Author: Fuchslueger L1

Reviewer: Hansen K2,3, Lee H4, Schmidt IK5

Measurement unit: carbon ha-1 yr-1; Measurement scale: plot, site; Equipment costs: €€; Running costs: €€–€€€; Installation effort: medium; Maintenance effort: medium; Knowledge need: medium to high; Measurement mode: manual

Soil organic matter (SOM) is one of the largest terrestrial carbon pools (Schlesinger & Bernhardt, 2013) storing more than twice as much C (carbon; in the form of soil organic C: SOC) as the atmosphere (Schmidt et al., 2011). Changes in this immense stock induced by global climate change can have far-reaching effects and negative feedbacks on Earth’s climate. The SOM and SOC pool size is balanced by the rate of SOM formation and by its mineralisation to inorganic carbon (CO2), but also by losses through erosion (see protocol 2.2.10 Soil water erosion) or leaching (see protocol 2.2.9 Soil leaching) of dissolved organic carbon (DOC) (Schmidt et al., 2011; Harden et al., 2018). The World Inventory of Soil property Estimates (WISE) project WISE30s is constantly being updated and aims to calculate global soil organic stocks to a depth of 2 m, with defined uncertainty estimates (Batjes, 2016).

Climatic factors have been regarded as primary controls on SOM stabilisation and decomposition and over the resulting SOC pool in empirical and modelling approaches (Davidson & Janssens, 2006; Carvalhais et al., 2014; Luo et al., 2016). Moreover, SOM composition, its spatial or temporal accessibility for decomposer organisms (e.g. protected by occlusion, hydrophobicity, encapsulation), or its interaction with mineral surfaces can influence SOM decomposition and stabilisation (Trumbore & Zheng, 1996; Kögel-Knabner, 2002; Six et al., 2002; von Lützow et al., 2007). Importantly, SOM stabilisation and decompostion can respond differently to land management, changes in nutrient availability through fertilisation or nutrient deposition, and changing environmental conditions. It is important to increase our understanding of SOM decomposition to better project effects under future climate- and global-change scenarios (Cotrufo et al., 2015; Harden et al., 2018).

2.2.8.1 What and how to measure?

There has been a rapid development of techniques to study the soil carbon cycle. One important indicator of SOM decomposition is to determine the soil CO2 release or soil respiration by heterotrophic organisms. For more details on soil CO2 flux measurements see protocol 2.2.3 Soil CO2 (and other trace gas) fluxes. Despite measuring CO2 fluxes in the field, SOM decomposition can be estimated from short-term lab incubation by measuring CO2 and microbial biomass and activity. Other common ways to estimate SOM decomposition is to determine SOM stocks in bulk soils (see protocol 1.4.2 Soil nutrients) or in different SOM fractions and monitor potential changes over time, and additionally to determine chemical SOM composition (such as C:N, lignin:N ratios). Stable C isotopes (12C, 13C) are commonly used to determine decomposition rates and turnover, and radiocarbon (14C) or “bomb-carbon” dating for determining SOM-age.

Measuring CO2 efflux of soils in lab incubations is a relatively low-cost method that can give a fast and rough overview of the microbial activity and microbe-mediated SOM decomposition. Bulk soil SOC and 13C determination by elemental analysis isotope ratio mass spectroscopy (EA-IRMS) is one of the most common and affordable methods to get a quick overview of the C stocks in the soil and requires only a small number of soil aliquots. SOM fractionation gives a very detailed overview, but is more time-consuming and needs expensive chemicals (sodium-polytungstate). Using crop cover changes to trace 13C shifts in the natural abundance of C3 and C4 plant isotope signals over time is cheaper but requires detailed documentation of land-use changes. In contrast, using standardised 13C labelled plant material as part of the SOM is more expensive, but it is better able to trace changes at finer scales. Radiocarbon dating is also a rather costly method.

Short-term lab incubations

Use compound samples of fresh soils (depending on the research question) and keep moisture content and temperature constant (depending on soil and ecosystem). Soils are incubated and CO2 should be measured at regular intervals (e.g. weekly) and microbial biomass (see protocol 2.2.1 Soil microbial biomass – C, N and P) determined. Respiration rates can be calculated on a soil mass basis (dry soil), or per C content, or microbial C content.

C stocks, SOM fractions, and chemical composition

Bulk soil and functional SOM fractions can be analysed for C content, isotopic signature, or C age (see below). In non-calcareous soils, bulk soil C can be considered as total SOM C. In calcareous soils, samples should first be treated with 10% HCl to remove carbonates and subsequently oven dried at 60 °C for 48 h. Soil C and N content can be measured from dried and finely ground soil samples by an Elemental Analyser. SOM decomposition can be determined indirectly by monitoring net changes in C stocks in bulk soil or in different SOM fractions over time. Soil sample collection in the field and preparation are described below (see Installation, field operation, maintenance, interpretation).

SOM fractions can be classified to functional pools following a three-step fraction scheme to isolate their C pools based on physical, chemical, and biochemical protection mechanisms: a full description and comparison of different methods can be found in von Lützow et al. (2007). Here, we report on the methodology described by Stewart et al. (2008). This fractionation scheme is based on the assumed link between different fractions and different protection mechanisms involved in the stabilisation of organic C within the respective pools as described by Six et al. (2002). The physical fractionation of air-dried soil is conducted to obtain three size fractions: > 250 μm (coarse unprotected particulate organic matter, cPOM), 53–250 μm (microaggregate fraction: μagg), and < 53 μm (easily dispersed silt and clay: dSilt and dClay). To obtain these fractions, air-dried soil is sequentially wet-sieved through a 2 mm and 250 μm sieve to flush μagg and finer particles through the 250 μm mesh. Material that is larger than 250 μm (cPOM and sand) remains in the sieve. Microaggreagates are collected in a 53 μm sieve that is subsequently wet-sieved to separate the easily dispersed silt- and clay-sized fractions from water-stable μagg. The resulting suspension is centrifuged to separate the dSilt and dClay fractions. All collected fractions are oven dried (at 60 °C for 48 h) and weighed. The second step is the isolation of μagg. A solution of 1.85 g cm-3 sodium-polytungstate (SPT) is used to collect the floating fine unprotected POM (or light fraction: LF). The remaining heavy fraction is dispersed, by shaking with glass beads, and passed through a 53 μm sieve. This separates the microaggregate protected POM (> 53 μm, iPOM) and the microaggregate derived silt and clay sized fractions (μSilt and μClay). In a further step, the isolated silt and clay sized fractions can be hydrolysed if necessary (see further description in Stewart et al., 2008). All individual fractions can be dried and used to determine C content, and for stable isotope and radiocarbon analysis (see below in section SOM age using 14C (radiocarbon) dating (long-term approach).

Depending on the research question, not only SOM quantity, but also SOM quality, i.e. the chemical composition of SOM can be determined (Kögel-Knabner, 2002; von Lützow et al., 2006; Schmidt et al., 2011; Poeplau et al., 2016). Total C and total N can be measured in dried and ground soils as described above in section C stocks, SOM fractions, and chemical composition. The chemical composition of SOM can give information on the degree of plant v. secondary resources derived by decomposers and can be determined by chemolytic techniques or analytical pyrolysis in combination with solid-state 13C-NMR spectroscopy or mass spectrometry on dried and ground soils (Golchin et al., 1994; Kögel-Knabner, 2002; Schmidt et al., 2011).

SOM turnover dynamics using 13C isotopes (short-term approaches)

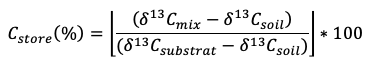

Stable isotopes, particularly the stable isotope of C (13C), are a powerful means of investigating SOM decomposition. Applications range from taking advantage of changes in crop cover using natural abundance of 13C, to 13C labelling studies that trace 13C from marked organic material into SOM and CO2. Crop changes from C3 plants (average δ13C value of -27 ‰) to C4 plants (e.g. maize; average δ13C values of -13 ‰) or vice versa, will lead to a continuous modification of the 13C signal of the SOM (Balesdent & Mariotti, 1996). Over time, SOM will steadily change towards the new crop 13C, which allows the study of C turnover in SOM. Similarly, isotopically different litter (Djukic et al., 2013) or 13C labelled plant material (leaf and/or roots) can be used to trace C sequestration into total SOM or different SOM fractions (Soong & Cotrufo, 2015). The proportion of new C incorporated into SOM (Cstore) can be calculated as follows:

where δ13Cmix is the δ13C value of the SOM and labelled litter mix after incubation, δ13Csoil is the initial δ13C value of the soil before incubation, and δ13Csubstrate is the δ13C value of the (labelled) litter used for the decomposition experiment (Djukic et al., 2013). Sample collection in natural abundance studies and installation effort of isotopically different or labelled organic matter is described below (see Installation, field operation, maintenance, interpretation).

SOM age using 14C (radiocarbon) dating (long-term approach)

Atmospheric CO2 contains trace amounts of the radioactive isotope 14C (radiocarbon), which is produced naturally in the lower stratosphere and occurs at a relatively constant concentration in the atmosphere. Since all plants take up 14C through photosynthesis they reflect the 14C concentration of the atmosphere. Upon plant death the radiocarbon concentration begins to decrease through radioactive decay with a half-life of 5730 years; hence, the 14C content of organic matter can serve as a measure of C age and can be translated into C residence time in a soil. Furthermore, advantage can be taken of the so called 14C “bomb-carbon” peak that was caused by anthropogenic nuclear tests in the early 1960s that increased the proportion of 14C in the atmosphere (Trumbore, 2009). For both approaches, both archived and recent samples are required for 12C and 14C analyses. Usually, accelerated mass spectroscopy (AMS) is used to measure bulk soil isotope ratios. AMS targets are prepared according to the protocol of Rutberg et al. (1996). Samples are sealed in evacuated quartz tubes with CuO, Ag, and quartz wool and are combusted at 950 °C for 2 h. The evolved CO2 can be used for target preparation and 14C analysis by AMS.

Installation, field operation, maintenance, interpretation

Soil samples for incubations, SOM stock, and SOM fraction determination should be collected from locations within the experimental plots with homogenous vegetation. In larger experimental plots, five samples, and in smaller experimental plots, at least three samples should be collected to produce one composite sample per experimental plot replicate. Samples are collected using a soil corer or auger of known diameter. The same samples can be used to determine soil bulk density (see protocol 1.3 Soil type and physical characteristics), an essential parameter to compare C stock values among soils of different texture and composition. The upper organic layer can be collected separately and samples taken at various, but well documented soil depths. In experiments with at least two samplings, one pre-treatment (or archived sample) and one post-treatment should be analysed. Soil samples should be sieved with a 2 mm mesh and dried (e.g. at 70 °C for 48 h) in a drying oven and stored dry prior to analysis. The determination of total C and N contents and δ13C and δ15N contents of bulk soil samples by elemental analysis (EA) or by EA combined with isotope ratio mass spectroscopy (EA-IRMS) can provide an initial insight into the amount of SOC present in a soil and can also be used for SOM fractionation or age determination (described in section 2.2.8.1)

In tracer studies that take advantage of C3–C4 vegetation changes, δ13C values in soil samples should be determined before and at least one year after the crop change, and changes in the isotopic composition of SOM can be used to calculate changes in SOM decomposition, see above (Balesdent & Mariotti, 1996).

Litter decomposition studies with litter differing in isotope composition (natural abundance or 13C labelled material) should, depending on the litter type (see protocols 2.2.6 Foliar litter decomposition and 2.2.7 Root decomposition), place the litter on the soil surface or bury it in the soil, after determining the δ13C values of the litter and of the soil. Soil litter mixes should be sampled at regular intervals (seasonal, annual), but should remain for at least 1 year and up to 3 years (depending on the ecosystem). After the soil samples have been collected, 13C change and incorporation into total SOM or its various fractions over time can be determined using the methodology described above (Djukic et al., 2013; Cotrufo et al., 2015; Soong & Cotrufo, 2015).

Radiocarbon data are reported in comparison to an accepted standard value of known 14C content. The most common way to express radiocarbon content of a sample is the Fraction Modern:

Fraction Modern (FM) = ((14C / 12C)sample-25) / (0.95 * (14C / 12C)common standard-19)

where the ratio of 14C to 12C has to be corrected for mass-dependent isotope fractionation to a common δ13C value of -25 ‰. The denominator refers to the primary standard for reporting radiocarbon data. The correction to a common δ13C value is necessary because radiocarbon, like 13C, is affected by mass-dependent fractionation in the environment.

For tracking bomb-produced radiocarbon in the decades since 1963, a second nomenclature is used that reports the 14C:12C ratio of the sample measured in year y to an absolute standard that does not change with time, that of the oxalic acid standard decay corrected to 1950 (Trumbore, 2009):

Δ14C = ((14C / 12C)sample-25) / (0.95 * (14C / 12C)common standard-19 e((y – 1950)/8265))) – 1) * 1000

For 14C determination it is of overall importance to avoid any potential contamination of the samples by 14C.

Where to start

Balesdent & Mariotti (1996), Cotrufo et al. (2015), Davidson & Janssens (2006), Djukic et al. (2013), Kögel-Knabner (2002), von Lützow et al. (2006), Schmidt et al. (2011), Six et al. (2002), Stewart et al. (2008), Trumbore (2009)

2.2.8.2 Special cases, emerging issues, and challenges

The guiding paradigm has been that litter mass loss corresponds to C mineralisation, neglecting that the fraction of litter that does not decay at a measurable rate (that is, mass remaining) contributes to SOM formation. Stable isotope tracing studies can be used to quantify litter-derived C and N incorporation in the mineral soil and accumulation of labile compounds and microbial products in SOM forms while mass is being lost (Cotrufo et al., 2015). A more detailed knowledge of the role of soil aggregates and of soil microbes in SOM stabilisation is needed – they are part of the SOM pool, and most of the plant-derived residues are cycled intensely within the microbial biomass (Liang et al., 2017). There is an increased notion that nutrient interactions and microbial physiology parameters should be better represented in SOC model dynamics and ecosystem models (Sierra, 2012; Cotrufo et al., 2013; Wieder, et al., 2014; Poeplau et al., 2016; Liang et al., 2017).

One of the major challenges in SOM decomposition dynamics is the spatial heterogeneity of soils. We still need a better characterisation of spatial hot-spots of SOM decomposition in soils and the rhizosphere (Herrmann et al., 2007; Mueller et al., 2013; Kaiser et al., 2015), since high labile C availability in the rhizosphere, for example, can stimulate SOM decomposition (i.e. “organic matter priming” (Fontaine et al., 2004; Kuzyakov, 2010)). We also need to characterise better the susceptibility of SOM decomposition in response to elevated CO2, changing climatic conditions, or land-use change (e.g. Harden et al., 2018). Effects of soil meso- or micro-fauna, and soil microbial biomass on SOM decomposition, have often been overlooked in field or laboratory experiments (Djukic et al., 2013; Cotrufo et al., 2015). New fingerprint techniques, such as proteomics or metabolomics, provide a whole new toolbox to characterise SOM and SOM decomposition (Keiblinger et al., 2016).

2.2.8.3 References

Theory, significance, and large datasets

Harden et al. (2018), Melillo et al. (2017), Minasny et al. (2017), Six et al. (2000)

More on methods and existing protocols

Von Lützow et al. (2006, 2007) Stewart et al. (2008), Trumbore (2009)

All references

Balesdent, J., & Mariotti, A. (1996). Measurement of soil organic matter turnover using 13C natural abundance. In T. W. Boutton, & S. Tamasaki (Eds.), Mass Spectrometry of Soils (pp. 83-111). New York: Marcel Dekker.

Batjes, N. H. (2016). Harmonized soil property values for broad-scale modelling (WISE30sec) with estimates of global soil carbon stocks. Geoderma, 269, 61–68.

Carvalhais, N., Forkel, M., Khomik, M., Bellarby, J., Jung, M., Migliavacca, M., … Reichstein, M. (2014). Global covariation of carbon turnover times with climate in terrestrial ecosystems. Nature, 514, 213-217.

Cotrufo, M. F., Wallenstein, M. D., Boot, C. M., Denef, K., & Paul, E. (2013). The Microbial Efficiency-Matrix Stabilization (MEMS) framework integrates plant litter decomposition with soil organic matter stabilization: Do labile plant inputs form stable soil organic matter? Global Change Biology, 19(4), 988-995.

Cotrufo, M. F., Soong, J. L., Horton, A. J., Campbell, E. E., Haddix, M. L., Wall, D. H., & Parton, W. J. (2015). Formation of soil organic matter via biochemical and physical pathways of litter mass loss. Nature Geoscience, 8, 776-779.

Davidson, E. A., & Janssens, I. A. (2006). Temperature sensitivity of soil carbon decomposition and feedbacks to climate change. Nature, 440(7081), 165-173.

Djukic, I., Zehetner, F., Watzinger, A., Horacek, M., & Gerzabek, M. H. (2013). In situ carbon turnover dynamics and the role of soil microorganisms therein: A climate warming study in an Alpine ecosystem. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 83(1), 112-124.

Fontaine, S., Bardoux, G., Abbadie, L., & Mariotti, A. (2004). Carbon input to soil may decrease soil carbon content. Ecology Letters, 7(4), 314-320.

Golchin, A., Oades, J., Skjemstad, J. O., & Clarke, P. (1994). Study of free and occluded particulate organic matter in soils by solid state 13C CP/MAS NMR spectroscopy and scanning electron microscopy. Australian Journal of Soil Research, 32, 285-309.

Harden, J. W., Hugelius, G., Ahlström, A., Blankinship, J. C., Bond-Lamberty, B., Lawrence, C. R., … Nave, L. E. (2018). Networking our science to characterize the state, vulnerabilities, and management opportunities of soil organic matter. Global Change Biology, 24(2), e705-e718.

Herrmann, A. M., Ritz, K., Nunan, N., Clode, P. L., Pett-Ridge, J., Kilburn, M. R., … Stockdale, E. A. (2007). Nano-scale secondary ion mass spectrometry – A new analytical tool in biogeochemistry and soil ecology: A review article. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 39(8), 1835-1850.

Kaiser, C., Kilburn, M. R., Clode, P. L., Fuchslueger, L., Koranda, M., Cliff, J. B., … Murphy, D. V. (2015). Exploring the transfer of recent plant photosynthates to soil microbes: Mycorrhizal pathway vs direct root exudation. New Phytologist, 205(4), 1537-1551.

Keiblinger, K. M., Fuchs, S., Zechmeister-Boltenstern, S., & Riedel, K. (2016). Soil and leaf litter metaproteomics – A brief guideline from sampling to understanding. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 92(11), fiw180.

Kögel-Knabner, I. (2002). The macromolecular organic composition of plant and microbial residues as inputs to soil organic matter. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 34, 139-162.

Kuzyakov, Y. (2010). Priming effects: Interactions between living and dead organic matter. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 42(9), 1363-1371.

Liang, C., Schimel, J. P., & Jastrow, J. D. (2017). The importance of anabolism in microbial control over soil carbon storage. Nature Microbiology, 2(8), 17105.

Luo, Y., Ahlström, A., Allison, S. D., Batjes, N. H., Brovkin, V., Carvalhais, N., … Zhou, T. (2016). Toward more realistic projections of soil carbon dynamics by Earth system models. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 30(1), 40–56.

Melillo, J. M., Frey, S. D., Deangelis, K. M., Werner, W. J., Bernard, M. J., Bowles, F. P., … Grandy, A. S. (2017). Long-term pattern and magnitude of soil carbon feedback to the climate system in a warming world. Science, 358, 101–105.

Minasny, B., Malone, B. P., McBratney, A. B., Angers, D. A., Arrouays, D., Chambers, A., … Winowiecki, L. (2017). Soil carbon 4 per mille. Geoderma, 292, 59–86.

Mueller, C. W., Weber, P. K., Kilburn, M. R., Hoeschen, C., Kleber, M., & Pett-Ridge, J. (2013). Advances in the analysis of biogeochemical interfaces. Nanosims to investigate soil microenvironments. Advances in Agronomy, 121, 1-46.

Poeplau, C., Herrmann, A. M., & Kätterer, T. (2016). Opposing effects of nitrogen and phosphorus on soil microbial metabolism and the implications for soil carbon storage. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 100, 83-91.

Rutberg, R. L., Schimel, D. S., Hajdas, I., & Broecker, W. S. (1996). The effect of tillage on soil organic matter using 14C: a case study. Radiocarbon, 38(2), 209-217.

Schlesinger, W. H., & Bernhardt, E. S. (2013). Biogeochemistry: An Analysis of Global Change (3rd ed.). Amsterdam: Academic Press.

Schmidt, M. W. I., Torn, M. S., Abiven, S., Dittmar, T., Guggenberger, G., Janssens, I. A., … Trumbore, S. E. (2011). Persistence of soil organic matter as an ecosystem property. Nature, 478(7367), 49-56.

Sierra, C. A. (2012). Temperature sensitivity of organic matter decomposition in the Arrhenius equation: Some theoretical considerations. Biogeochemistry, 108(1–3), 1-15.

Six, J., Elliott, E. T., & Paustian, K. (2000). Soil macroaggregate turnover and microaggregate formation: A mechanism for C sequestration under no-tillage agriculture. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 32(14), 2099–2103.

Six, J., Conant, R. T., Paul, E. A, & Paustian, K. (2002). Stabilization mechanisms of soil organic matter: Implications for C-saturation of soils. Plant and Soil, 241, 155-176.

Soong, J. L., & Cotrufo, M. F. (2015). Annual burning of a tallgrass prairie inhibits C and N cycling in soil, increasing recalcitrant pyrogenic organic matter storage while reducing N availability. Global Change Biology, 21(6), 2321-2333.

Stewart, C. E., Plante, A. F., Paustian, K., Conant, R. T., & Six, J. (2008). Soil carbon saturation: linking concept and measurable carbon pools. Soil Science Society of America Journal, 72(2), 379.

Trumbore, S. E. (2009). Radiocarbon and soil carbon dynamics. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences, 37(1), 47–66.

Trumbore, S. E., & Zheng, S. (1996). Comparison of fractionation methods for soil organic matter 14C analysis: 14C and soil dynamics : Special section. Radiocarbon, 38(2), 219-229.

von Lützow, M., Kögel-Knabner, I., Ekschmitt, K., Matzner, E., Guggenberger, G., Marschner, B., & Flessa, H. (2006). Stabilization of organic matter in temperate soils: Mechanisms and their relevance under different soil conditions – A review. European Journal of Soil Science, 57(4), 426–445.

von Lützow, M., Kögel-Knabner, I., Ekschmitt, K., Flessa, H., Guggenberger, G., Matzner, E., & Marschner, B. (2007). SOM fractionation methods: Relevance to functional pools and to stabilization mechanisms. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 39(9), 2183–2207.

Wieder, W. R., Grandy, A. S., Kallenbach, C. M., & Bonan, G. B. (2014). Integrating microbial physiology and physio-chemical principles in soils with the MIcrobial-MIneral Carbon Stabilization (MIMICS) model. Biogeosciences, 11(14), 3899-3917.

Author: Fuchslueger L1

Reviewer: Hansen K2,3, Lee H4, Schmidt IK5

Affiliations

1 Centre of Excellence PLECO (Plants and Ecosystems), Biology Department, University of Antwerp, Wilrijk, Belgium

2 Swedish Environmental Protection Agency, Stockholm, Sweden

3 Swedish Environmental Research Institute IVL, Stockholm, Sweden

4 NORCE Norwegian Research Centre and Bjerknes Centre for Climate Research, Bergen, Norway

5 Department of Geosciences and Natural Resource Management, University of Copenhagen, Frederiksberg, Denmark