Authors: Schmidt IK1, Ostonen I2 and Blume-Werry G3

Reviewer: Weigel R4

Measurement unit: g roots/soil volume or root length; Measurement scale: plot; Equipment costs: € – €€€; Running costs: €; Installation effort: medium; Maintenance effort: low to medium; Knowledge need: medium; Measurement mode: manual

A large proportion of plant biomass is located belowground, increasingly so towards the poles. For example, on a biome scale the root:shoot ratio ranges from 4.8 in tundra to 0.2 in tropical forests (Mokany et al., 2006). Besides anchoring the plants, roots also provide the plants with nutrients either through passive uptake via the mass flow of water or through active ion uptake, which requires some of the carbon allocated to roots. As much as 25–75% of the carbon assimilated by aboveground biomass (ABG) is transferred belowground and used for the production of roots, their associated rhizobiome, and respiration. About half of net assimilated C is used for respiration (Marschner, 1995; Gill & Jackson, 2000). Up to 30% may be transferred to the soil as root exudates (see protocol 2.1.5 Root exudation), and associated symbionts such as mycorrhiza also require a substantial part (see protocol 2.2.2 Root and soil colonisation by mycorrhizal fungi). Similar to the AGB, roots also have litterfall through sloughed cells, dead roots, and root exudates. Often, annual root litterfall has been equated with annual root net primary production in C budgets (Leppälammi-Kujansuu et al., 2014) but data are sparse.

The assessment of belowground biomass (BGB) provides important information on ecosystem carbon and nutrient storage and cycling but is – in contrast to AGB – difficult to assess. Accurate field-based measurements of BGB across ecosystems are needed to improve current regional-scale models for belowground carbon sequestration and carbon cycling through the turnover of fine roots. Measurements of roots are mostly very intrusive and in climate-change studies non-intrusive methods are needed to avoid destruction of the studies. Often BGB has been assessed as a fixed fraction of AGB but this relationship may change considerably along environmental gradients and in response to climate change and other global-change drivers. The measurements can be challenging as the biomass varies across the soil profile, as well as different root classes (size and orders) having different functions, plus it can be difficult to distinguish between roots of different species or if a root is dead or alive.

Although there is no consensus in the literature on how to estimate root biomass, production, and turnover most accurately (review by Addo-Danso et al., 2016), several direct and indirect methods are available to measure biomass and production of fine and coarse roots (Hendricks et al., 2006; Addo-Danso et al., 2016).

2.1.2.1 What and how to measure

- a) Root biomass

Gold standard

The most common method to assess fine-root biomass is direct harvesting of roots from soil-cores (Ostonen et al., 2005). For coarse roots, direct methods include root excavation in soil-pit, wall, or trench profiles and soil-coring. Direct excavation techniques by picking only fine roots in the field tend to underestimate fine-root biomass by about 40% due to loss of fine roots during excavation (Rosenvald et al., 2014).

Root biomass and root production from soil coring

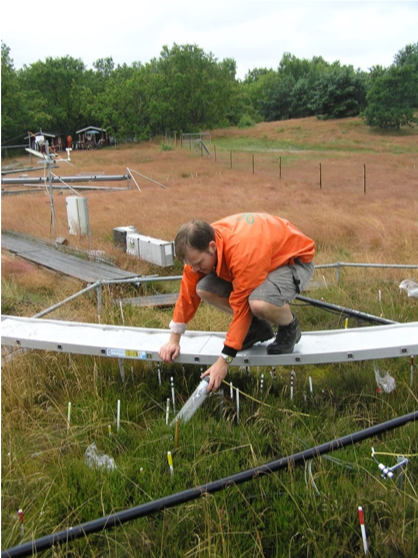

Soil coring. The most common approach determining fine-root biomass in the field is the soil coring method (see Picture 2.1.2.1) in which a soil sample is taken with a soil corer (typical diameters range from 3 to 10 cm) to the relevant depth, often the main rooting depth. It is important to measure depth and diameter of the corer for calculation of root biomass on a unit area and soil volume basis. Fine-root biomass estimates from soil cores and soil pits are closely related, and all methods should include sufficient sampling depth and sufficient replication to give robust estimates about BGB. Adequate soil sampling criteria for good estimates of BGB have been defined by Mokany et al. (2006).

Soil sampling is done with a sharp root corer (common diameter from 3 to 10 cm) from the top mineral soil down to the desired depth (e.g. 30 cm). In case there is an O-horizon, this is initially sampled on an area basis and the depth of the horizon is measured in, for example, five places.

Each soil core sample is sliced into different layers or horizons. Remember to note the depth of each layer. Soil samples for root biomass estimates can be transported in a cooler. If the roots are also used for delicate analyses as enzymatic activity or microbiome, it is recommended to use dry ice storage during field work and transportation to the laboratory. Before further processing, the adhering soil particles are washed off. Roots are separated from the soil by sieving the soil, or sorting the roots from the soil by hands or forceps, which are all laborious methods. Washing of the soil over a sieve is also possible but some of the fine roots may be lost through the sieve. Further, if the soil contains a lot of organic debris, washing or sieving is not recommended.

The root samples can be stored (at 4 °C) for shorter periods before processing or frozen fresh in soil (‑20 °C) for longer periods. The fresh root sample can be further divided into species or live and dead roots on the basis of colour, elasticity, and toughness (Persson, 1983). This is very laborious and it may not be possible to separate species, or live and dead roots on physical appearance and staining may be needed (Gregory, 2006). Finally, the roots are dried at a maximum of 70°C for 72h to constant weight (Pérez-Harguindeguy et al., 2013) and then weighed. The temperature and time for drying depend on the study question, how many samples are dried, the size, thickness and type of the plant material (e.g. large, fleshy or succulent leaves need more time) see protocol 2.1.1 Aboveground plant biomass for more details on the drying.

Root biomass from rhizotrons. In long-term manipulation experiments, destructive sampling of BGB is not possible as it will ruin the experiments within a few years and non-destructive or less intrusive sampling is required. Mini-rhizotrons enable continued assessment of (relative) root biomass.

Generally, there is no easy way of converting root length observations from mini-rhizotrons to standing root biomass. To convert root length from images to standing biomass, a conversion factor must be developed, as well as some assumptions regarding depth of view (of the scanner). A depth of view of 2 – 3 mm has been used although this is an arbitrary number. Furthermore, to upscale root length to root biomass requires an estimate of the specific root length (SRL, m g-1). This SRL should be obtained from a destructive root sampling from the site.

Bronze standard

Indirect methods are often used for assessment of belowground biomass in larger rooting systems (e.g. trees) and include modelling, size-mass allometric equations, root:shoot ratio, or Ground-Penetrating Radar (GPR); see Addo-Danso et al. (2016) for details. In a manipulation experiment, good knowledge of treatment effects on the root:shoot ratio is required.

- b) Root production

While root biomass estimates give a good indication of the belowground biomass pools in a given ecosystem, the biomass does not only include short-lived, adsorptive roots but also stable, transport roots and thus does not allow estimations on the amount of carbon that is invested into the production of new roots each year or the production of root litter. Fine-root production and turnover represent about 25% of terrestrial net primary production globally (McCormack et al., 2015). The following methods are commonly used to estimate annual production of fine roots, and each of them has their own set of advantages, disadvantages, and biases (see Table 2.1.2.1).

Table 2.1.2.1 Overview of methods to measure and estimate root biomass, production, and turnover. The table indicates destructive or non-destructive sampling approaches, sample size, and a general assessment.

| Destructive | Non-destructive | Sample size | Comments | |

| Root biomass | Soil coring | 5–10 per treatment | Soil can be used for other purposes to minimise disturbance | |

| Allometric models | Forests

Can be calibrated outside the plots |

|||

| Mini-rhizotrons | Only relative root biomass

Destructive under installation |

|||

| Root production | Sequential soil coring | 5–10 soil cores are sampled throughout the year | Simple but very destructive | |

| In-growth cores | Number depends on spatial and temporal resolution

e.g. 10 per treatment |

Hole can be re-used | ||

| Mesh | As for in-growth cores | Very destructive as the mesh is sampled after incubation by cutting 5–10 cm on each side of the mesh | ||

| Mini-rhizotrons | 5–10 mini-rhizotrons per treatment | Laborious but data on root production, phenology. Long-term studies | ||

| Root turn-over | Root biomass/root production | 5–10 soil cores | If both root biomass and production are available, the root turnover can be calculated | |

| Mini-rhizotrons | 5–10 mini-rhizotrons per treatment | Long-term studies possible | ||

| 14C radiocarbon | Expert knowledge to sample and interpret data |

Destructive methods

Sequential soil coring. A common approach of determining fine root production in the field is the sequential soil coring method (Persson, 1978; Vogt et al., 1998), where soil cores are taken repeatedly over a year. As rooting patterns are spatially variable, many replicates are needed to get good estimates on root production over time. Most commonly 5–20 samples are collected randomly or along environmental transects in a study site at intervals of about 2–6 weeks throughout a year (more frequently during the growing season). Sequential soil coring can be used for studying biomass and how roots are distributed with depth and changes over time, but as this requires many destructive samplings, the method is laborious. For Sample processing see Soil coring above.

In-growth cores. Net root productivity can be estimated by in-growth cores (Ostonen et al., 2005; Brunner et al., 2013; Arndal et al., 2018). In-growth cores are soil pits with a mesh bag or net filled with root free soil, ideally native to the site. Thus, prior to installation, a soil core is taken and roots are removed from the soil. The mesh bag with a diameter slightly larger than the soil corer is placed in the soil pit and the root free soil is filled back into the pit. The soil can be divided into depths and filled back in the same order separated with small pieces of mesh bag material. Alternatively, the soil pit can be lined with a stiff mesh material “garden mesh/netting”. A commonly used mesh size is 2 mm. The in-growth core is incubated in the soil at the same depths as the soil sampled (e.g. 0–30 cm) depending on the main rooting depth. Commonly, in-growth cores are installed vertically for practical reasons, but an angled installation may be more suitable depending on root architecture (Milchunas, 2009).

During harvesting, roots outside the bag are removed with scissors after which roots from the bag can be picked with forceps and washed. The harvesting frequency is biome and plant species or community specific. In boreal forests and sub-arctic regions, where annual root production is low, the in-growth cores should be harvested for at least two or three consecutive years and 2–3 times a year for annual production (Makkonen & Helmisaari, 1999; Ostonen et al., 2005). However, in the tropics and temperate ecosystems, and for pioneer plant (tree) species, shorter time periods are appropriate. After the first harvest, the root-free soil may be replaced in the pit and a subsequent harvest can take place. Installation in early spring and late autumn will enable assessment of root production in winter and in the growing season, but species- and biome-specific differences have to be taken into account to avoid underestimation. In-growth cores require more preparation time than sequential soil coring, but give more accurate estimates of root production over time. As the root-free core needs to be re-colonised, there is a risk of under- or over-estimating root production depending on root competition, and in-growth cores generally give a lower estimate of root production than mini-rhizotrons and isotope turnover methods (Milchunas, 2009). This risk can be reduced by using smaller diameter cores and more replicates. For example, Laiho et al. (2014) showed that 10–30 cores (with a diameter of 3.18 cm) were needed to get robust estimations of root production in peatland forests and a fen. In manipulation experiments, the relative root production rate may be sufficient. For Sample processing see Soil coring above.

Root in-growth mesh (called also nets, sheets, screens)

Measurements of root production by sequential soil coring, root imaging (see below), or by in-growth cores are time and labour intensive, have a high degree of uncertainty, and can induce changes in the chemical and physical properties of the soil. The root in-growth mesh method has been proposed as an alternative technique to overcome these problems (Fahey & Hughes, 1994; Jentschke et al., 2001; Godbold et al., 2003). Using this technique, root production is estimated by placing a mesh (for example 7–10 cm x 20–40 cm, 1–2 mm mesh size) vertically into the soil for a specific period of time and then measuring the number and weight of roots that grow through the mesh (Hirano et al., 2009). The procedure is much easier than other methods, requires only simple equipment, and causes minimal soil disturbance (Godbold et al., 2003). The method has been discussed by Ohashi et al. (2016) and Montagnoli et al. (2014).

The root nets (preferably 15–30 per sampling time) are extracted from soil as 10 x 10 cm soil blocks (Lukac & Godbold, 2010) annually at the end of every vegetation period. Extracted nets are washed free of soil in the lab, and fine roots grown through the mesh are counted and cut to 1 cm on both sides of the net to create a ‘virtual’ 2 cm thick core. Roots are removed from the net and different plant species can be separated if visually distinguishable, although only living roots can be estimated by this method.

Several methods exist to calculate fine-root production from the change in the fine-root biomass and necromass data. The “Maximum-Minimum” method calculates the annual fine-root production by subtracting the lowest biomass from the highest biomass value irrespective of other biomass values recorded during a full year (McClaugherty et al., 1982). The “Decision Matrix” method calculates the annual fine-root production by balancing the living and dead root biomass compartments and summing all calculated productions between each pair of consecutive sampling dates throughout a full year (Fairley & Alexander, 1985).

Non-destructive methods

Root imaging: Mini-rhizotrons, flatbed scanners, smartphone solutions. The most common technique based on direct observations of root growth dynamics in situ is the mini-rhizotron method (see Picture 2.1.2.2), although there are also root windows, rhizotrons, and flatbed scanner or smartphone imaging methods in use. All methods enable following root growth dynamics and phenology from birth to death of the finest, ephemeral, and distal roots (as reviewed in Hendrick & Pregitzer, 1996; Johnson et al., 2001; Rewald & Ephrath, 2013; Mohamed et al., 2017).

First stage is the installation of permanent transparent tubes of c. 5–7 cm in diameter (mini-rhizotron) or boxes for flatbed scanners or smartphone cameras into the soil (Mohamed et al., 2017), or root windows that are soil profiles covered by transparent plexiglass plates (Stober et al., 2000).

Mini-rhizotron installation is usually done using an angled guide and soil corer (Johnson et al., 2001, Rewald & Ephrath, 2013). This is typically at a 45 ° angle (for observations at different depths while ensuring good capture of vertical and horizontal rooting systems) or horizontally (for more detailed observations at a certain depth of interest; Smucker, 1993). After installation, some time has to pass before the first measurements to allow the vegetation to recover from the disturbance. The time needed depends on the natural stability of the system and species present, but an inactivity phase of 6–12 months is common (Rewald & Ephrath, 2013).

For root imaging, a tube-fitting camera or scanner is inserted into the tube to take pictures of the tube-soil interface (about 3 mm space behind the tube class), where the roots grow. By repeatedly taking pictures of the same spot (ensured by an indexing handle on the camera system), root production and mortality over time can be measured. A crucial aspect is to choose the time interval between these measurements, as there is a trade-off between availability of time and resources and measurement accuracy (Johnson et al., 2001). Long sampling intervals can underestimate root production, as roots can grow and die off between sampling events, and, in general, relatively shorter intervals should be used for more productive systems. Most studies use intervals of 2–4 weeks: using intervals of < 3 weeks did not underestimate root production in five different ecosystems (Balogianni et al., 2016).

Sample processing: The method is very labour intensive. Currently, the images of the roots have to be analysed manually by mapping all roots, usually using specific software (WinRhizotron (Regent Inc), Rootfly (Clemson University, free software), RootSnap (CID BioScience, free software), etc).

Mini-rhizotrons are an excellent tool to measure timing of root production and mortality (root phenology), and are often used for estimating root longevity and turnover. However, they are not the best method to estimate root biomass, as they only offer a two-dimensional view into the soil. Several conversion methods exist that use mini-rhizotron data to infer root biomass: see Metcalfe et al. (2007) for a comparison of different methods.

Turnover rate

The term turnover rate of a certain root category means the rate that root biomass is replaced during a year. Fine-root turnover rate is dependent on the fine-root biomass and the annual production of fine roots, but also on the various methods and calculations (Brunner et al., 2013). The mean lifespan can be calculated by dividing the “pool” (biomass) by its “input” (annual production). Because the turnover rate is the inverse of lifespan, it can be calculated by dividing the “annual production” by the “root standing biomass” (Gill & Jackson, 2000), which most commonly means an average root biomass, but there are several studies using maximum root biomass instead. According to Brunner et al. (2013), however, using maximum fine-root biomass to calculate the fine turnover rate, results in about 30% higher values of root turnover. To decrease the lab intensity, a combined method has been proposed – fine-root turnover rate is calculated from in-growth cores/sheets and multiplied by fine-root biomass estimated from soil cores (Ostonen et al., 2005; Löhmus & Ostonen, 2006).

With mini-rhizotrons, individual roots can be observed from birth to death for estimations of root longevity. However, this is difficult for ecosystems with long-lived roots or systems with a lot of soil movement (e.g. freeze-thaw or drying and re-wetting of soils). Similarly to destructive methods, turnover rate can also be calculated with mini-rhizotrons by using the observed root growth and total root length density.

Radiocarbon (14C) content has been used to estimate fine-root productivity and fine-root turnover (Gaudinski et al., 2001) using the fallout 14C signal from nuclear weapons testing in the 1950s and 1960s. The method requires good knowledge and sampling of roots of known age.

Where to start

Addo-Danso et al. (2016), Mancuso (2012), Rewald & Ephrath (2013), Smit et al. (2014)

2.1.2.2 Special cases, emerging issues, and challenges

15N assay. Nitrogen deficiency can be assessed in fresh roots using a 15N labelling assay (Jones et al., 1991). The roots are placed in a 15N solution on the same day as harvesting and 15N uptake in the roots can be measured with mass spectrometry. The assay with excised roots represents a relative measurement of the root net uptake capacity and not the actual uptake rate, as would have been found with the roots still attached to the plant (Göransson et al., 2007). High 15N uptake demonstrates nitrogen limitation (Jones et al., 1991; Michelsen et al., 1995; Arndal et al., 2014).

The N-deficiency bioassay follows the procedure of Jones et al. (1991). Using roots from in-growth cores, the root material will be relatively homogeneous and with a maximum age similar to the time the in-growth cores have been in the soil.

Roots are sorted by hand and fine roots washed in demineralised water. The roots are stored in a plastic bag and kept in the dark at 5 °C until the assay is conducted (best the same day as sorting).

The fresh root bundles are marked with a name tag and pre-soaked for 30 min in 5 x 10-4 M CaCl2 solution) to maintain root cell-membrane integrity and to remove ammonium and nitrate from the cell-free space. After the pre-treatment, the roots are transferred to 5 x 10-4 M CaCI2 containing 15NH4Cl (20% enrichment; 2 ml 15NH4Cl and 8 ml 14NH4Cl). They are left in the solution for 2 h, washed for 15 min in running demineralised water, dried in a paper bag, weighed, and finely cut.

Analysis of 15N excess

Samples of about 12 mg root are analysed on a mass spectrometer. Excess 15N (atom %) can be converted to absorption rate of N (mgN g-1 rootDW 2 h-1). The total N in the roots can be calculated, after subtraction of N which had been taken up during the bioassay (Michelsen et al., 1995).

Root:shoot ratio

Due to the destructive nature of root sampling, AGB is often used as a rough estimate of BGB. A fixed belowground:aboveground ratio is typically applied to estimate BGB from AGB (see review in Addo-Danso et al., 2016), although a meta-analysis of global data shows this to be a questionable approach (see Mokany et al., 2006) as the functional relationship between the aboveground and belowground parts of the vegetation may change due to climatic factors, for example drought or elevation, and CO2 may increase the R:S ratio due to water or nutrient limitation, respectively.

A number of studies report on the functional relationship between AGB and BGB, for example the needles:fine-root ratio (Helmisaari et al., 2009). Absorptive fine-root biomass (aFRB) per stand basal area (BA) (aFRB/BA, kg m-2) has been used as a proxy to describe the functional relationship between the aboveground and belowground parts of a forest stand (Ostonen et al., 2011, 2017) and the use of vegetation-specific root:shoot ratios were found to be a more accurate method for predicting root biomass (Mokany et al., 2006).

Sample size and sample depth

The issue of sample volume is complicated and the same method may not be suitable for both fine and coarse roots. Different methods vary by more than an order of magnitude with respect to soil volume sampled (Taylor et al., 2013). Adequate soil sampling criteria for good estimates of BGB in a certain area have been defined by Mokany et al. (2006) as follows: the depth of root sampling has to be > 75 cm for deserts and very arid ecosystems, > 50 cm for woodlands, savannahs, shrublands, temperate and tropical forests, > 30 cm for grasslands and boreal forests, and > 20 cm for tundra. As for replication, they recommend > 10 soil cores of 5 cm diameter; > 3 soil pits 50 cm long by 50 cm wide; and entire root systems excavated for > 3 woody plants. However, the amount of replicates should also take into account how spatially variable the vegetation is, i.e. tussock tundra or shrublands may need more replicates than homogenous grasslands. In reality, few studies meet these criteria.

Upscaling

It is important to measure depth and diameter of the corer for calculation of root biomass on a unit area and soil volume basis.

2.1.2.3 References

Theory, significance, and large datasets

Freschet & Roumet (2017), Iversen et al. (2017): FRED (Fine Root Ecology Database), McCormack et al. (2015)

More on methods and existing protocols

Smit et al. (2014)

All references

Addo-Danso, S. D., Prescott, C. E., & Smith, A. R. (2016). Methods for estimating root biomass and production in forest and woodland ecosystem carbon studies: A review. Forest Ecology and Management, 359, 332-351.

Arndal, M. F., Schmidt, I. K., Kongstad, J., Beier, C., & Michelsen, A. (2014). Root growth and N dynamics in responses to multi-year experimental warming, summer drought, and elevated CO2 in a mixed heathland-grass ecosystem. Functional Plant Biology, 41, 1-10.

Arndal, M. F., Tolver, A., Larsen, K. S., Beier, C., & Schmidt, I. K. (2018). Root growth and vertical distribution in response to elevated CO2, warming and drought in a mixed heathland-grassland. Ecosystems, 21, 15-30.

Balogianni, V., Blume-Werry, G., & Wilson, S. D. (2016). Root production in contrasting ecosystems: the impact of rhizotron sampling frequency. Plant Ecology, 217, 1359-1367.

Brunner, I., Bakker, M. R., Björk, R. G., Hirano, Y., Lukac, M., Aranda, X. … Ostonen, I. (2013). Fine-root turnover rates of European forests revisited: an analysis of data from sequential coring and ingrowth cores. Plant and Soil, 362(1-2), 357-372.

Fahey, T. J., & Hughes, J.W. (1994). Fine root dynamics in a northern hardwood forest ecosystem, Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest, NH. Journal of Ecology, 82, 533-548.

Fairley, R. I., & Alexander, I. J. (1985). Methods of calculating fine root production in forests. In A. H. Fitter, D. Atkinson, & D. J. Read (Eds.), Ecological Interactions in Soil: Plants, Microbes and Animals. (pp. 37-42). Oxford: Blackwell.

Freschet, G.T., & Roumet, C. (2017). Sampling roots to capture plant and soil functions. Functional Ecology, 31(8), 1506-1518.

Gaudinski, J. B., Trumbore, S. E., Davidson, E. A., Cook, A. C., Makrewitz, D., & Richter, D. D. (2001) The age of fine-root carbon in three forests of the eastern United States measured by radiocarbon. Oecologia, 129, 420-429.

Gill, R. A., & Jackson, R. B. (2000). Global patterns of root turnover for terrestrial ecosystems. New Phytologist, 147, 13-31.

Godbold, D. L., Fritz, H. W., Jentschke, G., Meesenburg, H., & Rademacher, P. (2003). Root turnover and root necromass accumulation of Norway spruce (Picea abies) are affected by soil acidity. Tree Physiology, 23, 915-921.

Göransson, H., Fransson, A. M., & Jonsson-Belyazid, U. (2007). Do oaks have different strategies for uptake of N, K and P depending on soil depth? Plant and Soil, 297, 119-125.

Gregory, P. J. (2006). Plant Roots: Growth, Activity and Interaction with Soils. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Helmisaari, H. S., Ostonen, I., Löhmus, K., Derome, J., Lindroos, A. J., Merilä, P., & Nöjd, P. (2009). Ectomycorrhizal root tips in relation to site and stand characteristics in Norway spruce and Scots pine stands in boreal forests. Tree Physiology, 29, 445-456.

Hendrick, R. L., & Pregitzer, K. S. (1996). Applications of minirhizotrons to understand root function in forests and other ecosystems. Plant and Soil, 185(2), 293-304.

Hendricks, J. J., Hendrick, R. L., Wilson, C. A., Mitchell, R. J., Pecot, S. D., & Guo, D. (2006). Assessing the patterns and controls of fine root dynamics: an empirical test and methodological review. Journal of Ecology, 94, 40-57.

Hirano, Y., Noguchi, K., Ohashi, M., Hishi, T., Makita, N., Fujii, S., & Finér, L. (2009). A new method for placing and lifting root meshes for estimating fine root production in forest ecosystems. Plant Root, 3, 26-31.

Iversen, C. M., McCormack, M. L., Powell, A. S., Blackwood, C. B., Freschet, G. T., Kattge, J., … Violle, C. (2017). A global Fine-Root Ecology Database to address belowground challenges in plant ecology. New Phytologist, 215, 15-26.

Jentschke, G., Drexhage, M., Fritz, H. W., Fritz, E., Schella, B., Lee, D. H., … Godbold, D. L. (2001). Does soil acidity reduce subsoil rooting in Norway spruce (Picea abies)? Plant Soil, 237, 91-108.

Johnson, M. G., Tingey, D. T., Phillips, D. L., & Storm, M. J. (2001). Advancing fine root research with minirhizotrons. Environmental and Experimental Botany, 45, 263-289.

Jones, H. E., Quarmby, C., & Harrison, A. F. (1991). A root bioassay test for nitrogen deficiency in forest trees. Forest Ecology and Management, 42, 267-282.

Laiho, R., Bhuiyan, R., Straková, P., Mäkiranta, P., Badorek, T., & Penttilä, T. (2014). Modified ingrowth core method plus infrared calibration models for estimating fine root production in peatlands. Plant and Soil, 385, 311-327.

Leppälammi-Kujansuu, J., Aro, L., Salemaa, M., Hansson, K., Kleja, D. B., & Helmisaari, H.-S. (2014). Fine root longevity and carbon input into soil from below- and aboveground litter in climatically contrasting forests. Forest Ecology and Management, 326, 79-90.

Löhmus, K., & Ostonen, I. (2006). Combined method of ingrowth and soil cores to estimate fine root production Method Sheets. In J. Luster & R. Finlay (Eds.), Handbook of Methods used in Rhizosphere Research, Birmensdorf: WSL

Lukac, M., & Godbold, D. L. (2010). Fine root biomass and turnover in southern taiga estimated by root inclusion nets. Plant Soil, 331, 505-513.

Makkonen, K., & Helmisaari, H. S. (1999). Assessing fine-root biomass and production in a Scots pine stand—comparison of soil core and root ingrowth core methods. Plant Soil, 210, 43-50.

Mancuso, S. (Ed.) (2012). Measuring Roots: An Updated Approach. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

Marschner, H. (1995). Mineral Nutrition of Higher Plants (2nd ed.). London: Academic Press.

McClaugherty, C. A., Aber, J. D., & Melillo, J. M. (1982). The role of fine roots in the organic-matter and nitrogen budgets of two forested ecosystems. Ecology, 63, 1481-1490.

McCormack, M. L., Dickie, I. A., Eissenstat, D. M., Fahey, T. J., Fernandez, C. W., Guo, D., … Zadworny, M. (2015). Redefining fine roots improves understanding of below-ground contributions to terrestrial biosphere processes. New Phytologist, 207, 505-518.

Metcalfe, D. B., Meir, P., & Williams, M. (2007). A comparison of methods for converting rhizotron root length measurements into estimates of root mass production per unit ground area. Plant and Soil, 301, 279-288.

Michelsen, A., Schmidt, I. K., Jonasson, S., Dighton, J., Jones, H. E., & Callaghan, T. V. (1995). Inhibition of growth, and effects on nutrient uptake of arctic graminoids by leaf extracts – allelopathy or resource competition between plants and microbes? Oecologia, 103, 407-418.

Milchunas, D. G., (2009). Estimating root production: comparison of 11 methods in shortgrass steppe and review of biases. Ecosystems, 12, 3181-1402.

Mohamed, A., Monnier, Y., Mao, M., Lobet, G., Maeght, J.-L., Ramel, M., & Stokes, A. (2017). An evaluation of inexpensive methods for root image acquisition when using rhizotrons. Plant Methods, 13, 11.

Mokany, K., Raison, R. J. & Prokushkin, A. S. (2006). Critical analysis of root:shoot ratios in terrestrial biomes. Global Change Biology, 12, 84-96.

Montagnoli, A., Terzaghi, M., Scippa, G. S., & Chiatante, D. (2014). Heterorhizy can lead to underestimation of fine-root production when using mesh-based techniques. Acta Oecologica, 59, 84-90.

Ohashi, M., Nakano, A., Hirano, Y., Noguchi, K., Ikeno, H., Fukae, R., … Finér, L. (2016). Applicability of the net sheet method for estimating fine root production in forest ecosystems. Trees, 30(2), 571-578.

Ostonen, I., Löhmus, K., & Pajuste, K. (2005). Fine root biomass, production and its proportion of NPP in a fertile middle-aged Norway spruce forest: comparison of soil core and ingrowth core methods. Forest Ecology and Management, 21, 264-277.

Ostonen, I., Helmisaari, H.-S., Borken, W., Tedersoo, L., Kukumägi, M., Bahram, M., … Löhmus, K. (2011). Fine root foraging strategies in Norway spruce forests across a European climate gradient. Global Change Biology, 17, 3620-3632.

Ostonen, I., Truu, M., Helmisaari, H.-S., Lukac, M., Borken, W., Vanguelova, E., … Truu, J. (2017). Adaptive root foraging strategies along a boreal-temperate forest gradient. New Phytologist, 215, 977-991.

Pérez-Harguindeguy, N., Díaz, S., Garnier, E., Lavorel, S., Poorter, H., Jaureguiberry, P., … Cornelissen, J. H. C. (2013). New handbook for standardised measurement of plant functional traits worldwide. Australian Journal of Botany, 61(3), 167-234.

Persson, H. A. (1978). Root dynamics in a young Scots pine stand in Central Sweden. Oikos, 30, 508-519.

Persson, H. A. (1983). The distribution and productivity of fine roots in boreal forests. Plant Soil, 71, 87-101.

Rewald, B., & Ephrath, J. E. (2013). Mini-rhizotron techniques. In A. Eshel, & T. Beeckman (Eds.), Plant Roots: The hidden half (4th ed., pp. 1-15). New York: CRC Press.

Rosenvald, K., Tullus, A., Ostonen, I., Uri, V., Kupper, P., Aosaar, J., … Löhmus, K. (2014). The effect of elevated air humidity on young silver birch and hybrid aspen biomass allocation and accumulation – Acclimation mechanisms and capacity. Forest Ecology and Management, 330, 252-260.

Smit, A. L., Bengough, A. G., Engels, C., van Noordwijk, M., Pellerin, S., & van de Geijn, S. C. (2014). Root Methods: A Handbook. Springer Science & Business Media.

Smucker, A. J. M. (1993). Soil environmental modifications of root dynamics and measurement. Annual Review of Phytopathology, 31, 191-216.

Stober, C., George, E., & Persson, H. A. (2000). Root growth and response to nitrogen. In E. D. Schulze (Ed.), Carbon and Nitrogen Cycling in European Forest Ecosystems (pp. 99-121). Berlin: Springer.

Taylor, B. N., Beidler, K. V., Cooper, E. R., Strand, A. E., & Pritchard, S. G. (2013). Sampling volume in root studies: the pitfalls of under-sampling exposed using accumulation curves. Ecology Letters, 16, 862-869.

Vogt, K. A., Vogt, D. J., & Bloomfield, J. (1998). Analysis of some direct and indirect methods for estimating root biomass and production of forest at ecosystem level. Plant Soil, 200, 71-89.

Authors: Schmidt IK1, Ostonen I2 and Blume-Werry G3

Reviewer: Weigel R4

Affiliations

1 Department of Geosciences and Natural Resource Management, University of Copenhagen, Frederiksberg, Denmark

2 Institute of Ecology and Earth Sciences, University of Tartu, Tartu, Estonia

3 Experimental Plant Ecology, Institute of Botany and Landscape Ecology, University of Greifswald, Germany

4 Plant Ecology, Albrecht-von-Haller Institute for Plant Sciences, University of Goettingen, Goettingen, Germany

Pingback:Aboveground plant biomass – ClimEx Handbook