Authors: Malyshev AV1

Reviewers: Muffler L1,2, Wilfahrt P3

Measurement unit: days to budburst, proportion of budburst; Measurement scale: plot; Equipment costs: €; Running costs: €; Installation effort: low; Maintenance effort: medium to high; Knowledge need: low; Measurement mode: manual

Vegetative bud dormancy is a characteristic of many northern plant species describing a requisite cold period for budburst to occur in spring (Harrington et al., 2010). Tracking changes in bud dormancy depth allows the determination of the required temperature sums needed for budburst, thereby increasing the mechanistic understanding of subsequent phenology changes (Laube et al., 2014; Olsen, 2014; Pagter et al., 2015). Artificial warming is necessary to quantify bud dormancy depth and, when combined with photoperiod manipulation, can also be used to separate effects of photoperiod-sensitivity in certain species (Basler & Körner, 2012; Way & Montgomery, 2014; Malyshev et al., 2018). The effect of increased temperatures on bud dormancy depth depends on seasonality of warming and may increase or decrease bud dormancy depth, which may delay or advance budburst, respectively (Kalcsits et al., 2009; Pagter et al., 2015). Temperature-mediated bud dormancy changes have been incorporated into bud phenology models (Kobayashi & Fuchigami, 1983; Schaber & Badeck, 2003; Harrington et al., 2010; Schmitz et al., 2014; Harrington & Gould, 2015) and can lead to better accuracy in predicting spring budburst. Growing season changes can, in turn, be better projected, leading to better estimates of changes in primary productivity. The influence of any environmental factor on bud dormancy state can be measured with this method, taking samples from a group of studied plants growing under different conditions.

4.4.1 What and how to measure?

Bud dormancy state and depth can be quantified via destructive measurements across time. Buds gradually enter the endo-dormant stage from late summer to autumn (timing is species-specific) where dormancy “depth” increases and this inhibition is later broken by species-specific periods of cold temperature (Sogaard et al., 2008). Only after this internal inhibition is broken will buds enter eco-dormancy where budburst is advanced by warming temperatures, although warm temperatures occuring during endo-dormancy may affect budburst, at least in some species (Harrington & Gould, 2015). Therefore, environmental factors may increase or decrease bud dormancy depth and in turn spring phenology depending on the timing of events or manipulations and studied species. In addition to the destructive bud dormancy measurements, spring plant phenology can also be recorded on individual plants (see protocol 4.5 Aboveground plant phenology) to predict species- or community level spring bud burst.

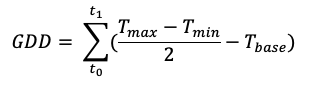

Dormancy state and depth is estimated from the percentage of buds that burst and the mean time required for each bud to burst under optimal growing conditions. Such conditions are termed forcing requirements, where a temperature of approximately 20 °C (Dennis, 2003; Cooke et al., 2012) and a photoperiod of 16 hours (Balandier et al., 1993; Harrington et al., 2010; Junttila & Hanninen, 2012) are considered optimal. Dormancy depth is quantified by the amount of time required for budburst to occur under forcing conditions: the shorter the forcing period, the lower the bud dormancy depth. Although breaking of endo-dormancy is a gradual and continuous process, more than 50% budburst is generally considered as the point at which bud dormancy is broken (Welling et al., 2004; Anzanello et al., 2014). Forcing requirements should be expressed in a standardised way as temperatures vary constantly; growing degree days (GDD) can standardise this variation and is calculated as:

where t0 is the starting day of the warming period, t1 is the day at which budburst is observed, Tmax and Tmin are daily maximum and minimum air temperature, respectively, and Tbase is a constant representing a minimum temperature threshold required for budburst activity (often set at 5 ˚C; Polgar & Primack, 2011). Fu et al. (2016) additionally provide functions to calculate growing degree forcing units that capture non-linear accumulation of forcing units.

It is also useful to quantify bud dormancy at two different day lengths (8 h and 16 h are suggested) for each plant group at each sampling date to establish the sensitivity of bud dormancy to photoperiod, which can reveal non-linear responses to warming (Malyshev et al., 2018).

Where to start

Balandier et al. (1993), Champagnat (1989), Dennis (2003), Primack et al. (2015)

Method selection and sample size

Bud dormancy depth can be tested anytime after the terminal buds for next years’ growth, have formed, which usually happens between August and September. Leaves, if present, are removed from plants, or twig cuttings as described below, prior to measuring dormancy depth. For small tree seedlings the best method to test bud dormancy depth involves using whole plants, while for adult trees, twig cuttings provide a reliable substitute (Primack et al., 2015). A minimum of five potted tree seedlings per treatment per species/ecotype are suggested, although ten replicates are preferable. Tree seedlings are transferred to a greenhouse or climate chamber set at the above-mentioned forcing conditions. The percentage of budburst is recorded on each tree seedling every two days until 100 % budburst occurs or no further buds burst for four weeks. Total percentage of budburst, rate of budburst (time to reach 50 % budburst), and mean forcing requirement are recorded as parameters used to gauge dormancy depth. Budburst and leaf out are detected with the appearance of the first distinguishable leaf tip and when a leaf has unfolded, respectively (Li et al., 2003; Basler & Körner, 2014; Fu et al., 2014; Vitasse et al., 2014).

Two main methods exist for making twig cuttings of the plants: 1) whole twigs are cut 20–30 cm in length (Primack et al., 2015 and references therein) and 2) single node cuttings are cut, having only one lateral bud, with cuts approximately 3–5 cm below and 1 cm above the bud (Champagnat, 1989; Sønsteby & Heide, 2014). Ten replicates of twig cuttings from at least three different individuals per species are suggested. Method 1 is preferable to mimic field conditions as closely as possible if time is not an issue (up to 3 months for species developing deep dormancy), and gives a more realistic estimation of dormancy depth. Method 1 is also advised when leaf development is to be observed to completion (compared to timing of budburst alone) as the smaller twig segments in Method 2 may contain insufficient resources (e.g. sugars) for prolonged leaf growth. Method 2 is used when only relative (across treatments) warming-induced changes in bud dormancy over time is of primary interest (Boyer & South, 1989; Champagnat, 1989; Sønsteby & Heide, 2014).

Twig-cutting preparation

The length and diameter of twig cuttings should be kept similar across species to ensure similar resources available for budburst and leaf unfolding. The use of previous years’ shoots is suggested to standardise the ages of buds tested. All twig cuttings are placed in deionised water either in large containers containing several twigs (Method 1) or inserted into foam/plastic pads floating on water (Sønsteby & Heide, 2014; Method 2). Deionised water should be used to standardise trials and twigs should be treated with a disinfectant to prevent mould growth during the incubation period (Basler & Körner, 2012; Laube et al., 2014). The water must be changed twice a week and the twigs need to be recut at least weekly to ensure sufficient water uptake by the cuttings, each time cutting off 0.5–1 cm from the stem base. Measured parameters mirror those used for whole tree seedlings.

4.4.2 Emerging issues, methods, and challenges

Changes in the timing of transition between bud dormancy states and their depths as a result of climate change will need to be studied to explain the underlying mechanism driving changes in leaf phenology. The main challenge in bud dormancy quantification is in reducing the time required to determine the bud dormancy depth at a particular point in time. Bud dormancy depth can potentially be estimated faster at the expense of being less comparable among plant groups. Here, cell division activity of leaf primordia (Cooke et al., 2012) and concentrations of specific hormones and sugars (Li et al., 2003; Chao et al., 2007; Basler & Körner, 2014) can be analysed from collected bud/twig samples. Furthermore, genetic, epigenetic, and physiological changes have been documented during changes in bud dormancy (Rios et al., 2014). Extensive preliminary analyses are required to establish precise grading of cell division in different species, with potentially species-specific genetic, hormonal, and physiological changes driving bud dormancy. Whether key compounds such as abscisic acid (Giraudat et al., 1994) are directly related to the dormancy depth across species is unknown but the search for them could be useful to enable faster quantification of bud dormancy depth.

4.4.3 References

Theory, significance, and large datasets

Champagnat (1989), Chao et al. (2007), Cooke et al. (2012), Harrington & Gould (2015)

A database on bud dormancy depth of a large selection of species is available for download from: https://hdl.handle.net/10355/53250

More on methods and existing protocols

Dennis (2003), Junttila & Hanninen (2012), Malyshev et al. (2018), Sønsteby & Heide (2014), Vitasse et al. (2014)

All references

Anzanello, R., Fialho, F. B., dos Santos, H. P., Bergamaschi, H., & Marodin, G. A. B. (2014). Bud dormancy in apple trees after thermal fluctuations. Pesquisa Agropecuária Brasileira, 49, 457-464.

Balandier, P., Gendraud, M., Rageau, R., Bonhomme, M., Richard, J. P., & Parisot, E. (1993). Bud break delay on single node cuttings and bud capacity for nucleotide accumulation as parameters for endo- and paradormancy in peach trees in a tropical climate. Scientia Horticulturae, 55, 249-261.

Basler, D., & Körner, C. (2012). Photoperiod sensitivity of bud burst in 14 temperate forest tree species. Agriculture and Forest Meteorology, 165, 73-81.

Basler, D., & Körner, C. (2014). Photoperiod and temperature responses of bud swelling and bud burst in four temperate forest tree species. Tree Physiology, 34, 377-388.

Boyer, J. N., & South, D. B. (1989). Seasonal changes in intensity of bud dormancy in loblolly pine seedlings. Tree Physiology, 5, 379-385.

Champagnat, P. (1989). Rest and activity in vegetative buds of trees. Annals of Forest Science, 46, 9-26.

Chao, W. S., Foley, M. E., Horvath, D. P., & Anderson, J. V. (2007). Signals regulating dormancy in vegetative buds. International Journal of Plant Developmental Biology, 1, 49-56.

Cooke, J. E. K., Eriksson, M. E., & Junttila, O. (2012). The dynamic nature of bud dormancy in trees: Environmental control and molecular mechanisms. Plant, Cell & Environment, 35, 1707-1728.

Dennis, F. G. (2003). Problems in standardizing methods for evaluating the chilling requirements for the breaking of dormancy in buds of woody plants. Hort Science, 38(3), 347-350.

Fu, Y. S. H., Campioli, M., Vitasse, Y., De Boeck, H.J., Van den Berge, J., AbdElgawad, H., … Janssens, I. A. (2014). Variation in leaf flushing date influences autumnal senescence and next year’s flushing date in two temperate tree species. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 111, 7355-7360.

Fu, Y. S. H., Liu, Y., De Boeck, H. J., Menzel, A., Nijs, I., Peaucelle, M., … Janssens, I. A. (2016). Three times greater weight of daytime than of night-time temperature on leaf unfolding phenology in temperate trees. New Phytologist, 212, 590-597.

Giraudat, J., Parcy, F., Bertauche, N., Gosti, F., Leung, J., Morris, P. C., … Vartanian, N. (1994). Current advances in abscisic acid action and signalling. Plant Molecular Biology, 26, 1557-1577.

Harrington, C. A., & Gould, P. J. (2015). Tradeoffs between chilling and forcing in satisfying dormancy requirements for Pacific Northwest tree species. Frontiers in Plant Science, 6, 1-12.

Harrington, C. A., Gould, P. J., & St. Clair, J. B. (2010). Modeling the effects of winter environment on dormancy release of Douglas fir. Forest Ecology and Management, 259, 798-808.

Junttila, O., & Hanninen, H. (2012). The minimum temperature for budburst in Betula depends on the state of dormancy. Tree Physiology, 32, 337–345.

Kalcsits, L. A., Silim, S., & Tanino, K. (2009). Warm temperature accelerates short photoperiod-induced growth cessation and dormancy induction in hybrid poplar. Trees – Structure and Function, 23(5), 971-979.

Kobayashi, K. D., & Fuchigami, L. H. (1983). Modeling bud development during the quiescent phase in red-osier dogwood (Cornus sericea L.). Agricultural Meteorology, 28(1), 75-84.

Laube, J., Sparks, T. H., Estrella, N., Höfler, J., Ankerst, D. P., & Menzel, A. (2014). Chilling outweighs photoperiod in preventing precocious spring development. Global Change Biology, 20, 170-182.

Li, C. Y., Junttila, O., Ernstsen, A., Heino, P., & Palva, E. T. (2003). Photoperiodic control of growth, cold acclimation and dormancy development in silver birch (Betula pendula) ecotypes. Physiologia Plantarum, 117, 206-212.

Malyshev, A. V., Henry, H. A. L., Bolte, A., Arfin Khan, M. A. S., & Kreyling, J. (2018). Temporal photoperiod sensitivity and forcing requirements for budburst in temperate tree seedlings. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology, 248, 82-90.

Olsen, J. E. (2014). Effect of alternating day and night temperature on short day-induced bud set and subsequent bud burst in long days in Norway spruce. Frontiers in Plant Science, 5, art691.

Pagter, M., Andersen, U. B., & Andersen, L. (2015). Winter warming delays dormancy release, advances budburst, alters carbohydrate metabolism and reduces yield in a temperate shrub. AoB Plants, 7, plv024.

Polgar, C. A., & Primack, R. B. (2011). Leaf-out phenology of temperate woody plants: from trees to ecosystems. New Phytologist, 191, 926-941.

Primack, R. B., Laube, J., Gallinat, A. S., & Menzel, A. (2015). From observations to experiments in phenology research: investigating climate change impacts on trees and shrubs using dormant twigs. Annals of Botany, 116(6), 889-897.

Rios, G., Leida, C., Conejero, A., & Badenes, M. L. (2014). Epigenetic regulation of bud dormancy events in perennial plants. Frontiers in Plant Science, 5, art247.

Schaber, J., & Badeck, F.-W. W. (2003). Physiology-based phenology models for forest tree species in Germany. International Journal of Biometeorology, 47, 193-201.

Schmitz, J. D., Guédon, Y., Herter, F. G., Leite, G. B., & Lauri, P. É. (2014). Exploring bud dormancy completion with a combined architectural and phenological analysis: The case of apple trees in contrasting winter temperature conditions. American Journal of Botany, 101, 398-407.

Sogaard, G., Johnsen, O., Nilsen, J., & Junttila, O. (2008). Climatic control of bud burst in young seedlings of nine provenances of Norway spruce. Tree Physiology, 28, 311-320.

Sønsteby, A., & Heide, O. M. (2014). Chilling requirements of contrasting black currant (Ribes nigrum L.) cultivars and the induction of secondary bud dormancy. Scientia Horticulturae, 179, 256-265.

Vitasse, Y., Basler, D., & Way, D. (2014). Is the use of cuttings a good proxy to explore phenological responses of temperate forests in warming and photoperiod experiments? Tree Physiology, 34, 174-183.

Way, D. A., & Montgomery, R. A. (2014). Photoperiod constraints on tree phenology, performance and migration in a warming world. Plant, Cell & Environment, 38(9), 1725-1736.

Welling, A., Rinne, P., Viherä-Aarnio, A., Kontunen-Soppela, S., Heino, P., & Palva, E. T. (2004). Photoperiod and temperature differentially regulate the expression of two dehydrin genes during overwintering of birch (Betula pubescens Ehrh.). Journal of Experimental Botany, 55, 507-516.

Authors: Malyshev AV1

Reviewers: Muffler L1,2, Wilfahrt P3

Affiliations

1 Experimental Plant Ecology, Institute of Botany and Landscape Ecology, University of Greifswald, Greifswald, Germany

2 Plant Ecology, Albrecht-von-Haller Institute for Plant Sciences, University of Goettingen, Goettingen, Germany

3 Department of Disturbance Ecology, BayCEER, University of Bayreuth, Bayreuth, Germany