Authors: Ostonen, I1, Ven, A2, Meier IC3

Reviewer: Preece, C4

Measurement unit: minutes, hours, days; Measurement scale: length, mass or surface unit of root; ground unit of a plot or site; Equipment costs: €-€€€; Running costs: €-€€€; Installation effort: high; Maintenance effort: low to high (frequent recording); Knowledge need: medium to high (species knowledge at the root level); Measurement mode: manual

Root exudation is part of rhizodeposition and a source of soluble organic carbon (C) released by plant roots to the soil. Root exudates are easily-degradable, low molecular weight organic (LMWO) substances that influence the size and sink strength of soil organic matter (SOM), since (i) they are preferentially used by soil microbes as substrate, which stimulates these microbes to also decompose less bioavailable soil organic C via a priming effect (Kuzyakov et al., 2000; Phillips et al., 2011, 2012; Meier et al., 2017), (ii) they are a chemical signal for symbiosis with mycorrhizal fungi which increase the accessibility of nutrients, (iii) they induce enzymatic degradation of SOM, and (iv) they increase soil aggregation. Exudates can be released passively due to the concentration gradient between root cells and soil solution, but they can also be secreted actively (e.g. via anion channels and vesicle transport) in response to metal toxicity, nutrient stress, the occurrence of plant and microbial taxa, and other environmental factors (Marschner, 1995; Jones et al., 2004; Bais et al., 2006; Canarini et al., 2019). The major components of root exudates are organic acids, carbohydrates, amino acids, and phenolics (Neumann & Römheld, 2007). The C release via root exudation is supposed to represent between 1 and 10% of the net assimilated C (Grayston et al., 1997; Jones et al., 2004), but may increase to up to 30% with drought (Liese et al., 2018). Under climate change, enhanced significance is attributed to root exudation, as the inducement of microbial priming effects by increased root C exudation is assumed to delay progressive N limitation (sensu Progressive N Limitation hypothesis; Luo et al., 2004) in forests exposed to elevated CO2.

Methods for the collection of root exudates have developed along two main trajectories: a (semi‑)artificial experimental trajectory that attempts to have sterile collection conditions for the understanding of mechanisms, and an in situ ecological trajectory that attempts to cover the natural complexity of root-rhizosphere interactions, for example in mature forests, and obtains the most representative exudation pattern. In the context of climate-change ecology and other global-change drivers, the in situ methods are of greater importance and, thus, we focus our review on these methods only. The described methods are applicable for site-based studies in the field, along environmental gradients in natural landscapes or with modified land-use or nutritional status, as well as in climate-change manipulation studies including pot experiments in a greenhouse and/or chambers. For an overview of laboratory methods the reader is referred to the literature (e.g. Luster & Finlay, 2006; Neumann & Römheld, 2007; Vranova et al., 2013; Oburger & Schmidt, 2016).

2.1.5.1 What and how to measure?

- a) In situ root exudate collection

Culture-based cuvette method. The collection of total root exudation can be conducted with the culture-based cuvette method, which is a modification of hydroponic sampling and was adapted by Phillips et al. (2008) for field use. However, the method can be used in non-sterile greenhouse and climate chamber experiments (Gargallo-Garriga et al., 2018). In contrast to hydroponic sampling, the sampled fine root systems (terminal fine root systems < 2 mm in diameter with laterals) grow in soil and remain attached to the plant during the whole sampling process. Extraction of the fine root systems from soil has to be extremely carefully conducted to maintain the integrity of the (mycorrhizal) root system as much as possible. For this purpose, the root systems are excavated with soft brushes and fine forceps from the wall of a small soil pit and the soil particles adhering to the root system are carefully removed using deionised water, 0.5 mM CaCl2, or autoclaved dilute nutrient solution. At this point of the sampling process, the species identity of the root system has to be confirmed with a morphological key (or by tracking the root system back to the mother tree). The root systems are placed overnight in moist, sandy soil to allow recovery from the excavation stress. On the next day, the soil-free and cleaned intact root systems are placed into a sterile cuvette (preferentially a glass syringe or alternatively a plastic syringe from which the plunger is removed), back-filled with sterile glass beads (≤ 2 mm in diameter) that provide the mechanical impedance and porosity of soils, and moistened with sterile, dilute nutrient solution (see 2.1.5.2 Special cases, emerging issues, and challenges below for a discussion of the culture medium). The cuvette is closed with a rubber septum and covered by plastic paraffin film, while ensuring the integrity of the emerging root. Sterile cuvettes with glass beads and culture medium (i.e. without roots) are treated similarly and included as controls. The experimental set-up is covered, for example by leaves from the litter layer to dampen temperature differences to the surrounding soil, and roots are allowed to equilibrate in the cuvette environment for 48 h. Subsequently, cuvettes are cleaned by being flushed 3 to 5 times with the culture medium using a low-pressure vacuum. New culture medium is added and the root systems are equilibrated for a sufficient time period (see 2.1.5.2 Special cases, emerging issues, and challenges below for a discussion of the incubation time). After the incubation period, the trap solutions containing exudates are collected from each cuvette, filtered immediately through a sterile 0.22 μm syringe filter, and kept cool for transport to the lab, where they are either analysed immediately or are concentrated by freeze-drying and stored at -20 °C for later analyses.

Basic analyses include the measurement of the concentration of the dissolved organic C in the trap solution using a total organic carbon (TOC) analyser and weighing of the dried root system. Net mass-specific exudation rates (gross root exudation minus reabsorption and microbial consumption) are then calculated as the total amount of C flushed from each root system over the incubation period divided by the total root mass and incubation time (mmol C g-1 h-1). Advanced analyses include the identification of the exuded metabolites by ecometabolomics and the morphological and architectural analyses of the root system by optical surface area measurement. While the cuvette method allows the collection and compositional analysis of root exudates from mature trees in their natural environment and therefore is the method that is the closest to investigating the natural exudate composition and exudation patterns of mature trees, it has to be kept in mind that they may still differ from their original pattern since root exudates are sampled in a medium that differs from a natural soil environment (e.g. with respect to nutrient availability, aeration, and the interaction with soil microbes).

Measurement unit: hours; Measurement scale: length, mass or surface unit of root; ground unit of a plot or site; Equipment costs: €; Running costs: €-€€€ (according to the chemical analysis); Installation effort: high; Maintenance effort: high (frequent cleaning and long exposure time); Knowledge need: medium (species knowledge at the root level); Measurement mode: manual

Sampling with filter papers or agar sheets. The collection of specific exuded compounds can be conducted by the application of filter papers, agar sheets, or resin foils to excised root systems. Similar to the culture-based cuvette method (see the description of the Culture-based cuvette method above), the sampled fine root systems are carefully excavated from the soil and remain attached to the plant during the whole sampling process. After excavation, the species identity of the root system has to be confirmed with a morphological key (or by tracking the root system back to the parent tree). Filter paper with high soaking capacity is cut into an appropriate size, washed with methanol and distilled water to remove impurities, and applied to the root zones of interest for short time periods (1–3 h; Luster & Finlay, 2006). During this time, the rest of the root system has to be covered with moist filter paper soaked in nutrient solution to avoid drying. The LMWO compounds absorbed by the filter paper (or phenolic compounds by cellulose acetate filters, enzymes by blotting membranes) are re-extracted with water or buffer (according to subsequent analyses), the solution is centrifuged, and the supernatant used for chemical compound or enzymatic analyses. Alternatively, the filter paper can be soaked with artificial substrates for enzymes, which are visualised after colour reaction (Figure 2.1.5.1).

Agar gels have been used as a carrier matrix for Al-aluminium complexes that visualise the exudation of Al-complexing chelators (Luster & Finlay, 2006). The gel sheets are produced in small thicknesses and are applied until discoloration becomes visible. Similarly, the exudation of reducing exudates (e.g. malate, phenolics) for the reduction of Fe-III-oxides can be visualised by the application of agar gels containing Fe redox indicators. Common to all three methods, i.e. sampling with filter papers, agar sheets, or resin foils, is that they allow the analysis of spatial variation of exudation rates along the root axis, but are restricted to specific compounds or compound classes, which are bound by the media, and to small sampling volumes. Consequently, these methods allow only qualitative or semi-quantitative comparison of compounds (e.g. Shi et al., 2011).

Measurement unit: hours; Measurement scale: ground unit of a plot or site; Equipment cost: €; Running costs: €; Installation effort: high; Maintenance effort: low; Knowledge need: medium (species knowledge at the root level); Measurement mode: manual

- b) Rhizosoil solution sampling

Micro-suction cups. Rhizosoil solution – root exudation minus re-absorption, microbial consumption, and soil matrix adsorption – can be collected with the help of micro-suction cups. This technique allows non-destructive and repeated in situ collection of rhizosoil pore water sampling at high spatial resolution (scale µL mm-1) (Puschenreiter et al., 2005; Dessureault-Rompré et al., 2006). To access the root systems in their undisturbed soil environment an even, flat soil surface has to be experimentally manufactured (e.g. by the installation of soil observation windows or rhizoboxes) a sufficient time period before the collection campaign to ensure new root ingrowth. According to the dynamic of the investigated root systems, installation of these root windows may require one or several years lead time before the actual solution collection can take place. Each micro-suction cup consists of a small diameter, porous tip (with a pore size <0.2 µm that excludes microbial invasion into the samplers) and a tube with a luer lock to connect to vacuum tubes or syringes. The material of the tips is critical as it may induce material-dependent artefacts, i.e. retention of specific compounds. For the installation of the delicate micro-suction cups, a small hole slightly smaller in diameter than the cup diameter (1–2.5 mm) is drilled close to the root segment of interest and the micro-suction cup is carefully pushed with its porous part into the rhizosoil. Any remaining soil holes or loose soil contact are equalised with local soil or soil slurry. The micro-suction cup is connected to a low-pressure vacuum which is applied either via a vacuum pump or a syringe (Figure 2.1.5.2). The retrieved sampling volume is typically very small and the yield of several micro-suction cups may have to be combined for a sufficient volume for later analysis.

For a temporal resolution, micro-suction cups can be repeatedly sampled over a longer time period, but each sampling should alternate with sampling-free equilibration periods, since the sampling of rhizosoil solution imposes changes to the soil moisture and chemical conditions in the rhizosoil (Vetterlein & Jahn, 2004). For high spatial resolution, micro-suction cups are located in close, but different distances to the root segment of interest or along the root. In extremely dry or clay-rich soil environments, irrigation of the soil from the top can be required to ensure sufficient soil solution for the extraction, but dilutes the rhizosoil solution. The extracted rhizosoil solution can be analysed for dissolved organic C, dissolved gases, and for its elemental composition. A major disadvantage of this method is that both adsorption to the soil matrix and microbial degradation change the exudate composition and concentration and thus quantification of root exudation is not possible.

Measurement unit: days; Measurement scale: plot; Equipment costs: €€; Running costs: €; Installation effort: high; Maintenance effort: high (frequent recording); Knowledge need: medium (species knowledge at the root level); Measurement mode: manual

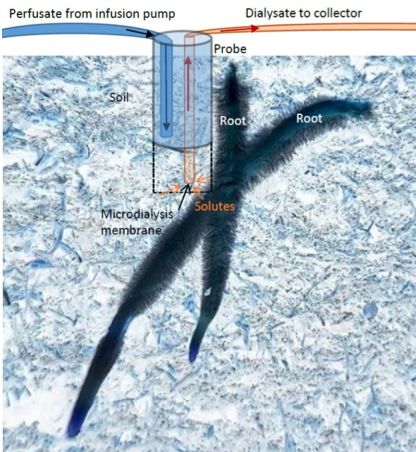

Micro-dialysis. Micro-dialysis has been introduced as a novel method to sample diffusive fluxes of metals (Miró et al., 2010) and N species from soil (Inselsbacher et al., 2011; Shaw et al., 2014; Brackin et al., 2017). Micro-dialysis is a membrane-based technique for monitoring freely available nutrients and ions in the soil at the root scale. The method is based on the passive diffusion of solutes from rhizosoil across a hydrophilic semipermeable membrane at the end of the probe into a sample collector, while remaining sterile and without the breakdown by microbes or enzymes, which are excluded by the small aperture size of the probes (20 kDa). This means that organic forms of nitrogen (such as amino acids), for example, remain intact (Inselsbacher et al., 2011; Brackin et al., 2015). The micro-dialysis probe i

s connected to the (syringe) pumping system that pushes water (or any other perfusion liquid (see Miró et al., 2010) through the tubing to the probes in the soil and onto safe-lock vials within the fraction collector (Figure 2.1.5.3; Brackin et al., 2017).

Further details of a probe construction and perfusate flow rate delivery are available in Miró & Frenzel (2004). The miniature design of the probes enables installation with minimal disturbance and high spatial resolution. Micro-dialysis can be used repeatedly over time, removes only dissolved compounds but not soil water, and preserves nutrients in their native form (Miró & Frenzel, 2005; Inselsbacher et al., 2011). Even though accurate calibration and deduction of external soil solution concentrations is problematic (Shaw et al., 2014), the micro-dialysis method avoids biases common to the suction-cup method, such as adsorption to soil particles and dependence on soil pore sizes.

Measurement unit: minutes to hours; Measurement scale: ground unit of a plot or site; Equipment costs: €€; Running costs: €-€€€ (according to the chemical analysis); Installation effort: high; Maintenance effort: high (frequent recording); Knowledge need: medium (species knowledge at the root level); Measurement mode: manual

- c) Plant–microbe Interactions

Stable isotope enrichment. Isotope labelling with 13C or 14C is used to trace the partitioning and fate of assimilated C in plants and soil. This method estimates total rhizodeposition, i.e. the release of root cap and border cells, insoluble mucilage, soluble root exudates, volatile organic C, the C flux to mycorrhizae, and the death and lysis of root cells (Jones et al., 2009). For in situ isotope labelling, safety regulations restrict the use of C isotopes to the stable 13C. Labelling can be conducted as a pulse, which can be repeated several times during the growing season (Whipps, 1990; Kuzyakov, 2001), or can be conducted continuously, which is more expensive, but results in constant isotopic ratios in all metabolites. The latter is more appropriate for the estimation of the total amount of C transferred from plants to soil (Ge et al., 2015). The separation between root-derived C and soil organic matter C is necessary and can be achieved by labelling of shoots in a 13CO2 atmosphere. Isolation of the headspace from the atmosphere has to be achieved, for example by an airtight Plexiglas chamber (Kuzyakov et al., 1999, 2001), and root and shoot zones have to be separated, for example by low melting paraffin overlaid by silicon paste. A sufficient amount of 13C is injected as 99 atom-% 13C-CO2 into the Plexiglas chamber, while tracking the absolute CO2 concentration in the chamber. The amount of label needed can be estimated from the strength of the label, the daily assimilation rate of the investigated plant species, and the targeted bulk soil enrichment.

Labelling can take place for short (1–3 h, pulse labelling), repeated, or long time periods (continuous labelling) according to the research question. During the labelling, i.e. the closure of the hoods, the climatic conditions inside the chamber have to be controlled. Subsequently, the remaining unassimilated 13CO2 from the Plexiglas chamber is continuously pumped through 1 M NaOH solution as a trap for CO2 and its concentration in the solution is subsequently analysed. The isotope C ratio in shoots, roots, microorganisms, dissolved organic carbon (DOC), soil, and trap solution are identified by isotope ratio mass spectrometry. The total assimilated 13C is the percentage of 13C added to plants after subtracting the unassimilated 13C. The net assimilated 13C is calculated from the percentage of 13C recovery, i.e. the sum of the 13C in shoots, roots, soil, and in soil respiration. The difference in d13C before and after the experiment can be compared with the natural d13C signature of roots for an estimation of rhizodeposition and for analysing the partitioning between plants, soil, and microbes. However, plant discrimination against 13C has to be considered for an interpretation of the results.

Alternatively, the natural abundance technique uses the isotopic signature difference between C3 and C4 plants to estimate the amount of C release by roots to soil: C4 plants are planted on C3 soil or vice versa (Cheng, 1996; Rochette & Flanagan, 1998). The method is based on the different isotopic discrimination of 13CO2 by Rubisco (ribulose-biphosphate carboxylase) enzymes of C3 plants and PEP (phosphoenolpyruvate) carboxylase of C4 plants, which results in a d13C signature of c. 27 ‰ in C3 plants and of c. 14 ‰ in C4 plants (Tieszen & Boutton, 1989), and consequently also in significant differences in the respective soils. The method is dependent on significant changes of the d13C signature in soil and is therefore often applied over one or even several growing seasons for a strong signal and combined with fractionation procedures. Finally, it is also possible to couple natural abundance and 13C pulse labelling for specific research questions (Werth & Kuzyakov, 2006).

Measurement unit: hours to days; Measurement scale: ground unit of a plot or site; Equipment costs: €€-€€€; Running costs: €€-€€€; Installation effort: high; Maintenance effort: medium; Knowledge need: high; Measurement mode: manual

Where to start

Kuzyakov & Domanski (2000), Luster & Finlay (2006), Neumann & Römheld (2007), Oburger & Schmidt (2016), Oburger & Jones (2018) Vranova et al. (2013).

2.1.5.2 Special cases, emerging issues, and challenges

Trap solution medium. Root exudation is influenced by the concentration gradient between roots and soil solution. Consequently, the nature of the trap solution will influence the amount of root exudation and the concentration of specific compounds (Kuijken et al., 2015). Sampling of root exudates in water for short time periods may lead to a potential overestimation of exudation rates as a consequence of osmosis between root cells and the low ionic strength solution (Neumann & Römheld, 2007; Vranova et al., 2013), while sampling in water over a long time period (> 24 h) may lead to an underestimation of exudation rates due to low nutrient availability in the solution (Jones & Darrah, 1993). It is assumed that exudation efflux generally increases and influx decreases with the strength of the solution (Vranova et al., 2013). Ideally, the trap solution should resemble the soil solution as closely as possible, for example by the use of a dilute nutrient solution (pH adjusted) that does not interfere with subsequent chemical analyses. Occasionally, ≥ 100 µM Ca2+ is added to the trap solution to ensure root membrane integrity (Vranova et al., 2013). Sterile conditions in the trap solution are sometimes maintained by the addition of a sterilising or protecting agent (e.g. antimicrobial compounds, K2SO4), yet rhizotoxic effects on the plant and the efficiency of their force in soil are disputed. Some authors note a negligible effect of microbial degradation for sampling periods of less than 24 h (Jones & Darrah, 1993), while others find significant effects (Kraffczyk et al., 1984).

Incubation period. Time is a very critical factor when sampling root exudates in steady-state in situ conditions. The amount of exuded compounds will increase over time and higher concentrations facilitate the chemical analyses, but, at the same time, the number of microbes invading the sampling agent will also increase over time, which decreases the concentration of exudates. Ideally, the exposition time is just long enough to yield enough signal for later analyses (which is species- and site-specific), but short enough to avoid significant microbial consumption (see also review by Oburger & Jones, 2018). The ideal time length should be estimated from prior time series of root exudate collection in combination with the intended chemical analysis. In addition, the diurnal cycle of photosynthate production has to be considered when planning the time for root exudate collections.

Resorption. Potential exudate resorption of the exuded compounds by the same roots has to be considered. C loss to the rhizosphere is generally not a unidirectional flux: a major part of the lost exudate C can be actively retrieved depending on the plant photosynthetic metabolism (Jones & Darrah, 1993; Sacchi et al., 2000). C4 plants retrieve up to 10% of LMWO compounds; whereas C3 plants may retrieve up to 70% of the exuded LMWO compounds (see review by Vranova et al., 2013).

2.1.5.3 References

Theory, significance, and large datasets

Neumann & Römheld (2007), Smit et al. (2000).

More on methods and existing protocols

Bromand et al. (2001), Dessureault-Rompré et al. (2006), Kuzyakov (2001), Phillips et al. (2008), Puschenreiter et al. (2005), Wenzel et al. (2001).

All references

Bais, H. P., Weir, T. L., Perry, L. G., Gilroy, S., & Vivanco, J. M. (2006). The role of root exudates in rhizosphere interactions with plants and other organisms. Annual Review in Plant Biology, 57, 233-266.

Brackin, R., Näsholm, T., Robinson, N., Guillou, S., Vinall, K., Lakshmanan, P., … Inselsbacher, E. (2015). Nitrogen fluxes at the root‐soil interface show a mismatch of nitrogen fertilizer supply and sugarcane root uptake capacity. Scientific Reports, 5, 15727.

Brackin, R., Atkinson, B. S., Sturrock, G. J., & Rasmussen, A. (2017). Roots‐eye view: Using microdialysis and microCT to nondestructively map root nutrient depletion and accumulation zones. Plant Cell and Environment, 40, 3135-3142.

Bromand, S., Whalen, J. K., Janzen, H. H., Schjoerring, J. K., & Ellert, B. H. (2001). A pulse-labelling method to generate 13C-enriched plant materials. Plant and Soil, 235, 253.

Canarini, A., Kaiser, C., Merchant, A., Richter, A., & Wanek, W. (2019) Root exudation of primary metabolites: Mechanisms and their roles in plant Responses to environmental stimuli. Frontiers in Plant Science, 10, 157.

Cheng, W. (1996). Measurement of rhizosphere respiration and organic matter decomposition using natural 13C. Plant and Soil, 183, 263-268.

Dessureault-Rompré, J., Nowack, B., Schulin, R., & Luster, J. (2006). Modified micro suction cup/ rhizobox approach for the in situ detection of organic acids in rhizosphere soil solution. Plant and Soil, 286, 99.

Gargallo-Garriga, A., Preece, C., Sardans, J., Oravec, M., Urban, O., & Peñuelas, J. (2018). Root exudate metabolomes change under drought and show limited capacity for recovery. Scientific Reports, 8, 12696.

Ge, T., Liu, C., Yuan, H., Zhao, Z., Wu, X., Zhu, Z., … Wu, J. (2015). Tracking the photosynthesized carbon input into soil organic carbon pools in a rice soil fertilized with nitrogen. Plant and Soil 392, 17-25.

Grayston, S. J., Vaughan, D., & Jones, D. (1997). Rhizosphere carbon flow in trees, in comparison with annual plants: the importance of root exudation and its impact on microbial activity and nutrient availability. Applied Soil Ecology, 5, 29-56.

Inselsbacher, E., Öhlund, J., Jämtgard, S., Huss-Danell, K., & Näsholm, T. (2011). The potential of microdialysis to monitor organic and inorganic nitrogen compounds in soil. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 43, 1321-1332.

Jones, D. L., & Darrah, P. R. (1993). Re-sorption of organic compounds by roots of Zea mays L. and its consequences in the rhizosphere. Plant and Soil, 153, 47-59.

Jones, D. L., Hodge, A., & Kuzyakov, Y. (2004) Plant and mycorrhizal regulation of rhizodeposition. New Phytologist, 163, 459-480.

Jones, D. L., Nguyen, C., & Finlay, R. D. (2009). Carbon flow in the rhizosphere: carbon trading at the soil-root interface. Plant and Soil, 321, 5-33.

Kuijken, R. C. P., Snel, J. F. H., Heddes, M. M., Bouwmeester, H. J., & Marcelis, L. F. M. (2015). The importance of a sterile rhizosphere when phenotyping for root exudation. Plant and Soil, 387, 131-142.

Kuzyakov, Y. (2001). Tracer studies of carbon translocation by plants from the atmosphere into the soil (a review). Eurasian Soil Science, 34, 28-42.

Kuzyakov, Y., & Domanski, G. (2000). Carbon input by plants into the soil. Review. Journal of Plant Nutrition and Soil Science, 163, 421-431.

Kuzyakov, Y., Kretzschmar, A., & Stahr, K. (1999). Contribution of Lolium perenne rhizodeposition to carbon turnover of pasture soil. Plant and Soil, 213, 127-136.

Kuzyakov, Y, Friedel J. K., & Stahr, K. (2000). Review of mechanisms and quantification of priming effects. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 32, 1485-1498.

Kuzyakov, Y., Ehrensberger, H., & Stahr, K. (2001). Carbon partitioning and below-ground translocation by Lolium perenne. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 33, 61-74.

Liese, R., Lübbe, T., Albers, N. W., & Meier, I. C. (2018). The mycorrhizal type governs root exudation and N uptake of temperate tree species. Tree Physiology, 38, 83-95.

Luo, Y., Su, B., Currie, W. S., Dukes, J. S., Finzi, A., Hartwig, U., … Field, C. B. (2004). Progressive nitrogen limitation of ecosystem responses to rising atmospheric carbon dioxide. BioScience, 54, 731-739.

Luster, J., & Finlay, R. (2006). Handbook of Methods Used in Rhizosphere Research. Birmensdorf: WSL.

Marschner, H. (1995). Mineral Nutrition of Higher Plants. Elsevier.

Meier, I. C., Finzi, A. C., & Phillips, R. P., (2017). Root exudates increase N availability by stimulating microbial turnover of fast-cycling N pools. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 106, 119-128.

Miró, M., & Frenzel, W. (2004). Implantable flow-through capillary-type microdialyzers for continuous in situ monitoring of environmentally relevant parameters. Analytical Chemistry, 76, 5974.

Miró, M., & Frenzel, W. (2005). The potential of microdialysis as an automatic sample‐processing technique for environmental research. Trends in Analytical Chemistry, 24, 324–333.

Miró, M., Fitz, W. J., Swoboda, S., & Wenzel, W. W. (2010). In situ sampling of soil pore water: evaluation of linear-type microdialysis probes and suction cups at varied moisture contents. Environmental Chemistry, 7, 123-131.

Neumann, G., & Römheld, V. (2007). The release of root exudates as affected by the plant physiological status. In R. Pinton, Z. Varanini, & Z. Nannipieri (Eds.), The Rhizosphere: Biochemistry and Organic Substances at the Soil-Plant Interface. (2nd ed., pp. 23-72). Boca Raton: CRC Press.

Oburger, E., & Schmidt, H. (2016). New methods to unravel rhizosphere processes. Trends in Plant Science, 21, 243-255.

Oburger, E., & Jones D. L. (2018). Sampling root exudates – Mission impossible? Rhizosphere 6, 116-133.

Phillips, R. P., Erlitz, Y., Bier, R., & Bernhardt, E. S. (2008). New approach for capturing soluble root exudates in forest soils. Functional Ecology, 22, 990-999.

Phillips, R. P., Finzi, A. C., & Bernhardt, E. S. (2011). Enhanced root exudation induces microbial feedbacks to N cycling in a pine forest under long-term CO2 fumigation. Ecology Letters, 14, 1887-1894.

Phillips, R. P., Meier, I. C., Bernhardt, E. S., Grandy, A. S., Wickings, K., & Finzi, A. C. (2012). Roots and fungi accelerate carbon and nitrogen cycling in a forest exposed to elevated CO2. Ecology Letters, 15, 1042-1049.

Puschenreiter, M., Wenzel, W. W., Wieshammer, G., Fitz, W. J., Wieczorek, S., Kanitsar, K., & Köllensperger, G. (2005). Novel micro-suction-cup design for sampling soil solution at defined distances from roots. Journal of Plant Nutrition and Soil Science, 168, 386-391.

Rochette, P., & Flanagan, L. B. (1998). Quantifying rhizosphere respiration in a corn crop under field conditions. Soil Science Society of America Journal, 61, 466-474.

Sacchi, G. A., Abruzzese, A., Lucchini, G., Fiorani, F., & Cocucci, S. (2000). Efflux and active re-absorption of glucose in roots of cotton plants grown under saline conditions. Plant and Soil, 220, 1-11.

Shaw, R., Williams, A. P., & Jones, D. L. (2014). Assessing soil nitrogen availability using microdialysis-derived diffusive flux measurements. Soil Science Society of America Journal, 78, 1797-1803.

Shi, S., Condron, L., Larsen, S., Richardson, A. E., Jones, E., Jiao, J., … Stewart, A., (2011). In situ sampling of low molecular weight organic anions from rhizosphere of radiata pine (Pinus radiata) grown in a rhizotron system. Environmental and Experimental Botany, 70, 131-142.

Smit, A. L., Bengough, A. G., Engels, C., van Noordwijk, M., Pellerin, S., & van de Geijn, S. C. (2000). Root Methods. A Handbook. Berlin: Springer.

Tieszen, L. L., & Boutton, T. W. (1989). Stable carbon isotopes in terrestrial ecosystem research. In P. W. Rundel, J. R. Ehleringer, & K. A. Nagy (Eds.), Stable Isotopes in Ecological Research (pp. 167-195). New York: Springer.

Vetterlein, D., & Jahn, R. (2004). Gradients in soil solution composition between bulk soil and rhizosphere ‑ in situ measurement with changing soil water content. Plant and Soil, 258, 307-317.

Vranova, V., Rejsek, K., Skene, K. R., Janous, D., & Formanek, P. (2013). Methods of collection of plant root exudates in relation to plant metabolism and purpose: A review. Journal of Plant Nutrition and Soil Science, 176, 175-199.

Wenzel, W. W., Wieshammer, G., Fitz, W. J., & Puschenreiter, M. (2001). Novel rhizobox design to assess rhizosphere characteristics at high special resolution. Plant and Soil, 237, 37-45.

Werth, M., & Kuzyakov, Y. (2006). Assimilate partitioning affects 13C fractionation of recently assimilated carbon in maize. Plant and Soil, 284, 319-333.

Whipps, J. M. (1990). Carbon economy. In J. M. Lynch (Ed.), The Rhizosphere (pp. 59-87). Chichester: Wiley and Sons.

Authors: Ostonen I1, Ven A2, Meier IC3

Reviewer: Preece, C4,5

Affiliations

1 Institute of Ecology and Earth Sciences, University of Tartu, Tartu, Estonia

2 Centre of Excellence PLECO (Plants and Ecosystems), Biology Department, University of Antwerp, Wilrijk, Belgium

3 Plant Ecology, Albrecht-von-Haller Institute for Plant Sciences, University of Goettingen, Goettingen, Germany

4 CSIC, Global Ecology Unit CREAF-CSIC-UAB, Bellaterra, Spain

5 CREAF, Cerdanyola del Vallès, Spain

Pingback:Belowground plant biomass – ClimEx Handbook