Authors: Michaletz ST1,2,3, Blonder B4,5

Reviewer: Prentice IC6

Measurement unit: various (see below); Measurement scale: leaf; Equipment costs: €€-€€€; Running costs: €-€€€; Installation effort: medium to high; Maintenance effort: -; Knowledge need: medium; Measurement mode: manual

Leaf thermal traits determine the exchanges of energy between leaves and their environment (Gates, 1980; Campbell & Norman, 1998; Monteith & Unsworth, 2013; Jones, 2014). As such, they are closely linked to leaf temperature, water loss, and carbon gain. Thermal properties that influence leaf energy fluxes include absorptance, angle, area (projected and total), emissivity, stomatal conductance, and width. Others are implicated in energy storage, and include mass, specific heat capacity, thickness, and water content (1-LDMC, leaf dry matter content; g g-1). Finally, composite leaf properties may influence both fluxes and storage, and include the leaf mass per area (LMA; kg m‑2) and the thermal time constant. Together these properties interact with microclimate variables to determine the energy balance and temperature of the leaf, with implications for physiological rates and plant-environment fluxes.

Each leaf trait plays a role in regulating leaf-environment energy fluxes. Absorptance quantifies the fraction of incident radiation that is not reflected or transmitted by the leaf. Angle determines how a leaf interchanges radiation with its environment. Area determines the amount of leaf surface that contributes to radiation, convection, and latent heat (transpiration) fluxes. Emissivity quantifies the leaf’s ability to emit thermal radiation. Stomatal conductance determines the instantaneous rate of evaporation of water through stomatal pores, which influences latent heat fluxes. Width partially determines the depth of the leaf boundary layer, which in turn influences rates of transpiration and convection. Mass, specific heat capacity, thickness, and water content determine how much thermal energy a leaf can store. LMA relates the amount of mass that can store thermal energy to the surface area over which energy can flow between the leaf and environment. The thermal time constant quantifies how rapidly leaf temperature responds to temporal variations in microclimate; small thermal time constants correspond to leaves that respond rapidly to changes in environmental temperature, while large thermal time constants correspond to leaves that respond slowly to changes in environmental temperature. Because each thermal trait helps regulate leaf energetics, metabolism, and physiology, they all play critical roles in linking environmental variation to plant function.

Leaf thermal traits are key variables for understanding and predicting the effects of climate and global change on vegetation. They vary across environmental gradients, which may reflect acclimation and local adaptation that maximise plant performance and ultimately fitness. For example, leaf thermal traits can decouple leaf temperature from ambient air temperature, resulting in a relative homeostasis that helps maintain leaf temperatures near metabolic optima (Michaletz et al., 2015, 2016; Dong et al., 2017). Thermal traits such as leaf angle and absorptance have been shown to vary directionally across elevational temperature gradients (Ehleringer, 1988). Variation in these and other traits may underlie the relative invariance of carbon gain across environmental gradients that has been observed in many studies (Körner & Diemer, 1987; Diemer & Körner, 1996; Enquist et al., 2017; Malhi et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2017; Michaletz, 2018).

Leaf thermal traits may also minimise temporal variation in leaf temperatures and physiological rates. For example, the thermal time constant controls temporal variation in leaf temperature, which in turn influences instantaneous and time-integrated leaf carbon gain (Berry & Bjorkman, 1980; Yamori et al., 2014; Michaletz et al., 2015, 2016) and, ultimately, ecosystem carbon fluxes. Large time constants may dampen leaf temperature variation relative to ambient levels and help maintain leaves near metabolic optima (Michaletz et al., 2015, 2016), while small time constants may allow stronger atmospheric coupling and dissipation of heat. Leaf thermal traits thus play an important role in how ecosystem fluxes of water, gases, and energy vary across climate gradients and respond to global change.

Although the importance of leaf thermal traits in controlling leaf temperatures and physiological rates is well established, variation of leaf thermal traits in response to environmental variation has been understudied relative to leaf economic traits. Characterising variation in leaf thermal traits across climate gradients and in response to climate change, and understanding the implications of this variation for leaf energetics and metabolism, is a frontier research area in global change biology.

5.6.1 What and how to measure?

Leaf thermal traits vary substantially in both time and space. Studies have characterised variation through leaf ontogeny and season (Wu et al., 2016, 2017) or within individual plant crowns (Sack et al., 2006; Hulshof & Swenson, 2010). Other studies aim to minimise this variation by preferentially targeting young, fully-expanded leaves from sunlit areas of the canopy (Pérez-Harguindeguy et al., 2013). Thus, sampling schemes used to address multiple scales of variation in leaf properties are recommended. For example, sampling should generally aim for at least 5 leaves (leaflets) per individual, from 5 individuals per species, in order to have robust estimates of the mean (Baraloto et al., 2010; Hulshof & Swenson, 2010). Measurements should be paired at the leaf scale when estimating composite traits such as LMA, LDMC, or the thermal time constant (Knight & Ackerly, 2003; Keenan & Niinemets, 2016; Michaletz et al., 2016). We refer readers to Baraloto et al. (2010) and Hulshof & Swenson (2010) for further information on leaf trait sampling design.

Some thermal traits (e.g. angle and stomatal conductance) require in situ measurement on the intact live plant, while other thermal traits require destructive sampling and laboratory measurement. Thus, traits should be measured in a specific sequence: angle, stomatal conductance, absorptance, emissivity, fresh mass, area and width, dry mass, and specific heat capacity. Destructively sampled leaves should be stored in plastic zipper bags in a refrigerator or under ice until all measurements have been obtained. Measurements can then be used to calculate composite traits such as LMA, LDMC, and the thermal time constant. These recommendations are intended to help minimise the effects of sampling and measurement protocols on the measured variables (e.g. resulting from xylem embolism, evaporation, leaf shrinkage, etc.)

The angle (rad) of an individual leaf can be measured using a clinometer. The leaf angle is measured as the angle between the horizontal plane (ground) and a plane parallel to the leaf blade. Design of leaf angle measurements should consider that angle can vary diurnally or seasonally in response to plant water status and leaf turgor.

Stomatal conductance (mol m-2 s-1) can be measured using a leaf porometer or a gas exchange system (see protocol 5.7 Stomatal conductance). Many studies measure the maximum stomatal conductance of well-watered plants under in situ light and growth conditions (e.g. mid-morning measurements), although stomatal conductance varies widely through time and thus measurement strategies will vary depending on the research question. Stomatal conductance is generally measured in molar units, but energy balance analyses sometimes require velocity units; velocity units can be calculated from molar units as gs,v = gs,m(RT/P), where gs,v (m s-1) is stomatal conductance in velocity units, gs,m (mol m-2 s-1) is stomatal conductance in molar units, R (8.3145 Pa m-3 mol-1 K-1) is the gas constant, T (K) is air temperature, and P (Pa) is air pressure (Jones, 2014).

Absorptance (dimensionless) is measured using a spectroradiometer with an integrating sphere (Ehleringer, 1981; Shiklomanov et al., 2016). Absorptance should be measured across the total solar wavelengths 400–3000 nm, as the full spectrum is relevant for leaf radiation fluxes (Ehleringer, 2000). Absorptance can alternatively be measured across a smaller range of wavelengths (e.g. 400–700 nm) and corrected to the 400–3000 nm region using calibration relationships established for the region and taxa of interest (Ehleringer, 1981). If an integrating sphere is not available, absorptance can be estimated from spectroradiometer reflectance spectra and inversion of the PROSPECT-5B leaf radiative transfer model (Shiklomanov et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2018).

Emissivity (dimensionless) can be measured using a thermocouple and infrared temperature sensor with an adjustable emissivity setting. The infrared sensor emissivity is adjusted and taken as the value where the temperature estimated from the infrared sensor agrees with that of a fine thermocouple affixed to the leaf surface (see protocol 5.5 Leaf temperature; ASTM Standard E1933-14, 2014).

Measurement protocols for leaf area (m2), leaf width (m), water-saturated fresh mass (kg), dry mass (kg), LDMC (dimensionless), and LMA (kg m-3) are described in Pérez-Harguindeguy et al. (2013) (see also protocol 4.16 Functional traits). The specific heat capacity c (J kg-1 K-1) varies with leaf water content (1 – LDMC) and can be calculated using the rule of simple mixtures (Michaletz et al., 2015):

![]()

where cw (4180 J kg-1 K-1) is the specific heat capacity of water. The specific heat capacity of leaf dry matter cLDM (J kg-1 K-1) can be measured on oven-dried leaf samples using differential scanning calorimetry (DSC; ASTM Standard E1269-11, 2011). If a thermogravimetric analyser is unavailable for DSC, a value of cLDM = 1500 J kg-1 K-1 can be assumed (Ahn et al., 2009; Zanoelo et al., 2011; Dupont et al., 2014).

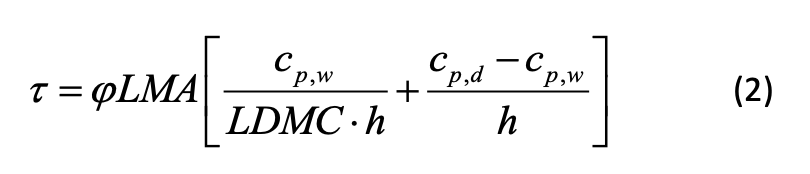

The leaf thermal time constant τ (s) can be quantified in two ways. First, it can be quantified via measurement of leaf temperature time series data (see protocol 5.5 Leaf temperature). In this approach, the time constant can be estimated by imposing periodic thermal forcing or a step change in temperature and fitting the resultant time series of leaf temperatures (Leigh et al., 2006; Vogel, 2009; Jones, 2014). Second, it can be calculated as a composite leaf trait comprising mass, specific heat capacity, total area, size, geometry, stomatal conductance, LMA, and LDMC (Michaletz et al., 2015, 2016):

where φ (dimensionless) is the ratio of projected to total leaf area, LMA is the leaf mass per area, LDMC is the leaf dry matter content, cp,d (J kg-1 K-1) is the specific heat capacity of dry leaf matter, and cp,w (J kg-1 K-1) is the specific heat capacity of water. A heat transfer coefficient h (W m-2 K-1) that considers convection, radiation, and transpiration can be calculated as:

![]() (simpler forms are given in the supplement of Michaletz et al. 2015).

(simpler forms are given in the supplement of Michaletz et al. 2015).

Here, ρa (kg m-3) is air density, cp,a (J kg-1 K-1) is the specific heat capacity of air at a constant pressure, and gh, gr, and gw are conductances to heat, radiation, and water vapour, respectively. These conductances vary with properties of the air (velocity, temperature, density) and leaf (type, size, stomatal conductance, emissivity) as described in (Michaletz et al., 2015). Finally, the psychrometric “constant” γ (Pa K-1) is given by γ = Pcp/0.622λ, where P (Pa) is the air pressure and λ (J kg-1) is the latent heat of vaporisation of water.

Measurement of leaf thermal traits is generally accomplished via manual measurement of in situ or destructively sampled leaves. This can occur at a fixed point in time (such as the peak of the growing season) or fixed intervals through time (e.g. to characterise temporal variation in thermal traits). For cases where the thermal time constant is estimated from temperature time series data, this may be accomplished via deployment of leaf thermocouples, infrared thermometers, or infrared cameras as described in protocol 5.5 Leaf temperature.

Where to start

Baraloto et al. (2010), Hulshof & Swenson (2010), Jones (2014), Pérez-Harguindeguy et al. (2013)

5.6.2 Special cases, emerging issues, and challenges

Efforts are underway to improve the land component of Earth system models (ESMs) by replacing plant functional types (which are conventionally prescribed to have fixed values of traits) with more realistic, continuous variation in functional traits (Kattge et al., 2011; Scheiter et al., 2013; Fyllas et al., 2014; van Bodegom et al., 2014; Wullschleger et al., 2014; Fisher et al., 2015; Sakschewski et al., 2015; Christoffersen et al., 2016). Temperature is a key driver of rates of plant metabolism, but ESMs may not accurately estimate the operating temperatures of plants because even though they include surface energy balance calculations, they generally do not accurately represent the spatial and temporal variation of leaf thermal traits (Dong et al., 2017). In offline dynamic global vegetation models (DGVMs) leaf temperature is normally assumed to equal ambient air temperature; but in reality leaf temperatures can differ from ambient air temperature (commonly by 3 to 6 ˚C and sometimes by up to 29 ˚C (Michaletz et al., 2016), suggesting that this approximation is unsatisfactory.

5.6.3 References

Theory, significance, and large datasets

BIEN: The Botanical Information and Ecology Network (http://bien.nceas.ucsb.edu/bien/); Jones (2014), Kattge et al. (2011), Michaletz et al. (2016)

More on methods and existing protocols

Campbell & Norman (1998), Ehleringer (1981), Gates (1980), Monteith & Unsworth (2013), Pérez-Harguindeguy et al. (2013)

All references

Ahn, H. K., Sauer, T. J., Richard, T. L., & Glanville, T. D. (2009). Determination of thermal properties of composting bulking materials. Bioresource Technology, 100(17), 3974-3981.

ASTM Standard E1269-11. (2011). Standard Test Method for Determining Specific Heat Capacity by Differential Scanning Calorimetry.

ASTM Standard E1933-14. (2014). Standard Practice for Measuring and Compensating for Emissivity Using Infrared Imaging Radiometers. ASTM International, West Conshohocken.

Baraloto, C., Paine, C. E. T., Patiño, S., Bonal, D., Hérault, B., & Chave, J. (2010). Functional trait variation and sampling strategies in species-rich plant communities. Functional Ecology, 24(1), 208-216.

Berry, J., & Bjorkman, O. (1980). Photosynthetic response and adaptation to temperature in higher plants. Annual Review of Plant Physiology, 31(1), 491-543.

Campbell, G. S., & Norman, J. M. (1998). An Introduction to Environmental Biophysics. New York: Springer Science+Business Media.

Christoffersen, B. O., Gloor, M., Fauset, S., Fyllas, N. M., Galbraith, D. R., Baker, T. R., … Meir, P. (2016). Linking hydraulic traits to tropical forest function in a size-structured and trait-driven model (TFS v.1-Hydro). Geoscientific Model Development, 9(11), 4227-4255.

Diemer, M., & Körner, C. (1996). Lifetime leaf carbon balances of herbaceous perennial plants from low and high altitudes in the Central Alps. Functional Ecology, 10(1), 33-43.

Dong, N., Prentice, I. C., Harrison, S. P., Song, Q. H., & Zhang, Y. P. (2017). Biophysical homoeostasis of leaf temperature: A neglected process for vegetation and land-surface modelling. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 26(9), 998-1007.

Dupont, C., Chiriac, R., Gauthier, G., & Toche, F. (2014). Heat capacity measurements of various biomass types and pyrolysis residues. Fuel, 115, 644-651.

Ehleringer, J. R. (1981). Leaf absorptances of Mohave and Sonoran desert plants. Oecologia, 49(3), 366-370.

Ehleringer, J. R. (1988). Changes in leaf characteristics of species along elevational gradients in the Wasatch Front, Utah. American Journal of Botany, 680-689.

Ehleringer, J. R. (2000). Temperature and energy budgets. In R. W. Pearcy, J. R. Ehleringer, H. A. Mooney, & P. W. Rundel (Eds.), Plant Physiological Ecology: Field methods and instrumentation (pp. 117-135). Dordrecht: Springer.

Enquist, B. J., Patrick Bentley, L., Shenkin, A., Maitner, B., Savage, V., Michaletz, S. T., … Malhi, Y. (2017). Assessing trait-based scaling theory in tropical forests spanning a broad temperature gradient. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 26, 1357-1373.

Fisher, R. A., Muszala, S., Verteinstein, M., Lawrence, P., Xu, C., McDowell, N. G., … Bonan, G. (2015). Taking off the training wheels: the properties of a dynamic vegetation model without climate envelopes. Geoscientific Model Development Discussions, 8(4), 3293-3357.

Fyllas, N. M., Gloor, E., Mercado, L. M., Sitch, S., Quesada, C. A., Domingues, T. F., … Lloyd, J. (2014). Analysing Amazonian forest productivity using a new individual and trait-based model (TFS v.1). Geoscientific Model Development, 7(4), 1251-1269.

Gates, D. M. (1980). Biophysical Ecology. New York: Springer-Verlag.

Hulshof, C. M., & Swenson, N. G. (2010). Variation in leaf functional trait values within and across individuals and species: an example from a Costa Rican dry forest. Functional Ecology, 24(1), 217-223.

Jones, H. G. (2014). Plants and Microclimate: A Quantitative Approach to Environmental Plant Physiology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kattge, J., Diaz, S., Lavorel, S., Prentice, I. C., Leadley, P., Bonisch, G., … Wirth, C. (2011). TRY – a global database of plant traits. Global Change Biology, 17(9), 2905-2935.

Keenan, T. F., & Niinemets, Ü. (2016). Global leaf trait estimates biased due to plasticity in the shade. Nature Plants, 3, 16201.

Knight, C. A., & Ackerly, D. D. (2003). Evolution and plasticity of photosynthetic thermal tolerance, specific leaf area and leaf size: congeneric species from desert and coastal environments. New Phytologist, 160(2), 337-347.

Körner, C., & Diemer, M. (1987). In situ photosynthetic responses to light, temperature and carbon dioxide in herbaceous plants from low and high altitude. Functional Ecology, 1(3), 179-194.

Leigh, A., Close, J. D., Ball, M. C., Siebke, K., & Nicotra, A. B. (2006). Leaf cooling curves: measuring leaf temperature in sunlight. Functional Plant Biology, 33(5), 515-519.

Malhi, Y., Girardin, C. A. J., Goldsmith, G. R., Doughty, C. E., Salinas, N., Metcalfe, D. B., … Silman, M. (2017). The variation of productivity and its allocation along a tropical elevation gradient: a whole carbon budget perspective. New Phytologist, 214(3), 1019-1032.

Michaletz, S. T. (2018). Evaluating the kinetic basis of plant growth from organs to ecosystems. New Phytologist, 219(1), 37-44.

Michaletz, S. T., Weiser, M. D., Zhou, J., Kaspari, M., Helliker, B. R., & Enquist, B. J. (2015). Plant thermoregulation: Energetics, trait-environment interactions, and carbon economics. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 30(12), 714-724.

Michaletz, S. T., Weiser, M. D., McDowell, N. G., Zhou, J., Kaspari, M., Helliker, B. R., & Enquist, B. J. (2016). The energetic and carbon economic origins of leaf thermoregulation. Nature Plants, 2, 16129.

Monteith, J. L., & Unsworth, M. (2013). Principles of Environmental Physics: Plants, Animals, and the Atmosphere. New York: Academic Press.

Pérez-Harguindeguy, N., Díaz, S., Garnier, E., Lavorel, S., Poorter, H., Jaureguiberry, P., … Cornelissen, J. H. C. (2013). New handbook for standardised measurement of plant functional traits worldwide. Australian Journal of Botany, 61(3), 167-234.

Sack, L., Melcher, P. J., Liu, W. H., Middleton, E., & Pardee, T. (2006). How strong is intracanopy leaf plasticity in temperate deciduous trees? American Journal of Botany, 93(6), 829-839.

Sakschewski, B., von Bloh, W., Boit, A., Rammig, A., Kattge, J., Poorter, L., … Thonicke, K. (2015). Leaf and stem economics spectra drive diversity of functional plant traits in a dynamic global vegetation model. Global Change Biology, 21(7), 2711-2725.

Scheiter, S., Langan, L., & Higgins, S. I. (2013). Next-generation dynamic global vegetation models: learning from community ecology. New Phytologist, 198(3), 957-969.

Shiklomanov, A. N., Dietze, M. C., Viskari, T., Townsend, P. A., & Serbin, S. P. (2016). Quantifying the influences of spectral resolution on uncertainty in leaf trait estimates through a Bayesian approach to RTM inversion. Remote Sensing of Environment, 183, 226-238.

van Bodegom, P. M., Douma, J. C., & Verheijen, L. M. (2014). A fully traits-based approach to modeling global vegetation distribution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 111(38), 13733-13738.

Vogel, S. (2009). Leaves in the lowest and highest winds: temperature, force and shape. New Phytologist, 183(1), 13-26.

Wang, H., Prentice, I. C., Davis, T. W., Keenan, T. F., Wright, I. J., & Peng, C. (2017). Photosynthetic responses to altitude: an explanation based on optimality principles. New Phytologist, 213(3), 976-982.

Wu, J., Albert, L. P., Lopes, A. P., Restrepo-Coupe, N., Hayek, M., Wiedemann, K. T., … Saleska, S. R. (2016). Leaf development and demography explain photosynthetic seasonality in Amazon evergreen forests. Science, 351(6276), 972-976.

Wu, J., Chavana-Bryant, C., Prohaska, N., Serbin, S. P., Guan, K., Albert, L. P., … Saleska, S. R. (2017). Convergence in relationships between leaf traits, spectra and age across diverse canopy environments and two contrasting tropical forests. New Phytologist, 214(3), 1033-1048.

Wu, J., Kobayashi, H., Stark, S. C., Meng, R., Guan, K., Tran, N. N., … Saleska, S. R. (2018). Biological processes dominate seasonality of remotely sensed canopy greenness in an Amazon evergreen forest. New Phytologist, 217(4), 1507-1520.

Wullschleger, S. D., Epstein, H. E., Box, E. O., Euskirchen, E. S., Goswami, S., Iversen, C. M., … Xu, X. (2014). Plant functional types in Earth system models: past experiences and future directions for application of dynamic vegetation models in high-latitude ecosystems. Annals of Botany, 114(1), 1-16.

Yamori, W., Hikosaka, K., & Way, D. A. (2014). Temperature response of photosynthesis in C3, C4, and CAM plants: temperature acclimation and temperature adaptation. Photosynthesis Research, 119(1), 101-117.

Zanoelo, E. F., Beninca, C., & Ribeiro, E. (2011). Thermophysical properties of Mate leaves: Experimental determination and theoretical effect of moisture content. Journal of Food Process Engineering, 34(6), 2124-2136.

Authors: Michaletz ST1,2,3, Blonder B4,5

Reviewer: Prentice IC6

Affiliations

1 Earth and Environmental Sciences Division, Los Alamos National Laboratory, Los Alamos, USA

2 Biosphere 2 and Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, University of Arizona, Tucson, USA

3 Department of Botany and Biodiversity Research Centre, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada

4 Environmental Change Institute, School of Geography and the Environment, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK

5 School of Life Sciences, Arizona State University, Tempe, USA

6 AXA Chair Programme in Biosphere and Climate Impacts, Department of Life Sciences, Imperial College London, Ascot, UK