical tree species. Tree Physiology, 29(9), 1153-1161.

Cernusak, L. A., Ubierna, N., Winter, K., Holtum, J. A. M., Marshall, J. D., & Farquhar, G. D. (2013). Environmental and physiological determinants of carbon isotope discrimination in terrestrial plants. New Phytologist, 200(4), 950-965.

Cernusak, L. A., Barbour, M. M., Arndt, S. K., Cheesman, A. W., English, N. B., Feild, T. S., … Farquhar, G. D. (2016). Stable isotopes in leaf water of terrestrial plants: Stable isotopes in leaf water. Plant, Cell & Environment, 39(5), 1087-1102.

Condon, A. G., Richards, R. A., Rebetzke, G. J., & Farquhar, G. D. (2002). Improving intrinsic water-use efficiency and crop yield. Crop Science, 42(1), 122-131.

Coplen, T. B. (2011). Guidelines and recommended terms for expression of stable-isotope-ratio and gas-ratio measurement results. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry, 25(17), 2538-2560.

Dawson, T. E., Burgess, S. S. O., Tu, K. P., Oliveira, R. S., Santiago, L. S., Fisher, J. B., … Ambrose, A. R. (2007). Nighttime transpiration in woody plants from contrasting ecosystems. Tree Physiology, 27(4), 561-575.

Diefendorf, A. F., Mueller, K. E., Wing, S. L., Koch, P. L., & Freeman, K. H. (2010). Global patterns in leaf 13C discrimination and implications for studies of past and future climate. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 107(13), 5738-5743.

Ellsworth, P. Z., & Cousins, A. B. (2016). Carbon isotopes and water use efficiency in C4 plants. Current Opinion in Plant Biology, 31, 155-161.

Ellsworth, P. Z., Ellsworth, P. V., & Cousins, A. B. (2017). Relationship of leaf oxygen and carbon isotopic composition with transpiration efficiency in the C4 grasses Setaria viridis and Setaria italica. Journal of Experimental Botany, 68(13), 3513-3528.

Farquhar, G. (1983). On the nature of carbon isotope discrimination in C4 species. Australian Journal of Plant Physiology, 10(2), 205.

Farquhar, G., & Richards, R. (1984). Isotopic composition of plant carbon correlates with water-use efficiency of wheat genotypes. Australian Journal of Plant Physiology, 11(6), 539.

Farquhar, G. D., O’Leary, M. H., & Berry, J. A. (1982). On the relationship between carbon isotope discrimination and the intercellular carbon dioxide concentration in leaves. Functional Plant Biology, 9(2), 121-137.

Farquhar, G. D., Hubick, K. T., Condon, A. G., & Richards, R. A. (1989). Carbon isotope fractionation and plant water-use efficiency. In P. W. Rundel, J. R. Ehleringer, & K. A. Nagy (Eds.), Stable Isotopes in Ecological Research (pp. 21-40). New York: Springer.

Flexas, J., Niinemets, Ü., Gallé, A., Barbour, M. M., Centritto, M., Diaz-Espejo, A., … Medrano, H. (2013). Diffusional conductances to CO2 as a target for increasing photosynthesis and photosynthetic water-use efficiency. Photosynthesis Research, 117(1–3), 45-59.

Frank, D. C., Poulter, B., Saurer, M., Esper, J., Huntingford, C., Helle, G., … Weigl, M. (2015). Water-use efficiency and transpiration across European forests during the Anthropocene. Nature Climate Change, 5(6), 579-583.

Gessler, A., Brandes, E., Buchmann, N., Helle, G., Rennenberg, H., & Barnard, R. L. (2009). Tracing carbon and oxygen isotope signals from newly assimilated sugars in the leaves to the tree-ring archive. Plant, Cell & Environment, 32(7), 780-795.

Gessler, A., Ferrio, J. P., Hommel, R., Treydte, K., Werner, R. A., & Monson, R. K. (2014). Stable isotopes in tree rings: towards a mechanistic understanding of isotope fractionation and mixing processes from the leaves to the wood. Tree Physiology, 34(8), 796-818.

Grams, T. E. E., Kozovits, A. R., HäBerle, K.-H., Matyssek, R., & Dawson, T. E. (2007). Combining δ13C and δ18O analyses to unravel competition, CO2 and O3 effects on the physiological performance of different-aged trees. Plant, Cell & Environment, 30(8), 1023-1034.

Grossiord, C., Granier, A., Gessler, A., Pollastrini, M., & Bonal, D. (2013). The influence of tree species mixture on ecosystem-level carbon accumulation and water use in a mixed boreal plantation. Forest Ecology and Management, 298, 82-92.

Herrero, A., Castro, J., Zamora, R., Delgado-Huertas, A., & Querejeta, J. I. (2013). Growth and stable isotope signals associated with drought-related mortality in saplings of two coexisting pine species. Oecologia, 173(4), 1613-1624.

Keenan, T. F., Hollinger, D. Y., Bohrer, G., Dragoni, D., Munger, J. W., Schmid, H. P., & Richardson, A. D. (2013). Increase in forest water-use efficiency as atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations rise. Nature, 499(7458), 324-327.

Lambers, H., Chapin, F. S., & Pons, T. L. (2008). Plant Physiological Ecology (2nd ed.). New York: Springer-Verlag.

Lehmann, M. M., Rinne, K. T., Blessing, C., Siegwolf, R. T. W., Buchmann, N., & Werner, R. A. (2015). Malate as a key carbon source of leaf dark-respired CO2 across different environmental conditions in potato plants. Journal of Experimental Botany, 66(19), 5769-5781.

Marks, S., & Strain, B. R. (1989). Effects of drought and CO2 enrichment on competition between two old-field perennials. New Phytologist, 111(2), 181-186.

Medlyn, B. E., De Kauwe, M. G., Lin, Y.-S., Knauer, J., Duursma, R. A., Williams, C. A., … Wingate, L. (2017). How do leaf and ecosystem measures of water-use efficiency compare? New Phytologist, 216(3), 758-770.

Medrano, H., Gulias, J., Chaves, M. M., Galmes, J., & Flexas, J. (2012). Terrestrial photosynthesis changing environment molecular physiological and ecological approach: Plant science. In J. Flexas, F. Loreto, & H. Medrano (Eds.), Terrestrial Photosynthesis in a Changing Environment: A Molecular Physiological and Ecological Approach (pp. 523-536). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Medrano, H., Tomás, M., Martorell, S., Flexas, J., Hernández, E., Rosselló, J., … Bota, J. (2015). From leaf to whole-plant water use efficiency (WUE) in complex canopies: Limitations of leaf WUE as a selection target. The Crop Journal, 3(3), 220-228.

Morison, J., & Gifford, R. (1984). Plant growth and water use with limited water supply in high CO2 concentrations. II. Plant dry weight, partitioning and water use efficiency. Australian Journal of Plant Physiology, 11(5), 375.

Osmond, C. B., Björkman, O., & Anderson, D. J. (1980). Physiological Processes in Plant Ecology: Toward a Synthesis with Atriplex. Berlin: Springer.

Pérez-Harguindeguy, N., Díaz, S., Garnier, E., Lavorel, S., Poorter, H., Jaureguiberry, P., … Cornelissen, J. H. C. (2013). New handbook for standardised measurement of plant functional traits worldwide. Australian Journal of Botany, 61(3), 167-234.

Popp, M., Lied, W., Meyer, A. J., Richter, A., Schiller, P., & Schwitte, H. (1996). Sample preservation for determination of organic compounds: microwave versus freeze-drying. Journal of Experimental Botany, 47(10), 1469-1473.

Pou, A., Flexas, J., Alsina, M. del M., Bota, J., Carambula, C., de Herralde, F., … Medrano, H. (2008). Adjustments of water use efficiency by stomatal regulation during drought and recovery in the drought-adapted Vitis hybrid Richter-110 (V. berlandieri × V. rupestris). Physiologia Plantarum, 134(2), 313-323.

Richter, A., Wanek, W., Werner, R. A., Ghashghaie, J., Jäggi, M., Gessler, A., … Gleixner, G. (2009). Preparation of starch and soluble sugars of plant material for the analysis of carbon isotope composition: a comparison of methods. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry, 23(16), 2476-2488.

Rinne, K. T., Boettger, T., Loader, N. J., Robertson, I., Switsur, V. R., & Waterhouse, J. S. (2005). On the purification of α-cellulose from resinous wood for stable isotope (H, C and O) analysis. Chemical Geology, 222(1-2), 75-82.

Rinne, K. T., Saurer, M., Streit, K., & Siegwolf, R. T. W. (2012). Evaluation of a liquid chromatography method for compound‐specific δ13C analysis of plant carbohydrates in alkaline media. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry, 26(18), 2173-2185.

Roden, J., & Siegwolf, R. (2012). Is the dual-isotope conceptual model fully operational? Tree Physiology, 32(10), 1179-1182.

Rubino, M., Etheridge, D. M., Trudinger, C. M., Allison, C. E., Battle, M. O., Langenfelds, R. L., … Francey, R. J. (2013). A revised 1000 year atmospheric δ13C‐CO2 record from Law Dome and South Pole, Antarctica. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 118(15), 8482-8499.

Scheidegger, Y., Saurer, M., Bahn, M., & Siegwolf, R. (2000). Linking stable oxygen and carbon isotopes with stomatal conductance and photosynthetic capacity: a conceptual model. Oecologia, 125(3), 350-357.

Seibt, U., Rajabi, A., Griffiths, H., & Berry, J. A. (2008). Carbon isotopes and water use efficiency: sense and sensitivity. Oecologia, 155(3), 441-454.

Tomás, M., Medrano, H., Escalona, J. M., Martorell, S., Pou, A., Ribas-Carbó, M., & Flexas, J. (2014). Variability of water use efficiency in grapevines. Environmental and Experimental Botany, 103, 148-157.

von Caemmerer, S., & Farquhar, G. D. (1981). Some relationships between the biochemistry of photosynthesis and the gas exchange of leaves. Planta, 153(4), 376-387.

Wanek, W., Heintel, S., & Richter, A. (2001). Preparation of starch and other carbon fractions from higher plant leaves for stable carbon isotope analysis. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry, 15(14), 1136-1140.

Weigt, R. Bräunlich, S., Zimmermann, L., Saurer, M., Grams, T.E.E., Dietrich, H.-P., … Nikolova, P.S. (2015). Comparison of δ18O and δ13C values between tree-ring whole wood and cellulose in five species growing under two different site conditions. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry, 29(23), 2233-2244.

Winter, K., Aranda, J., & Holtum, J. A. M. (2005). Carbon isotope composition and water-use efficiency in plants with crassulacean acid metabolism. Functional Plant Biology, 32(5), 381.

Authors: Goldsmith GR1, Berry ZC1, Lehmann MM2

Reviewer: Cernusak LA3

Affiliations

1 Schmid College of Science and Technology, Chapman University, Orange, USA

2 Forest Dynamics, Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research WSL, Birmensdorf, Switzerlans

3 College of Science and Engineering, James Cook University, Cairns, Australia