Authors: Konestabo HS1 & Kardol P2

Reviewer: Birkemoe T3

Measurement unit: abundance per area or gram soil; Measurement scale: plot; Equipment costs: €; Running costs: €; Installation effort: low to high; Maintenance effort: low to medium; Knowledge need: medium to high (taxonomic knowledge); Measurement mode: manual

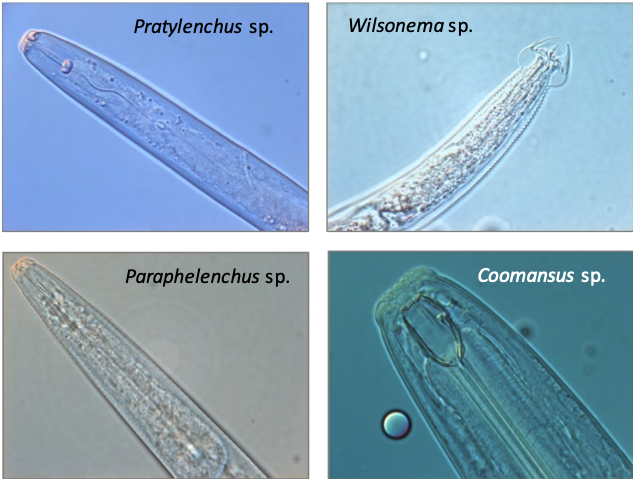

Soil micro- and mesofauna are small invertebrates of ~0.1–2 mm in length, living in soil or the litter layer. For microfauna, we focus on soil nematodes (also called roundworms), which are among the most numerous soil organisms in most terrestrial ecosystems with densities up to 3–4 million m-2 (Bardgett et al., 1999; Van den Hoogen et al., 2019). Soil nematodes also display high taxonomic and functional diversity. Based on the morphology of their mouth parts, soil nematodes can be attributed to one of the following feeding groups (Yeates et al., 1993; Fig. 4.10.1): 1) endo-parasitic plant-feeders (feeding from within the plant), 2) ecto-parasitic plant feeders (feeding on plant tissue from outside the plant), 3) bacterial feeders, 4) fungal feeders, 5) omnivores, and 6) carnivores. Endo-parasitic plant feeders enter the plant root and feed on deep cell layers, while ecto-parasitic nematodes feed from outside the plant on outer cortical cells and root hairs. Omnivorous nematodes feed on bacteria, amoebae, flagellates, and bacterial-feeding, fungal-feeding, and plant-feeding nematodes (Yeates et al., 1993), while carnivorous nematodes feed on other groups of nematodes and on other organisms such as enchytraeids (Yeates et al., 1993). Entomopathogenic nematodes are not considered in this protocol. Springtails (Collembola), mites (Acari), and enchytraeids or potworms (Enchytraeidae) are generally considered as mesofauna, while diplurans (Diplura), proturans (Protura), and jumping bristletails (Archaeognatha) are sometimes also included in this group. The mesofauna are a functionally diverse group, dominated by decomposers or detritivores, but also include microbivores, herbivores, fungivores, and predators. Mesofauna decomposers may feed directly on decaying organic matter, or on bacteria and fungi associated with detritus (Hopkin, 1997). Microbivorous mesofauna can be generalists, feeding on different kinds of bacteria and fungi, or have strong feeding preferences (Verhoef et al., 1988; Chen et al., 1995). Predatory mesofauna can be found within the Diplura, mites of the order Mesostigmata and the sub-order Prostigmata, and there are also some predatory springtails (e.g. Friesea sp.), feeding on other micro- and mesofauna. Mesofauna feeding activities may exert strong top-down control on decomposition processes in the soil through cascade effects on the activity of microorganisms, and may influence primary production and plant N accumulation (Santos et al., 1981; Setälä et al., 1998; Hedlund & Sjögren-Öhrn, 2000; Cortet et al., 2003). Species richness and functional diversity as well as abundance and biomass of mesofauna greatly influence soil decomposition processes (Setälä et al., 1991; Mebes & Filser, 1998; Cortet et al., 2003).

Together with macroinvertebrates and earthworms, micro- and mesofauna are important in driving litter decomposition, nutrient turnover, and plant productivity, and hence, how ecosystems respond to natural and anthropogenic environmental changes. Micro- and mesofauna are also important bio-indicators for effects of climate change on the functioning of terrestrial ecosystems as these organisms are sensitive to shifts in the soil environment (e.g. Kardol et al., 2010). Although the direct effect of small temperature changes (1–3 °C) on soil fauna may be small (Sjursen et al., 2005; Alatalo et al., 2015, 2017; De Long et al., 2016), changes in water availability, increased number of freeze-thaw cycles, changing plant cover and species composition, and changes in nutrient availability are expected to have larger impacts (Konestabo et al., 2007; Kardol et al., 2010; Elmendorf et al., 2012; Krab et al., 2015). Land-use change, nitrogen deposition, habitat disturbances, and plant invasions have all been shown to affect micro- and mesofauna abundance either directly or indirectly through effects on plant cover and soil biochemistry (Bardgett & Cook, 1998; Bedano et al., 2006; Hågvar & Klanderud, 2009; Leinaas et al., 2015). Because of the close relationships between micro- and mesofauna and other below- and aboveground communities, it is recommended to include these functionally diverse groups in studies of climate- and global-change effects on ecosystem functioning. Classifying micro- and mesofauna into functional groups is of particular interest as it informs on how climate change affects belowground trophic relationships and the flow of energy in soil food webs.

Here, we describe the recommended sampling methods for 1) extraction of nematodes from soils and from plant roots, and 2) extraction of soil and litter mesofauna.

4.10.1 What and how to measure?

Micro- and mesofauna are quantified by counting the number of individuals per area or per gram of soil and/or litter. Endoparasitic nematodes can also be quantified per gram of root tissue. Standardised sampling and extraction methods for soil invertebrates, including more details on some of the most common methods described here, can be found in ISO Standards 23611: 1-4 (ISO, 2006; 2007a, 2007b; 2018). Micro- and mesofauna are relatively stationary organisms compared to macroinvertebrates and insects (Ojala & Huhta, 2001 and references therein), and usually complete their life-cycle within the same habitat. However, the different taxonomic groups of micro- and mesofauna vary in size, activity level, and how they burrow into the soil matrix. Thus, there is not one single extraction method that will cover all organisms. Each method’s efficiency depends on a number of factors including soil properties, vegetation cover, the animal’s behavioural responses, their association with water or air pockets, and their tolerance to drought and heat.

Some soil organisms have inactive stages that will not be captured by active extraction methods (see below). Seasonal variation in abundance and vertical distribution are common and should be taken into account when comparing between years. The vertical distribution might also differ between life stages. Generally, large variation in abundances over a small spatial scale should be expected when comparing sites within or between growing seasons. To fully capture soil micro- and mesofauna responses to climatic changes, samples should be taken at different times across the years. Seasonal dynamics, and hence, the required number of samplings, depend on the climatic zone and on vegetation type (for example, evergreen vs. deciduous forests). But, generally 3–4 samplings would capture most of the seasonal variation. When resources only allow one sampling per year, soils are best collected at peak standing biomass, or towards the end of the growing season.

Soil core sampling

The most common sample unit for measuring micro- and mesofauna are soil cores.

For nematodes, small-diameter soil cores (1–5 cm diameter) are collected from the plot, typically using a tubular soil probe (Fig. 4.10.2). In order to get a representative sample of the plot, it is recommended to collect 5–20 small cores (subsamples) and bulk them into one composite sample per plot. Collecting several small samples is also less destructive to the plot than one large sample. The total size of the composite soil sample should be about 100–200 ml. The subsamples can be collected haphazardly, or according to a fixed sampling grid. Here, it is important to keep in mind the spatial configuration and heterogeneity of the plant community. Notably, soil samples collected from beneath individual plant species give different results compared to soil samples randomly collected across the plot (Kardol et al., 2010). Samples are often collected from the upper 10 cm of the soil profile (the litter layer is generally not included). However, depending on the research question and the type of ecosystem, samples can also be collected from greater soil depth (e.g. 0–10 cm, 10–20 cm, 20–30 cm). Alternatively, samples can be collected according to soil horizons or soil layers (e.g. O-horizon/humus layer, A- horizon/top soil, B-horizon/sub soil).

For mesofauna, intact soil cores including the litter layer are extracted from the habitat, using a metal soil corer (Fig. 4.10.2). Where the plant cover is low (typically mosses, lichens), the plant cover can be included in the sampled soil core. In habitats with a plant cover reaching above 2–3 cm in height, the plant cover can be removed by cutting it just above the litter layer, or gently bending it to the sides, exposing the soil and litter layer below. The soil cores should be large enough to include a representative estimate of the mesofauna without destroying the plots. Usually, a sample diameter of 4–10 cm is chosen depending on the heterogeneity of the habitat, plot size, and the extraction facilities available. Cores should be taken from a representative section of the habitat. A large core size demand less replicates; 3–12 replicates are commonly used. The depth of the cores depends on the habitat, but as mesofauna are most often found in the uppermost layers of the soil and in the litter layer, a depth of ~5 cm is often sufficient. It can, however, be useful to perform a pilot investigation of the patchiness and the soil profile before deciding on the sample size, depth, and replication.

Nematode extraction methods

Upon collection, soil and/or root samples for nematode extraction should be stored in plastic bags or containers, not be exposed to high temperatures during the sampling campaing (a simple cooler does the job), and be refrigerated (± 4°C) at the earliest opportunity. Samples should be extracted as soon as possible after collection although storage for 1–2 weeks is generally not a problem. Prior to extraction, bulk soil samples can be carefully passed through a 1-cm sieve and mixed well for homogeneity. Mixing should be done gently to avoid damage to the nematodes.

A variety of different methods have been developed for the extraction of free-living and plant-parasitic nematodes. The most commonly used methods can be classified based on the motility, the specific density, and the size of nematodes (EPPO, 2013). None of the methods allows extraction of all stages of all nematode taxa at 100% efficiency, but for analysis of nematode abundance and community composition in climate-change studies this is not a major problem. It is important to realise though that the extraction efficiency depends on the soil type; extracting nematodes from sandy soils is easier than from clay or organic soils (or humus). The final choice of the extraction method depends on the availability of facilities, costs of equipment, water use, and labour. Van Bezooijen (2006) and EPPO (2013) provide detailed comparisons of the costs and benefits of different nematode extraction methods.

Baermann funnels: One of the most commonly used methods for extraction of nematodes from soils is the use of Baermann funnels. This simple method makes use of the active movement of nematodes. Soil samples are wrapped in filter or tissue paper, or cheese cloth, and then placed into funnels filled with water and equipped with a piece of tubing at the stem, closed with a clamp. Instead of wrapping the sample in paper or cloth, the sample can also be spread out on a small sieve inserted into the funnel; the larger extraction surface increases the extraction efficiency. To further increase the extraction surface, the Baermann funnel method can be modified by using larger dishes (see, ‘Oostenbrink dish’ below) or trays where the soil sample can be spread in a thin layer. The nematodes will crawl out of the wet soils and then passively sink to the bottom of the funnel stem where they can be collected. The duration of the extraction depends on the soil type, the sample size, and the extraction surface, but typically 24–72 hours is sufficient. It is critical that the soil samples never dry out. Advantages of Baermann funnels (and derived tray methods) are their simplicity and low costs. Disadvantages are their low extraction efficiency for large samples and for immotile nematodes.

Oostenbrink elutriators: Another commonly used method for the extraction of free-living soil nematodes from soil, especially in larger nematode labs, is the use of Oostenbrink elutriators (Oostenbrink, 1960), particularly for larger soil samples. The method typically consists of two phases. The first phase makes use of differences in size, shape, and sedimentation rate between nematodes and soil particles, while the second phase makes use of nematode mobility (just like Baermann funnels). In the Oostenbrink elutriator (Fig. 4.10.3), an upward water stream makes the nematodes and fine soil particles float in the upper extraction column, whereas heavier soil particles settle in the lower part. The suspension in the extraction column is then let out and poured onto a set of four 45 μm sieves. In the second phase, the debris washed from the sieves can be further cleaned by the use of ‘Oostenbrink dishes’. These are plastic or stainless steel dishes with a cross piece and an extraction sieve equipped with milk filters (see EPPO, 2013 for an example). The dishes are generally incubated for ~48 hours at room temperature during which the nematodes move through the filters into the water in the dish. During incubation the filters must be kept moist at all times. Verschoor & De Goede (2000) give more information on the overall extraction efficacy and parameters influencing the extraction efficacy. Advantages of Oostenbrink elutriators are the generally high efficiency and standardisation of extractions. Major disadvantages are the high costs of the custom-made equipment, and the physical space needed for the permanent installation of the elutriators. This method is therefore only recommended for labs where nematodes are extracted on a more or less routine basis.

To note, methods based on nematode motility do not capture slow-moving and inactive nematodes, or eggs. The number of nematodes moving out of a soil sample further depends on extraction duration and sample type. The efficiency usually increases when the debris layer is thin. The water temperature also influences nematode motility in the soil sample and therefore the numbers of nematodes in the final suspension.

Centrifugal flotation: Free-living soil nematodes can be separated from soils by centrifugation because of the difference in specific gravity between nematodes and soil particles. Soil samples are suspended in a highly-concentrated sugar solution: based on specific gravity the nematodes float, while the soil particles sink. This so-called centrifugal flotation method can be used for all types of soil, but is more efficient for loose, sandy soils than for aggregated clay or loam soils. To handle larger samples and obtain higher extraction efficiency, pre-extraction of the sample is recommended to get a more concentrated soil suspension prior to centrifugation. Pre-extraction can be done with Oostenbrink elutriators (see above), for example, or with a simple sieving procedure (top: 180 µm; bottom: 38 µm or 32 µm). The actual separation method then consists of two centrifugation cycles. In the first cycle, the concentrated soil suspension is centrifuged so all particles with a specific gravity >1 precipitate; this includes the nematodes. The supernatant is then discarded. In the second cycle, concentrated sugar solution is added to the sediment from the first phase, and the sediment is brought into suspension. After centrifugation, the nematodes float in the supernatant, whereas the soil particles are precipitated to the bottom of the centrifugation tube. The supernatant is passed through a 25 mm sieve, after which the nematodes can be rinsed into a vial or tube. An advantage of the centrifugation method is that not only active nematodes but also slow-moving and inactive nematodes are extracted. More detailed directions for the centrifugal flotation method can be found in Jenkins (1964) and Van Bezooijen (2006). Another advantage of the centrifugal flotation method is that no special equipment is needed. The main piece of equipment is a standard table top centrifuge which can be found in most ecology and microbiology labs. Other than that, one needs a set of (portable) sieves and some standard labware and disposables. This means that this method can easily be applied at most universities and research institutes.

Extraction of nematodes from plant roots: Several methods have been developed for extraction of nematodes from roots (and other plant material), mostly in agricultural sciences. For analysis of nematodes from plant roots in terrestrial climate-change studies, Baermann funnels (see above) or a funnel spray apparatus (also known as ‘mist chamber’ or ‘mistifier’) are generally most suitable. Making use of nematode mobility and sedimentation rate, both these methods extract most active nematodes from roots. When root samples are moistened in water, nematodes crawl out and sink. The funnel spray apparatus consists of Baermann funnels equipped with small sieves, under a spray nozzle (Fig. 4.10.4). The washed roots are then placed in sieves with little legs which prevent the sieves from touching the water surface in the funnels. The nematodes will fall into the funnel where they settle. Nematodes should be collected from the funnels every day or two. The total duration of extraction depends on the type of root material and the nematode taxa, but typically 2–7 days is sufficient. Here, it is important to mention that part of the nematode population within plant roots is in the form of eggs which may hatch over time. If those numbers are of interest to the research question, samples need to be incubated for much longer, up to several weeks, allowing enough time for the eggs to hatch. Compared to normal Baermann funnels (as described above for soil samples), the funnel spray method yields nematodes in better condition, and the extraction efficiency is also higher. Cutting the roots into small pieces further enhances the extraction efficiency (Van Bezooijen, 2006). A disadvantage is that the funnel spray matter uses high amounts of water.

Fixation, preservation, and identification: Upon extraction from soils and/or plant roots, nematodes are collected as a clear suspension in water. For concentrating nematode suspensions for counting or fixation, the natural nematode sedimentation rate is used. The amount of fluid can be reduced by sieving the suspension, or by pipetting the liquid after the nematodes have settled. Nematodes can be counted and identified alive, or nematodes can be fixed and preserved and counted and identified at a later stage. Live nematodes can be kept alive and in good condition for several days when refrigerated at ± 4°C. Nematode identification, however, is easier done when the nematodes are dead and fixed. Usually the best results are obtained by killing the nematodes rapidly through heating (up to 65–90°C) followed by immediate fixing. With a hot fixative, these two steps can be combined. Cooling must happen fast, because an extended heating period causes deformations (Van Bezooijen, 2006). Formalin (4%) is most commonly used as a fixative. Note, that formalin is harmful to human health and therefore fixation work must be carried out in a fume hood. After fixation, nematodes can be transferred to other preservatives. Nematodes can be counted and/or identified to broad taxonomic groups (i.e. family level) in suspension using an inverted microscope. Alternatively, for higher taxonomic resolution (i.e. genus- or species-level), nematodes should be mounted on slides (see Van Bezooijen, 2006 for detailed instructions), and identified using a compound microscope. For ecological studies, typically all nematodes in the sample are counted after which a random subset (± 150–200 individuals) of the nematodes is identified. For inference on “function”, nematodes are then often allocated to feeding groups (see above).

Where to start

EPPO (2013), Van Bezooijen (2006)

Mesofauna extraction methods

The mesofauna should be extracted from the soil and litter immediately after sampling, but storage for a short time (1–2 weeks) at 4–5 °C is common when there are practical limitations to extraction capacity. This is unlikely to affect the overall extraction results. Extraction of mesofauna from soil cores can be done either by active or passive extraction. Active extraction relies on mesofauna migration towards a collection device in response to a stimulus, for example temperature or water availability, and is by far the most common extraction method used (Andre et al., 2002). Passive or mechanical extraction methods are more commonly used when sampling larger soil organisms, and rely on the physical separation of the fauna from the soil by hand-sorting, flotation, or chemical extraction.

For a critical review of different soil core extraction methods, including comparisons of efficiency and consequences for biodiversity estimates, see Andre et al. (2002).

Active mesofauna extraction methods

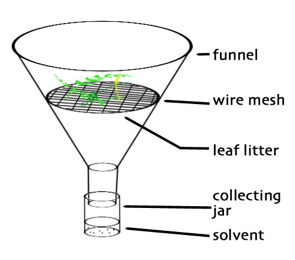

Heat and light extraction: Extracting mesofauna from soil cores by heat and light is the most common method for assessing springtails, mites, diplurans, and proturans. Heat extraction will also frequently extract earthworms, enchytraeids, bristletails, insect larva, and small adult insects and spiders, although other sampling methods are more suitable for these organisms (see protocol 4.11. Macroinvertebrate community composition). Heat and light extraction is often referred to as Berlese or Tullgren extraction, as the method was first developed and described by Berlese (1905) and Tullgren (1917). Later modifications to the extraction method have been described by MacFadyen (1961), Petersen (1978), and Andrén (1985). The principle of the method is to slowly heat and dry the soil sample from the top, while placing a collection beaker below, creating a temperature and moisture gradient which will induce movement of the mesofauna towards the collection beaker (Fig. 4.10.5). The set-up most commonly used today consists of a temperature-controlled top chamber, where heating elements (e.g. light bulbs) are used to create a set heating temperature, and a cooling chamber at the bottom (Fig. 4.10.6). Extraction temperature usually starts at room temperature and should be increased up to 60 °C over the course of about a week. Samples should be completely dry when extraction ends. Soil cores are placed inside the extraction chamber upside down, with the litter layer facing downwards, on top of a mesh to prevent soil particles from falling into the collection beaker below.

The collection beaker should contain a liquid for killing and preserving the animals, for example 70% ethanol, benzoic acid, propylene glycol, or ethylene glycol. The extraction method can also be used for collecting live specimens: the collection beaker should then be layered with a substrate to keep the extracted animals moist, such as moist plaster of Paris.

Moulting microarthropods as well as larval or nymphal stages of many prostigmatid mites are inactive and will not be extracted by heat. The mesh, on which the soil samples rest during extraction, might also discriminate against larger sized animals if the mesh size is small. The extraction apparatus also needs electricity for heating, which can be limiting in some places. An alternative using only drought has been described by Owen (1987). Mesh bags are filled with a soil/litter sample and placed inside an outer cloth bag. When the sample is left to dry out, the mesofauna will actively move out of the mesh bag and fall into a collection beaker in the bottom of the outer bag.

Wet extraction: O’Connor wet funnel extraction (O’Connor, 1955) is primarily used to extract enchytraeids from the soil. Here, the same principle of using a heating source to create a temperature gradient in the sample as for the Berlese-Tullgren method is used. A mesh or sieve is placed inside a water-filled funnel or a bowl, with room for the collection of animals below. The funnel or bowl is filled with tap water covering the mesh, and the soil sample is placed on the mesh so that it is completely soaked. Increasing the temperature gradually for 8–24 hours, the enchytraeids move away from the heat and towards the bottom of the funnel. By opening the funnel from below, or removing the mesh with the soil sample, the water with the live enchytraeids can be collected. The extraction method can also be used without heating if the extraction time is extended to several days. The enchytraeids should be collected daily if this method is used. Enchytraeids are best identified alive, preferably within 2 days after extraction. The water samples should be kept at 5–10 °C, and the water should be changed daily to avoid deoxygenation.

Passive mesofauna extraction methods

Hand sorting: Hand sorting of field soil samples may potentially recover all mesofauna, including non-mobile forms such as eggs and dormant or immobile stages. However, the method is laborious and time-consuming, and it is difficult to detect and collect the smaller microarthropods efficiently. It works best with loosely structured soil types without roots or clay aggregates. For a comparison of hand-sorting techniques and time restraints, see Schmidt (2001).

Flotation: Extraction by flotation relies on the hydrophobic properties of the cuticle of the organisms, or their specific gravity. The soil is suspended in water, and animals are collected from the water surface. This method can be useful when sampling loosely structured soil with few roots and clay particles, and with low organic content. Stirring or centrifuging the soil can increase the method’s efficiency. The method extracts inactive as well as active stages; however, only species with a hydrophobic cuticle will float on the water’s surface. Using a more dense solution such as brine or magnesium sulfate can extract all soil organisms with a specific gravity lower than the solution. The animals are then collected at the bottom of the fluid, and the samples will often have to be sieved or hand sorted after extraction by flotation. A detailed description of flotation devices and solutions is found in Edwards (1991).

Pitfall traps, sticky traps, and field sampling by hand

Larger, surface-dwelling mesofauna, especially large springtail and mite species, as well as bristletails, can be collected using similar methods as described for macroinvertebrate sampling (see protocol 4.11. Macroinvertebrate community composition). Pitfall traps or sticky traps will catch organisms moving actively around on the soil or litter surface. Collection of animals directly from the soil or litter surface can be efficient, but this method is less suitable for assessment of soil communities as there may be an overrepresentation of migrating or aggregating individuals. A brush, soft tweezers, or a pipette tip aspirator can be used to collect individuals by hand (Davidson & Broady, 1996; Sinclair & Sjursen, 2001).

Morphological identification

Identification of mesofauna is the most time-consuming part of the procedure and good taxonomic knowledge is needed. Species or family identification is usually done under a compound microscope, while coarse sorting and identification to functional groups can be carried out using a stereo microscope. Several identification keys to orders, families, and species exist: for springtails (Gisin, 1960; Fjellberg, 1998, 2007), mites (Balogh & Balogh, 1992; Krantz & Walter, 2009), and enchytraeids (Nielsen & Christensen, 1959; Schmelz & Collado, 2010).

Where to start

Andre et al. (2002), Edwards (1991), O’Connor (1955), Petersen (1978) {Andre, 2002 #893}

4.10.2 Special cases, emerging issues, and challenges

Genetic sequencing

Genetic sequencing or molecular barcoding techniques to identify soil microbial communities have been widely applied, but such techniques for characterising nematodes and soil mesofauna are still relatively new, and only recently have seen an increase in application. For nematodes, taxa abundances can be determined using quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) techniques. For analyses of the taxonomic and functional composition of soil nematode communities, molecular diversity analyses can be used, such as DGGE, T-RFLP, and high-throughput sequencing (HTS). qPCR may reveal lower abundances than traditional morphological approaches. On the other hand, HTS produces higher taxonomic resolution, while relative HTS and relative morphological nematode data show very strong correlations (Geisen et al., 2018). Therefore, a combination of molecular and morphological approaches would provide the most detailed characterisation of soil nematode community responses to climate change (Geisen et al., 2018). Interestingly, Geisen et al. (2018) also indicate that while material costs are higher for molecular methods compared to morphological methods, the reduction in labour costs easily offsets the extra costs when sample sizes increase. This would particularly be the case in high-income countries. For more details on the progress and application of molecular nematode analyses, and comparisons of traditional morphological approaches and new molecular approaches, we refer to Sapkota & Nicolaisen (2015), Geisen et al. (2018), and Wilschut et al. (2019). For mesofauna, Oliverio et al. (2018) compare traditional morphological identifications of heat-extracted soil arthropod families with DNA meta-barcoded heat-extracted arthropods and DNA meta-barcoded bulk soil. The results are strongly correlated. However, discrepancies due to the lack of arthropod species in the reference databases and due to the presence of DNA from fragments of dead specimens in the bulk soil were found, as well as specific primer biases.

4.10.3 References

Theory, significance, and large datasets

Andre et al. (2002), {Andre, 2002 #893}Bardgett (2002), Coleman & Whitman (2005), Coleman et al. (2018), Edwards (1991), Ferris et al. (2001)

More on methods and existing protocols

Andre et al. (2002), Edwards (1991), Geisen et al. (2018), ISO (2006, 2007a, 2007b, 2018), O’Connor (1955), Oliverio et al. (2018), Petersen (1978), Sapkota & Nicolaisen (2015), Yeates et al. (1993)

All references

Alatalo, J. M., Jagerbrand, A. K., & Cuchta, P. (2015). Collembola at three alpine subarctic sites resistant to twenty years of experimental warming. Scientific Reports, 5, 10.1038/srep18161.

Alatalo, J. M., Jaegerbrand, A. K., Juhanson, J., Michelsen, A., & Luptacik, P. (2017). Impacts of twenty years of experimental warming on soil carbon, nitrogen, moisture and soil mites across alpine/subarctic tundra communities. Scientific Reports, 7, 10.1038/srep44489.

Andre, H. M., Ducarme, X., & Lebrun, P. (2002). Soil biodiversity: myth, reality or conning? Oikos, 96(1), 3-24.

Andrén, O. (1985). Microcomputer-controlled extractor for soil microarthropods. Soil Biology & Biochemistry, 17(1), 27-30.

Balogh, J., & Balogh, P. (1992). The Oribatid Mites Genera of the World. Budapest: Hungarian Natural History Museum.

Bardgett, R. D. (2002). Causes and consequences of biological diversity in soil. Zoology, 105(4), 367-374.

Bardgett, R. D., & Cook, R. (1998). Functional aspects of soil animal diversity in agricultural grasslands. Applied Soil Ecology, 10(3), 263-276.

Bardgett, R. D., Cook, R., Yeates, G. W., & Denton, C. S. (1999). The influence of nematodes on belowground processes in grassland ecosystems. Plant and Soil, 212, 23-33.

Bedano, J. C., Cantú, M. P., & Doucet, M. E. (2006). Influence of three different land management practices on soil mite (Arachnida: Acari) densities in relation to a natural soil. Applied Soil Ecology, 32(3), 293-304.

Berlese, A. (1905). Apparecchio per raccogliere presto e in gran numero piccoli arthropodi. Redia, 2, 85-90.

Chen, B., Snider, R. J., & Snider, R. M. (1995). Food preference and effects of food type on the life history of some soil Collembola. Pedobiologia, 39, 496–505.

Coleman, D. C., & Whitman, W. B. (2005). Linking species richness, biodiversity and ecosystem function in soil systems. Pedobiologia, 49(6), 479-497.

Coleman, D. C., Callaham, M. A., & Crossley, D. A. (2018). Fundamentals of Soil Ecology (3rd edition). Academic Press.

Cortet, J., Joffre, R., Elmholt, S., & Krogh, P. H. (2003). Increasing species and trophic diversity of mesofauna affects fungal biomass, mesofauna community structure and organic matter decomposition processes. Biology and Fertility of Soils, 37(5), 302-312.

Davidson, M. M., & Broady, P. A. (1996). Analysis of gut contents of Gomphiocephalus hodgsoni Carpenter (Collembola: Hypogastruridae) at Cape Geology, Antarctica. Polar Biology, 16(7), 463-467.

De Long, J. R., Dorrepaal, E., Kardol, P., Nilsson, M.-C., Teuber, L. M., & Wardle, D. A. (2016). Contrasting responses of soil microbial and nematode communities to warming and plant functional group removal across a post-fire boreal forest successional gradient. Ecosystems, 19, 339-355.

Edwards, C. A. (1991). The assessment of populations of soil-inhabiting invertebrates. Agriculture Ecosystems & Environment, 34(1-4), 145-176.

Elmendorf, S. C., Henry, G. H. R., Hollister, R. D., Bjork, R. G., Bjorkman, A. D., Callaghan, T. V., … Wookey, P. A. (2012). Global assessment of experimental climate warming on tundra vegetation: heterogeneity over space and time. Ecology Letters, 15(2), 164-175.

EPPO European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization (2013). PM 7/119 (1) Nematode extraction. EPPO Bulletin, 43, 471-495.

Ferris, H., Bongers, T. & De Goede, R. G. M. (2001). A framework for soil food web diagnostics: extension of the nematode faunal analysis concept. Applied Soil Ecology, 18, 13-29.

Fjellberg, A. (1998). The Collembola of Fennoscandia and Denmark: Part I: Poduromorpha. Fauna Entomologica Scandinavica, 35, 1-184.

Fjellberg, A. (2007). The Collembola of Fennoscandia and Denmark: Part II: Entomobryomorpha and Symphypleona. Fauna Entomologica Scandinavica, 42, 1-266.

Geisen, S., Snoek, L. B., ten Hooven, F. C., Duyts, H., Kostenko, O., Bloem, J., … van der Putten, W. H. (2018). Integrating quantitative morphological and qualitative molecular methods to analyse soil nematode community responses to plant range expansion. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 9, 1366-1378.

Gisin, H. (1960). Collembolenfauna Europas. Genève: Museum d’Histoire Naturelle.

Hedlund, K., & Sjögren-Öhrn, M. (2000). Tritrophic interactions in a soil community enhance decomposition rates. Oikos 88(3), 585-591.

Hopkin, S. P. (1997) Biology of the Springtails (Insecta: Collembola). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hågvar, S., & Klanderud, K. (2009). Effect of simulated environmental change on alpine soil arthropods. Global Change Biology 15(12), 2972-2980.

ISO (2006). Soil quality – Sampling of soil invertebrates – Part 2. In Sampling and extraction of micro-arthropods (Collembola and Acarina) (Vol. ISO 23611-2:2006).

ISO (2007a). Soil quality – Sampling of soil invertebrates – Part 3. In Sampling and soil extraction of enchytraeids (Vol. ISO 23611-3:2007).

ISO (2007b). Soil quality – Sampling of soil invertebrates – Part 4. In Sampling, extraction and identification of soil-inhabiting nematodes (Vol. ISO 23611-4:2007).

ISO (2018). Soil quality – Sampling of soil invertebrates – Part 1. In Hand-sorting and extraction of earthworms (Vol. ISO 23611-1:2018).

Jenkins, W. R. (1964). A rapid centrifugal-flotation technique for separating nematodes from soil. Plant Disease Report 48(9), 692.

Kardol, P., Cregger, M. A., Campany, C. E., & Classen A. T. (2010). Soil ecosystem functioning under climate change: plant species and community effects. Ecology, 91(3), 767-781.

Konestabo, H. S., Michelsen, A., & Holmstrup, M. (2007). Responses of springtail and mite populations to prolonged periods of soil freeze-thaw cycles in a sub-arctic ecosystem. Applied Soil Ecology, 36(2-3), 136-146.

Krab, E. J., Cornelissen, J. H. C., & Berg, M. P. (2015). A simple experimental set-up to disentangle the effects of altered temperature and moisture regimes on soil organisms. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 6(10), 1159-1168.

Krantz, G. W., & Walter, D. E. (Eds.) (2009). A Manual of Acarology (3rd edition). Texas: Texas Tech University Press.

Leinaas, H. P., Bengtsson, J., Janion-Scheepers, C., Chown, S. L. (2015). Indirect effects of habitat disturbance on invasion: nutritious litter from a grazing resistant plant favors alien over native Collembola. Ecology and Evolution, 5(16), 3462-3471.

Macfadyen, A. (1961). Improved funnel-type extractors for soil arthropods. Journal of Animal Ecology, 30(1), 171-184.

Mebes, K., & Filser, J. (1998). Does the species composition of Collembola affect nitrogen turnover? Applied Soil Ecology, 9(1-3), 241–247.

Nielsen, C. O., & Christensen, B. (1959). The Enchytraeidae. Critical revision and taxonomy of European species. (Studies on Enchytraeidae VII). Natura Jutlandica, 8-9, 1-160.

O’Connor, F. B. (1955). Extraction of enchytraeid worms from a coniferous forest soil. Nature, 175, 815-816.

Ojala, R., & Huhta, V. (2001). Dispersal of microarthropods in forest soil. Pedobiologia, 45(5), 443-450.

Oliverio, A. M., Gan, H. J., Wickings, K., & Fierer, N. (2018). A DNA metabarcoding approach to characterize soil arthropod communities. Soil Biology & Biochemistry, 125, 37-43.

Oostenbrink, M. (1960). Estimating nematode populations by some selected methods. In J. N. Sasser, & W. R. Jekins (eds.), Nematology (pp. 85-102). Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press.

Owen, J. A. (1987). The ‘Winkler extractor’. Proceedings and Transactions of the British Entomological and Natural History Society, 20(4), 129-132.

Petersen, H. (1978). Some properties of two high-gradient extractors for soil microarthropods, and an attempt to evaluate their extraction efficiency. Natura Jutlandica, 20, 55-122.

Santos, P. F., Phillips, J., & Whitford, W. G. (1981). The role of mites and nematodes in early stages of buried litter decomposition in a desert. Ecology 62(3), 664-669.

Sapkota, R., & Nicolaisen, M. (2015). High-throughput sequencing of nematode communities from total soil DNA extractions. BMC Ecology, 15, 1-8.

Schmelz, R. M., & Collado, R. (2010). A guide to European terrestrial and freshwater species of Enchytraeidae (Oligochaeta). Soil Organisms, 82(1), 1-176.

Schmidt, O. (2001). Time-limited soil sorting for long-term monitoring of earthworm populations. Pedobiologia, 45(1), 69-83.

Setälä, H., Tyynismaa, M., Martikainen, E., & Huhta, V. (1991). Mineralization of C, N and P in relation to decomposer community structure in coniferous forest soil. Pedobiologia, 35, 285-316.

Setälä, H., Laakso, J., Mikola, J., & Huhta, V. (1998). Functional diversity of decomposer organisms in relation to primary production. Applied Soil Ecology, 9(1-3), 25-31

Sinclair, B. J., & Sjursen, H. (2001). Terrestrial invertebrate abundance across a habitat transect in Keble Valley, Ross Island, Antarctica. Pedobiologia, 45(2), 134-145.

Sjursen, H., Michelsen, A., & Jonasson, S. (2005). Effects of long-term soil warming and fertilisation on microarthropod abundances in three sub-arctic ecosystems. Applied Soil Ecology, 30(3), 148-161.

Tullgren, A. (1917). En enkel apparat för automatiskt vittjande av sållgods. Entomologisk Tidskrift, 38, 97-100.

Van Bezooijen, J. (2006). Methods and techniques for Nematology. Script, 112 p. https://www.wur.nl/upload_mm/f/9/3/10aac0cb-8289-400a-a6e5-c4687461d138_MethodsandTechniquesforNematology.pdf [accessed on 15 May 2019].

Van den Hoogen, J., Geisen, S., Routh, D., Ferris, H., Traunspurger, W., Wardle, … & Bardgett, R.D. (2019). Soil nematode abundance and functional group composition at a global scale. Nature, 1.

Verhoef, H. A., Prast, J. E., & Verweij, R. A. (1988). Relative importance of fungi and algae in the diet and nitrogen nutrition of Orchesella cincta (L.) and Tomocerus minor (Lubbock) (Collembola). Functional Ecology, 2(2), 195-201.

Verschoor, B. C., & De Goede, R. G. M. (2000). The nematode extraction efficiency of the Oostenbrink elutriator-cottonwool filter method with special reference to nematode body size and life strategy. Nematology, 2, 325–342.

Wilschut, R. A., Geisen, S., Martens, H., Kostenko, O., de Hollander, M., ten Hooven, F. C., … van der Putten, W. H. (2019). Latitudinal variation in soil nematode communities under climate warming‐related range‐expanding and native plants. Global Change Biology, DOI: 10.1111/gcb.14657

Yeates, G. W., Bongers, T., De Goede, R. G. M., Freckman, D. W., & Georgieva, S. S. (1993). Feeding-habits in soil nematode families and genera – an outline for soil ecologists. Journal of Nematology 25(3), 315-331.

Authors: Konestabo HS1 & Kardol P2

Reviewer: Birkemoe T3

Affiliations

1 The Science Library, University of Oslo, Norway

2 Department of Forest Ecology and Management, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, 901-83 Umeå, Sweden

3 Faculty of Environmental Sciences and Natural Resource Management, Norwegian University of Life Sciences, Ås, Norway