Authors: Lembrechts JJ1, Zinnert JC², Mänd P³, De Boeck HJ1

Reviewer: Porcar Castell A4

Measurement unit: Fv/Fm or related variables; Measurement scale: leaf part; Equipment cost: €€–€€€; Running costs: €; Installation effort: low; Maintenance effort: medium (frequent recording); Knowledge need: medium to high (for interpretation); Measurement mode: manual

Chlorophyll fluorescence can be used as an indirect non-invasive measurement of photosystem II (PSII) efficiency. The principle underlying it is relatively simple. The fate of light energy absorbed by chlorophyll molecules in a leaf is one of the following: (i) it can be used to drive photosynthesis, (ii) excess energy can be dissipated as heat, or (iii) the energy can be re‐emitted as light with a longer wavelength (Maxwell & Johnson, 2000), a process called chlorophyll fluorescence. These three processes occur in competition, as they rely on the same energy source – the absorbed photons. Hence, measuring the yield of chlorophyll fluorescence can provide information on changes in both the efficiency of photochemistry and heat dissipation (Kautsky & Hirsch, 1931; Maxwell & Johnson, 2000).

The proven effects of both abiotic and biotic stressors on this energy partitioning in PSII (and the subsequent fluorescence yield), combined with the ease of the measurements, have made chlorophyll fluorescence a widely applied technique as an indicator of stress in leaves, in climate-change studies, and beyond (Lichtenthaler, 1988; Lichtenthaler & Miehé, 1997; Ogaya & Peñuelas, 2003; Souza et al., 2004; Takahashi & Murata, 2008). Applications include its role as an indicator of crop performance and tree vitality (Lichtenthaler et al., 1986; Baker & Rosenqvist, 2004), as well as of abiotic (e.g. drought or heat stress; Havaux, 1992; Ogaya & Peñuelas, 2003) and biotic (e.g. plant-pathogen interactions; Lang, 1995; Chaerle et al., 2004) stressors, showing its versatility as a tool to study plant responses to environmental factors in a wide range of observational and experimental studies.

5.1.1 What and how to measure?

Phenomenology

When a leaf is transferred from darkness to light, excitation energy captured by chlorophyll molecules in the antenna is rapidly transferred to open/oxidised reaction centres of photosystem II (PSII), progressively reducing them (Maxwell & Johnson, 2000). During the first seconds of illumination, this gives rise to an increase in the yield of chlorophyll fluorescence (the Kautsky effect, Kautsky & Hirsch, 1931). When the light input is sustained, however, the fluorescence level typically starts to fall again, over a timescale of seconds to minutes. This so-called fluorescence quenching results from the two above-mentioned processes competitively using the same incoming energy: “photochemical quenching”, the use of excitation energy in photosynthesis, and “non-photochemical quenching”, the use of excitation energy in heat dissipation. Over time, various measurement techniques have been developed to measure fluorescence yield and disentangle these different quenching components, ranging from traditional measurements on single, dark-adapted leaves, over pulse amplitude modulated (PAM) measurements to large-scale remote sensing assessments of whole canopies using passive fluorescence methods.

Where to start

Krause & Weis (1991), Lazár (2015), Lichtenthaler (1988), Maxwell & Johnson (2000), Murchie & Lawson (2013), Souza et al. (2004)

Main instrumentation

- a) Dark-adapted measurements

Dark-adapted fluorescence measurements are used to mimic night conditions by avoiding the variation in fluorescence and quenching caused by instantaneous illumination (Porcar‐Castell, 2011). The purpose of this dark acclimation is to re-oxidise the electron acceptors in PSII (which takes only a few seconds) and to relax all the reversible non-photochemical quenching, which may take a few minutes or hours, depending on plant species, temperature, stress levels, and prior light conditions (Demmig‐Adams & Adams, 2006; Porcar-Castell et al., 2014).

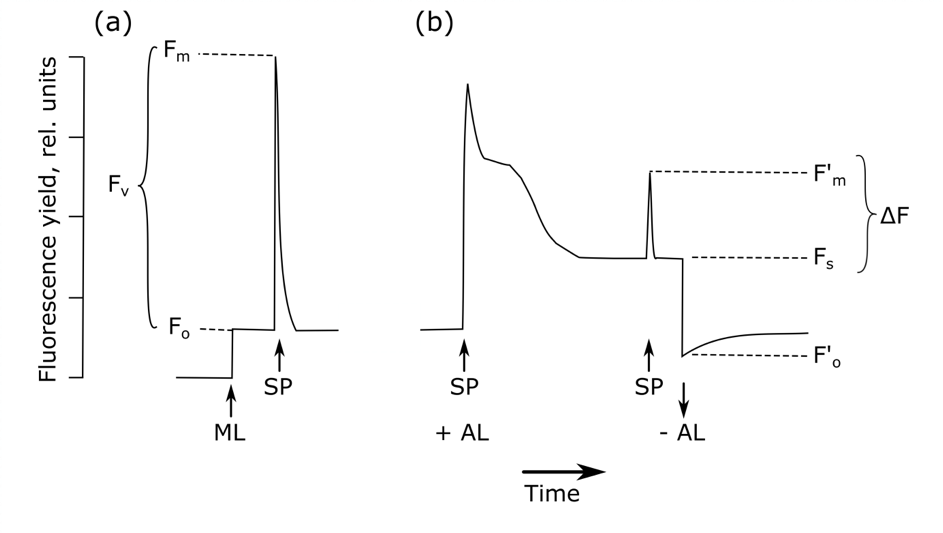

After dark-adaptation, background fluorescence (Fo) is measured with a measuring light too weak to start photochemical reactions (Figure 5.1.1, Bolhàr-Nordenkampf & Öquist, 1993). Subsequent application of a high intensity, short duration flash of light to this dark-adapted leaf closes all reaction centres (Maxwell & Johnson, 2000). The fluorescence yield reaches a value equivalent to that which would be attained in the absence of any photochemical quenching, the maximum fluorescence, Fm. The difference between Fo and Fm is the variable fluorescence, Fv. It has been shown theoretically and empirically that Fv / Fm (i.e. (Fm – Fo) / Fm) is a robust indicator of the maximum quantum yield of PSII chemistry (Butler, 1978). For unstressed leaves, the value of Fv / Fm is fairly consistent, with observed values of 0.832 ± 0.004, correlating with the maximum quantum yield of photosynthesis (Björkman & Demmig, 1987), while a stressor would reduce this value. Dark-adapted or pre-dawn Fv / Fm thus provides a useful relative indication of substantial photoinhibition or down-regulation of PSII in relation to non-specific stressors (Murchie & Lawson, 2013), although it is worth noting that it cannot be used as an accurate quantitative value of the quantum yield, among others due to the significant variation in this value depending on leaf morphology, species, and fluorometer (Baker, 2008). More detailed measurements of the rise from Fo to Fm at a resolution of μs and the specific pattern – called O-J-I-P – this transition follows, can provide additional insights in the photochemical efficiency of PSII (Strasser & Govindjee, 1992).

The timing of dark-adaptation is thus crucial to acquire accurate measurements of Fv / Fm. Often, a period of 15 to 20 minutes is recommended. It has, however, been shown that low levels of quenching can still be observed after a whole night or even 24 hours of dark-adaption (Baker, 2008). There are indeed different types of non-photochemical quenching with different temporal components, being either rapidly or slowly reversible non-photochemical quenching (Porcar‐Castell, 2011; Lazár, 2015). As one can never be sure that all samples have been dark-adapted for the same time, pre-dawn conditions are often preferred in the field for stress assessments (Maxwell & Johnson, 2000; Murchie & Lawson, 2013). If this cannot be achieved, leaf clips – usually provided with the fluorometer – can be used to dark-adapt a leaf (or leaf part) for a fixed period of time at any time of the day (Figure 5.1.2).

Modern handheld fluorometers (both plant efficiency analysers (PEA) and pulse amplitude modulated (PAM) fluorometers) automatically provide all the mentioned F-values after initiating the necessary measurement light and saturating light pulse, making the actual measurements easy, fast, and practical to perform in-situ without harvesting the leaves. For a good overview of the many possible pitfalls in the interpretation of these measurements, see Murchie & Lawson (2013).

- b) Light-adapted measurements

Measurement of chlorophyll fluorescence has become even more versatile with “modulated” fluorometers, which rely on the selective monitoring of the fluorescence yield from rapid repetitive high-frequency light pulses with a measuring beam, while the detector is tuned to detect only fluorescence excited by the measuring light (Quick & Horton, 1984; Schreiber et al., 1986; Maxwell & Johnson, 2000; Souza et al., 2004). This approach allows the measurement of fluorescence dynamics under illumination, as the recorded fluorescence is coming from a modulated light source of constant intensity instead of from ambient light. So, while ambient fluorescence is controlled by both incoming light and current PSII energy partitioning status, PAM fluorescence is only controlled by the current PSII energy partitioning status, allowing one to probe PSII much more easily.

The light-adapted measurement can be used to estimate changes in the quantum yield of PSII (i.e. the proportion of light absorbed by chlorophyll in PSII that is used in photochemistry; Genty et al., 1989; Maxwell & Johnson, 2000). ΔF / F′m is calculated as the relationship between maximal fluorescence in a light-adapted leaf after a saturating pulse of light (F’m) and steady-state fluorescence prior to any saturating pulse (Fs or Ft, depending on the source): (F’m – Fs) / F’m (Figure 5.1.1). Since ΔF / F′m changes with light intensity, it is important to compare samples at similar levels of photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) (Murchie & Lawson, 2013). Other approaches have restricted measurements to conditions of saturating PAR for photosynthesis (Murchie & Lawson, 2013).

For a description of additional parameters provided by the PAM methodology, see section 5.1.2 Special cases, emerging issues, and challenges. Modern PAM-fluorometers are easy to use, and only require the attachment of a leaf clip to the leaf and one click of a button to initiate the necessary measurement pulses (Figure 5.1.3). In contrast to dark-adapted measurements, the timing of measurements is less critical, yet one might want to make sure comparable conditions are used for each measurement. Again, interpretation of the results can encounter several pitfalls; for a good overview see Murchie & Lawson (2013).

- c) New fluorescence methods: solar-induced fluorescence

More recent developments in the field now allow remote measurements of solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence (SIF), providing new ways to track photosynthesis and gross primary productivity of terrestrial ecosystems (Meroni et al., 2009; Frankenberg et al., 2011; Guanter et al., 2014). Importantly, the spatiotemporal and methodological context of these new applications is very different from the traditional methods described above, both in terms of phenomenology as well as in terms of instrumentation (Porcar-Castell et al., 2014). For example, unlike PAM, SIF can only be estimated within very narrow spectral bands where the radiation reaching the Earth’s surface has been greatly attenuated due to gas absorption, either in the solar photosphere (Fraunhofer lines) or Earth’s atmosphere (e.g. oxygen bands). Because SIF is not based on PAM measurements, nor can it be measured under saturating pulses, its interpretation is much more complex than that of PAM fluorescence. This is a rapidly expanding field however, in which ground instrumentation is being developed (e.g. Porcar-Castell et al., 2014) and in which new space missions are providing increasing amounts of data. Overall, connecting active PAM and passive SIF measurements may provide new opportunities for upscaling ecological hypotheses from the leaf to the canopy and landscape levels.

Where to start

Baker (2008), Björkman & Demmig (1987), Bolhàr-Nordenkampf & Öquist (1993), Butler (1978), Genty et al. (1989), Porcar-Castell et al. (2014), Quick & Horton (1984)

5.1.2 Special cases, emerging issues, and challenges

Special cases

PAM fluorescence measurement devices have been adapted recently for continuous field monitoring (MONI-PAM; Porcar-Castell et al., 2008). Such instruments measure chlorophyll fluorescence, PAR, and temperature in the field over a certain period, on exactly the same leaf area and thus facilitate the estimation of both rapidly reversible and sustained non photochemical quenching.

In vivo fluorescence measurement techniques, as described here, have also been adapted for use in aquatic environments on lower photosynthetic organisms such as algae. The assessment of largely identical fluorescence parameters is possible (Campbell et al., 1998; Kromkamp & Forster, 2003), although alternative fluorometers and some modifications of the above-mentioned parameters might be needed (Campbell et al., 1998).

Chlorophyll fluorescence measurements are often combined with other techniques and instrumentation and help provide a unique research tool to answer a myriad of other questions. For example, combining chlorophyll fluorescence with infra-red gas exchange (IRGA; also see protocols 5.7 Stomatal conductance and 5.15 Water-use efficiency) techniques provides information on the correlation between PSII photosynthetic efficiency and the CO2 assimilation rate by eliminating photorespiration (Murchie & Lawson, 2013). Such exercises, however, require good insights into the processes at hand to avoid misinterpretation. For example, the abovementioned technique often relies on absolute estimates of the electron transport rate (ETR) through fluorescence, yet the latter is based on several assumptions (see below Challenges b) Light-adapted measurements; e.g. Yin et al., 2009).

Challenges

- a) Dark-adapted measurements

With Fv / Fm being so easy to measure in dark-adapted leaves, it has proven an invaluable measure of plant stress. Its interpretation, however, is not always straightforward (Murchie & Lawson, 2013). First, it is not easy to assess the underlying cause of the decline in the performance of PSII as assessed through Fv / Fm. Certain stress conditions such as drought might not only inactivate PSII reaction centres and reduce Fv / Fm through a rise in Fo, but they might also change the optical properties of the leaf, in which case the individual observed values of Fm and Fo may be a result of changes in leaf absorptance (Murchie & Lawson, 2013). This will affect the estimation of NPQ but has, a priori, no effect on Fv / Fm since the reduction in F due to absorption cancels out in the ratio. Additionally, a decline in Fv / Fm does not necessarily imply that the photosynthetic performance of the plant is compromised (Demmig‐Adams & Adams, 2006; Murchie & Niyogi, 2011; Murchie & Lawson, 2013). It is worth mentioning that a sufficiently high light intensity is necessary to induce closure of PSII (Takahashi & Murata, 2008) before a difference in Fv / Fm is observed between treatments. Fv / Fm measurements as an indicator of stress are also limited to leaves: stress in other plant parts might not be reflected by a reduction in fluorescence yield (Murchie & Lawson, 2013). In that regard, leaf selection itself is also important. One should note that fluorescence measurements are highly heterogeneous at the within-plant level, especially under stress conditions. Comparing leaves in similar conditions, for example consistently working with the youngest fully expanded leaf or with leaves growing under similar light regimes, can help to reduce such measurement noise.

- b) Light-adapted measurements

The electron transport rate (ETR, μmol photon m-2 s-1) can be derived from the quantum yield as measured by the PAM, by multiplying ΔF / F′m with the light intensity (PAR), fractional absorptance of light by the leaf (measured using an integrating sphere), and the partitioning of energy between PSII and PSI (0.5, yet dependent on wavelength of the light, time, and species; Maxwell & Johnson, 2000). This requires an accurate determination of the incident PAR on the leaf, the proportion of incident PAR that is absorbed by the leaf, and the fraction of absorbed PAR that is received by PSII. As it is not generally practical to measure the fractional absorptance of light (but see Olascoaga et al., 2016), it is often estimated as 0.84 for C3 plants (Björkman & Demmig, 1987). The need for such general assumptions suggests it is best to avoid using ETR to draw conclusions between samples. Alternatively, ETR can be expressed in relative changes among samples by multiplying ΔF / F′m by PAR (Maxwell & Johnson, 2000).

The PAM measuring systems can be used to disentangle the various sources of fluorescence quenching as either photochemical or non-photochemical quenching (Roháček & Barták, 1999), allowing a more detailed assessment of the processes driving photosynthesis and energy dissipation. The first saturating light pulse on a dark-adapted leaf closes all reaction centres (qP = 0) and causes fluorescence to rise to the peak value Fm. Next, a continuous actinic light source induces both photochemical and non-photochemical quenching, together dictating the level of fluorescence. Once both types of quenching reach a steady state, fluorescence will be constant (steady-state fluorescence, Fs). Subsequent saturating light pulses will now result in peaks with the maximal fluorescence level F’m, lower than the initial FM due to the initiation of non-photochemical quenching. The photochemical quenching (qP) can then be calculated as (F’m – Fs) / (F’m – F’o), with F’o the new level of background fluorescence when actinic light is switched off again (van Kooten & Snel, 1990). While this parameter appears very similar to ΔF / F′m described in 1.2b, qP gives an indication of the proportion of PSII reaction centres that are open, in contrast to the proportion of absorbed energy being used in photochemistry described by ΔF / F′m.

At the time of the short saturating light pulses, all PSII acceptors will be reduced, again inhibiting all photochemical quenching. All remaining quenching compared to the dark-adapted control (Fm) thus has to be non-photochemical (Schreiber et al., 1986), allowing the calculation of qN as (Fm – F’m) / (Fm – F’o). Throughout the years, many alternative quenching parameters have been proposed, tackling several issues with the two listed. For more details see Roháček (2002) and Lazár (2015).

Selection of leaves

Care must be taken when making comparisons with light-adapted measurements as ΔF / F′m can vary based on light levels and the light saturation behaviour of plants growing under different field conditions (Maxwell & Johnson, 2000). Comparative measurements can be obtained by standardising light levels among plants or capturing a range of light conditions on one plant. Commonly, light-saturated, fully expanded leaves are selected when taking measurements in open environments. In shaded environments, light-adapted parameters will quickly change based on sunflecks (Adams et al., 1999; Maxwell & Johnson, 2000).

5.1.3 References

Theory, significance, and large datasets

Baker (2008), Kautsky & Hirsch (1931), Krause and Weis (1991), Maxwell & Johnson (2000), Schreiber et al. (1995)

More on methods and existing protocols

Campbell et al. (1998), Kolber et al. (2005), Lazár (2015), Maxwell & Johnson (2000), Murchie & Lawson (2013)

All references

Adams, W., Demmig‐Adams, B., Logan, B., Barker, D., & Osmond, C. B. (1999). Rapid changes in xanthophyll cycle‐dependent energy dissipation and photosystem II efficiency in two vines, Stephania japonica and Smilax australis, growing in the understory of an open Eucalyptus forest. Plant, Cell & Environment, 22(2), 125-136.

Baker, N. R. (2008). Chlorophyll fluorescence: a probe of photosynthesis in vivo. Annual Review of Plant Biology, 59, 89-113.

Baker, N. R., & Rosenqvist, E. (2004). Applications of chlorophyll fluorescence can improve crop production strategies: an examination of future possibilities. Journal of Experimental Botany, 55(403), 1607-1621.

Björkman, O., & Demmig, B. (1987). Photon yield of O2 evolution and chlorophyll fluorescence characteristics at 77K among vascular plants of diverse origins. Planta, 170(4), 489-504.

Bolhàr-Nordenkampf, H., & Öquist, G. (1993). Chlorophyll fluorescence as a tool in photosynthesis research. In D. O. Hall, J. M. O. Scurlock, H. R. Bolhàr-Nordenkampf, R. C. Leegood, & S. P. Long (Eds.), Photosynthesis and Production in a Changing Environment (pp. 193-206). Netherlands: Springer.

Butler, W. L. (1978). Energy distribution in the photochemical apparatus of photosynthesis. Annual Review of Plant Physiology, 29(1), 345-378.

Campbell, D., Hurry, V., Clarke, A. K., Gustafsson, P., & Öquist, G. (1998). Chlorophyll fluorescence analysis of cyanobacterial photosynthesis and acclimation. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews, 62(3), 667-683.

Chaerle, L., Hagenbeek, D., de Bruyne, E., Valcke, R., & van der Straeten, D. (2004). Thermal and chlorophyll-fluorescence imaging distinguish plant-pathogen interactions at an early stage. Plant and Cell Physiology, 45(7), 887-896.

Demmig‐Adams, B., & Adams, W. W. (2006). Photoprotection in an ecological context: the remarkable complexity of thermal energy dissipation. New Phytologist, 172(1), 11-21.

Frankenberg, C., Fisher, J. B., Worden, J., Badgley, G., Saatchi, S. S., Lee, J. E., … Kuze, A. (2011). New global observations of the terrestrial carbon cycle from GOSAT: Patterns of plant fluorescence with gross primary productivity. Geophysical Research Letters, 38(17) GL048738.

Genty, B., Briantais, J.-M., & Baker, N. R. (1989). The relationship between the quantum yield of photosynthetic electron transport and quenching of chlorophyll fluorescence. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta – General Subjects, 990(1), 87-92.

Guanter, L., Zhang, Y., Jung, M., Joiner, J., Voigt, M., Berry, J. A., … Lee, J.-E. (2014). Global and time-resolved monitoring of crop photosynthesis with chlorophyll fluorescence. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 111(14), E1327-E1333.

Havaux, M. (1992). Stress tolerance of photosystem II in vivo: antagonistic effects of water, heat, and photoinhibition stresses. Plant Physiology, 100(1), 424-432.

Kautsky, H., & Hirsch, A. (1931). Neue versuche zur kohlensäureassimilation. Naturwissenschaften, 19(48), 964-964.

Kolber, Z., Klimov, D., Ananyev, G., Rascher, U., Berry, J., & Osmond, B. (2005). Measuring photosynthetic parameters at a distance: laser induced fluorescence transient (LIFT) method for remote measurements of photosynthesis in terrestrial vegetation. Photosynthesis Research, 84(1-3), 121-129.

Krause, G., & Weis, E. (1991). Chlorophyll fluorescence and photosynthesis: the basics. Annual Review of Plant Biology, 42(1), 313-349.

Kromkamp, J. C., & Forster, R. M. (2003). The use of variable fluorescence measurements in aquatic ecosystems: differences between multiple and single turnover measuring protocols and suggested terminology. European Journal of Phycology, 38(2), 103-112.

Lang, M. (1995). Studies on the blue-green and chlorophyll fluorescences of plants and their application for fluorescence imaging of leaves. Karlsruhe Contribution to Plant Physiology, 29, 1-110.

Lazár, D. (2015). Parameters of photosynthetic energy partitioning. Journal of Plant Physiology, 175, 131-147.

Lichtenthaler, H. K. (1988). In vivo chlorophyll fluorescence as a tool for stress detection in plants. In H. K. Lichtenthaler (Ed.), Applications of Chlorophyll Fluorescence in Photosynthesis Research, Stress Physiology, Hydrobiology and Remote Sensing (pp. 129-142). Netherlands: Springer.

Lichtenthaler, H. K., & Miehé, J. A. (1997). Fluorescence imaging as a diagnostic tool for plant stress. Trends in Plant Science, 2(8), 316-320.

Lichtenthaler, H., Buschmann, C., Rinderle, U., & Schmuck, G. (1986). Application of chlorophyll fluorescence in ecophysiology. Radiation and Environmental Biophysics, 25(4), 297-308.

Maxwell, K., & Johnson, G. N. (2000). Chlorophyll fluorescence—a practical guide. Journal of Experimental Botany, 51(345), 659-668.

Meroni, M., Rossini, M., Guanter, L., Alonso, L., Rascher, U., Colombo, R., & Moreno, J. (2009). Remote sensing of solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence: Review of methods and applications. Remote Sensing of Environment, 113(10), 2037-2051.

Murchie, E. H., & Lawson, T. (2013). Chlorophyll fluorescence analysis: a guide to good practice and understanding some new applications. Journal of Experimental Botany, 64(13), 3983-3998.

Murchie, E. H., & Niyogi, K. K. (2011). Manipulation of photoprotection to improve plant photosynthesis. Plant Physiology, 155(1), 86-92.

Ogaya, R., & Peñuelas, J. (2003). Comparative field study of Quercus ilex and Phillyrea latifolia: photosynthetic response to experimental drought conditions. Environmental and Experimental Botany, 50(2), 137-148.

Olascoaga, B., Mac Arthur, A., Atherton, J., & Porcar-Castell, A. (2016). A comparison of methods to estimate photosynthetic light absorption in leaves with contrasting morphology. Tree Physiology, 36(3), 368-379.

Porcar‐Castell, A. (2011). A high‐resolution portrait of the annual dynamics of photochemical and non‐photochemical quenching in needles of Pinus sylvestris. Physiologia Plantarum, 143(2), 139-153.

Porcar-Castell, A., Pfündel, E., Korhonen, J. F., & Juurola, E. (2008). A new monitoring PAM fluorometer (MONI-PAM) to study the short-and long-term acclimation of photosystem II in field conditions. Photosynthesis Research, 96(2), 173-179.

Porcar-Castell, A., Tyystjärvi, E., Atherton, J., van der Tol, C., Flexas, J., Pfündel, E. E., … Berry, J. A. (2014). Linking chlorophyll a fluorescence to photosynthesis for remote sensing applications: mechanisms and challenges. Journal of Experimental Botany, 65(15), 4065-4095.

Quick, W., & Horton, P. (1984). Studies on the induction of chlorophyll fluorescence in barley protoplasts. II. Resolution of fluorescence quenching by redox state and the transthylakoid pH gradient. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences, 220(1220), 361-370.

Roháček, K. (2002). Chlorophyll fluorescence parameters: the definitions, photosynthetic meaning, and mutual relationships. Photosynthetica, 40(1), 13-29.

Roháček, K., & Barták, M. (1999). Technique of the modulated chlorophyll fluorescence: basic concepts, useful parameters, and some applications. Photosynthetica, 37(3), 339.

Schreiber, U., Schliwa, U., & Bilger, W. (1986). Continuous recording of photochemical and non-photochemical chlorophyll fluorescence quenching with a new type of modulation fluorometer. Photosynthesis Research, 10(1-2), 51-62.

Schreiber, U., Bilger, W., & Neubauer, C. (1995). Chlorophyll fluorescence as a nonintrusive indicator for rapid assessment of in vivo photosynthesis. In E.-D. Schultze, & M. M. Caldwell (Eds.), Ecophysiology of Photosynthesis (pp. 49-70). Berlin: Springer.

Souza, R., Machado, E., Silva, J., Lagôa, A., & Silveira, J. (2004). Photosynthetic gas exchange, chlorophyll fluorescence and some associated metabolic changes in cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) during water stress and recovery. Environmental and Experimental Botany, 51(1), 45-56.

Strasser, R. J., & Govindjee (1992). The Fo and the O-J-I-P fluorescence rise in higher plants and algae. In J. H. Argyroudi-Akoyunoglou (Ed.), Regulation of Chloroplast Biogenesis (pp. 423-426). Botston: Springer.

Takahashi, S., & Murata, N. (2008). How do environmental stresses accelerate photoinhibition? Trends in Plant Science, 13(4), 178-182.

van Kooten, O., & Snel, J. F. (1990). The use of chlorophyll fluorescence nomenclature in plant stress physiology. Photosynthesis Research, 25(3), 147-150.

Yin, X., Struik, P. C., Romero, P., Harbinson, J., Evers, J. B., van der Putten, P. E. L., & Vos, J. A. N. (2009). Using combined measurements of gas exchange and chlorophyll fluorescence to estimate parameters of a biochemical C3 photosynthesis model: a critical appraisal and a new integrated approach applied to leaves in a wheat (Triticum aestivum) canopy. Plant, Cell & Environment, 32(5), 448-464.

Authors: Lembrechts JJ1 Zinnert JC², Mänd P³, De Boeck HJ1

Reviewer: Porcar Castell A4

Affiliations

1 Centre of Excellence PLECO (Plants and Ecosystems), Biology Department, University of Antwerp, Wilrijk, Belgium

2 Department of Biology, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, USA

3 Institute of Ecology and Earth Sciences, Tartu University, Tartu, Estonia

4 Optics of Photosynthesis Laboratory, Institute for Atmospheric and Earth System Research/Forest Sciences, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland