Authors: Djukic, I1

Reviewers: Almagro, M2, Hansen K3, Lee H4, Christiansen CT5

Measurement unit: mass loss %; Measurement scale: plot or site; Equipment costs: €; Running costs: €; Installation effort: low; Maintenance effort: low; Knowledge need: low; Measurement mode: manual

Decomposition is the breakdown (biological and chemical processes) and leaching of soluble compounds (physical process) of plant litter such as foliar, woody, and root litter, as well as of soil organic matter (SOM), with subsequent mineralisation and humification of organic compounds. It is a major determinant of carbon and nutrient cycling in ecosystems and a key driver of soil formation and fluxes of elements, such as carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), and nitrous oxide (N2O) into the atmosphere. An estimated 60 Pg CO2 is emitted annually by the decomposition of litter and soil organic matter (Houghton, 2007). Hence, litter turnover is of significant importance for the global carbon dioxide balance and is a proxy for ecosystem function. Anticipated increases in atmospheric CO2 as well as nitrogen (N) deposition might affect the quality of foliar litter (Norby et al., 2001) and climate change may substantially affect litter decomposition rates. However, considerable uncertainty remains in the decomposition patterns of plant litter and thus in the estimates of carbon dioxide emissions from the litter pool as well as in the size of the residual soil organic matter (SOM) relevant for carbon (C) dynamics of ecosystems.

2.2.6.1 What and how to measure?

The most commonly used approach to determine litter decomposition in all ecosystems is the litterbag method (Bocock & Gilbert, 1957). This method allows for measuring litter mass loss over a certain period and thus estimates decomposition rates. Litterbags can be prepared using site-specific litter (using one plant species or representative plant community mixes of litter from different species) or standard substrate.

Litterbags with site-specific (local) litter

Studies that use site-specific litter are commonly used to determine local litter decomposition since the decomposer communities are often adapted to the site-specific litter. The approach requires the collection of newly shed and intact mature shed leaves, the drying and preparation of the sampled litter, preparation of litterbags, weighing of the samples, installation of the litterbags in the field, and retrieval of incubated litterbags at given times. In forest ecosystems, recently senesced litter (leaves/needles) is collected during autumn, or during the dry season in tropical ecosystems with litter trap nets (e.g. 0.25 m2 and 1 mm mesh size; for more information see the ICP Forests Manual-Part XIII, 2016). An alternative is to use spread-out tarpaulins, which collect foliar litter across a larger surface or to gently shake shrub branches until leaves are shed directly into a bag. In grassland ecosystems, standing litter should be collected before winter by direct cutting from the plants. Loose plant material should be avoided, because it can be unclear if the litter is from this or a previous year. The newly collected foliage litter should be dried prior to incubation at 50 °C until constant weight. After incubation, the litter should be dried at the same temperature for 24 to 48 h in a ventilated oven.

Litterbags can be constructed from netting with different mesh sizes allowing size-selective exclusion of consumers: mesh size < 1 mm includes only microorganisms; mesh size > 1–2 mm includes meso-and micro-fauna; mesh size > 2 mm includes macro-, meso-, and micro-fauna; Bradford et al., 2002; Karberg et al., 2008). Polyester or high-density polyethylene nets for light-intensive sites are used for making bags. The litterbag size should be appropriate to the litter-size and is commonly 10 x 10 or 20 x 20 cm. Litterbags generally contain between 1–3 g of intact (not ground) material. The weight of the initial litter content with the litterbag should be recorded as precisely as possible (preferably to the 3rd or 4th decimal place). During transport to and from the field, it is important that the bags are not damaged and that no litter is lost. This may be taken care of by transporting the litterbag in paper envelopes. Label each bag with a unique identifier (e.g. metal plate with ascending numbers), or with a plastic tag giving the weighed litter mass. Metal plates will allow you to detect the bags with a metal detector at the end of the field-incubation period.

Litterbags with standard material

Common litterbag studies are most often conducted based on site-specific litter, making comparisons of different experiments and sites challenging. This is also partly due to the lack of common protocols and standard matrices. In the past, there have been several attempts to use a standardised material (e.g. cotton-strips (Latter & Howson, 1977), cellulose sheets (Rosswall & Veum, 1971)) for the estimation of litter decomposition. However, such materials are not representative of foliage litter decomposition.

Recently, the use of commercially available teabags as a pre-made “litterbag” with standardised litter material was introduced by Keuskamp et al. (2013). The Tea Bag method is a well-standardised, cost and time efficient method that provides proxy data on decomposition rates and litter stabilisation. Two types of tea material are used: i) green tea which is relatively labile and thus characterised by a higher decomposition rate and ii) rooibos tea which contains more structurally complex compounds and is characterised by a relatively low decomposition rate. It is crucial that the same tea content is used, therefore always check the EAN number when purchasing tea (green tea – Lipton Indonesian tea Sencha tradition: EAN 87 22700 05552 5 and rooibos tea: Lipton herbal infusion rooibos: EAN 87 22700 18843 8.

This common metric provides a reliable tool for inter-site and even global comparisons both in experimental and observation contexts (Borer et al.,2014; Verheyen et al., 2016). Decomposition of teabag material should be viewed as a proxy for decay rates. As such, the teabag method does not give a quantitative measure of local C losses and decomposition rates, since the tea is not equivalent to the site-specific litter, but it can be related to local rates (e.g. by simultaneous incubation of site-specific litter) and modelling.

Protocols for weighing samples and selecting plot sizes are the same as for standard litter.

Where to start

Berg (2000, 2014), Keuskamp et al. (2013)

Installation and field operation and interpretation

The start of incubation should be co-ordinated across the sites. The incubation length, however, depends on the research question. While the early decomposition stages (ca. 0–40% mass loss) are characterised by the mineralisation of preferential labile C sources and by leaching, the later stages (ca. 40–100% mass loss) are determined by mineralisation of recalcitrant C. Moreover, driving factors of different decomposition stages vary or change their directional effect (Berg, 2014). Since most climate simulation models need the temporal dynamics of litter C and nutrients, it is desirable to focus on medium- to long-term litter decomposition until the limit values (stage where litter mass is either stabilised or decomposes extremely slowly; Berg, 2000) are captured (i.e. incubation length > 1 year or more) and to include several sequential samplings.

Select homogenous replicate areas with uniform vegetation type, topography, and soil type, since any deviation in those parameters will influence the decomposition rates. Generally, we recommend that there should be at least three replicate areas per site or treatment with at least five replicate litterbags per replicate area and sampling point. The optimal plot size depends on the experimental set-up and ecosystem type. Usually, the plot size must be larger for forest ecosystems (e.g. 25 x 25 m) than for grassland ecosystems (e.g. 3 x 3 m). However, in experimental plots the size will be determined by the experimental set-up.

Litterbags can be incubated on the surface or buried into the upper soil layer (0–5 cm; Knacker et al., 2003). The choice of exposure can influence the litter decomposition, and for long-term decomposition trials with between-site comparisons, burial into the soil is preferred. The incubation layer should be marked. Samples should preferably be installed in straight lines in order to capture the same topography. Further, we advise installing the bags in the order of the planned sequential retrieval, to allow easy identification in case the labels get lost. Once the bags have been installed, the bags should be marked with a stick (place all sticks on the same side of the respective bags) and the lay-out should be sketched to aid the detection of the bags at the time of retrieval. Also record the date of the installation.

The retrieval date should be planned in relation to the date of installation. Make notes if the bags are damaged or already dug out as this is of relevance for data processing. Each litterbag should be placed in a separate plastic bag and relabelled if the initial labelling is unreadable. The litterbags should be processed as soon as possible. If they cannot be processed immediately, then the samples should be stored at -18 °C to prevent further decomposition. Remove all soil and root debris from the surface of the bags. Dry the bags at 50 °C until constant weight. Note the weight of remaining litter (without bag). Store the collected litter in paper bags (label them) for further analyses.

If the collected litter material is visibly contaminated with soil or the remaining weight is higher than the initial weight, then the ash content (i.e. the mineral residue after removal of organic matter by ignition) of the initial litter as well as after incubation should be determined by heating in a muffle oven at 500 °C for 16 h, to correct for the mineral part (Harmon et al., 1999; Soil Survey Staff, 2004). The ash weight can then be subtracted from the total dry weight in order to obtain the real end mass of the litter after incubation. Alternatevily, remainig carbon should be alanlysed. If roots and/or decomposers have entered the bag, all visible roots and/or decomposers should be removed manually.

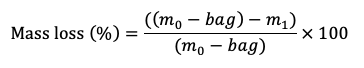

Litter mass loss is calculated as the difference between the initial dry mass and the final dry mass after the field incubation.

where:

m0 = weight of the initial litter with bag (g)

bag = weight of the empty litterbag (g)

m1 = weight of the litter at a given sampling point (g)

To interpret the mass loss, further parameters are needed. The minimum requirement would be to link the obtained mass loss to site climatic parameters (mean annual temperature, mean annual precipitation, annual mean temperature amplitude) and basic soil parameters (pH in CaCl2, organic carbon, total N, P, K, Ca, Mg, Mn). To understand the nutrient release processes during decomposition of soil and litter, nutrient data in the litter before and after incubation (N, P, S, K, Ca, Mg, Mn, lignin) will be needed. For this, a multi-element extraction should be applied (Pleysier & Juo, 1980). In optimal cases, it would be advisable to take continuous measurements of litter temperature and moisture using sensors within litterbags to record local climatic conditions (Wang et al., 2015). When litterbags are made with isotopic labelled litter, measurement of 13C and 15N through the decomposition process will provide valuable insights into the involvement of microorganisms in the decomposition process (e.g. Djukic et al., 2013). Also, combining litterbags with experimental studies (e.g. rain maniputlation, soil fertilisation) or elevation gradients (e.g. tree-line shifts) will allow a better understanding of other global-change drivers relevant for decomposition processes. Similarly, involving litterbag studies in monitoring studies such as soil carbon stocks inventories (e.g. FAO Soil Carbon Partnership, national soil inventories) or belowground diversity observations (e.g. GEO BON) will provide a powerful link between the potential drivers and functions, which is of particular interest for interpreting the effects of climate and biodiversity change.

A wide range of carbon and ecosystem models already use a decay process (typically with different representations of the decay process based on molecular structure and chemical composition of the litter that decomposes at unique rates, etc.) to simulate C dynamics. To run a simple dynamic C model (e.g. Soil Carbon Model – Yasso, 2017) information on chemical AWEN fractions – i) compounds hydrolysable in acid, ii) compounds soluble in water, iii) compounds soluble in a non-polar solvent (ethanol or dichloromethane), and iv) compounds neither soluble nor hydrolysable – of the litter type should be determined if they are not listed on the Yasso website (Yasso, 2017).

Where to start

Harmon et al. (1999), Knacker et al. (2003), Pleysier & Juo (1980), Soil Survey Staff (2004), Wang et al. (2015), Yasso (2017)

2.2.6.2 Special cases, emerging issues, and challenges

In ecosystems where litter decomposition is strongly affected by the activity of macro- and meso-fauna (e.g. tropical ecosystems), incubation of litterbags with different mesh sizes is recommended in order to obtain the best information on litter decomposition dynamics (Powers et al., 2009).

Annual water-level fluctuations affect litter decomposition in wetlands: therefore frequent sampling that covers all variations during litter decomposition over a long-term is essential for the fundamental understanding of decomposition processes in these environments.

In semi-arid ecosystems, photodegradation is one of the controlling factors of aboveground litter decomposition. If litterbags are incubated on the surface, high-density polyethylene nets should be used for the litterbag in order to inhibit bag degradation. Moreover, regardless of the material type used to construct the litterbags, the % of UV transmittance should be measured and reported. Soil erosion by water or wind can also affect litter decomposition in arid and semi-arid ecosystems, as well as interact with photodegradation (Throop & Archer, 2008). So, these novel drivers (i.e. photodegradation, non-rainfall water sources, fragmentation by soil transport) of litter decomposition in arid and semi-arid ecosystems have to be considered when designing experiments in these regions.

When using teabags to investigate litter decomposition, one should bear in mind that the tea material (especially green tea) is prone to leaching, which in turn has to be considered when incubating bags and analysing data (Djukic et al., 2018).

2.2.6.3 References

Theory, significance, and large datasets

Berg & McClaugherty (2003), Powers et al. (2009), Prescott (2010), Tuomi et al. (2009), Vitousek et al. (1994)

More on methods and existing protocols

There have been many litterbag studies, providing a good source for different methods and protocols:

- Long-Term Intersite Decomposition Experiment (LIDET)

- Global Litter Invertebrate Decomposition Experiment (GLIDE)

- The Detrital Input and Removal Experiment (DIRT)

- TeaComposition – A Global Litter Decomposition Study

All references

Berg, B. (2000). Litter decomposition and organic matter turnover in northern forest soils. Forest Ecology and Management, 133(1-2), 13-22.

Berg, B. (2014). Decomposition patterns for foliar litter – a theory for influencing factors. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 78, 222-232.

Berg, B., & McClaugherty, C. (2003). Plant Litter: Decomposition, Humus Formation, Carbon Sequestration. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

Bocock, K. L., & Gilbert, O. J. W. (1957). The disappearance of leaf litter under different woodland conditions. Plant and Soil, 9(2), 179-185.

Borer, E. T., Harpole, W. S., Adler, P. B., Lind, E. M., Orrock, J. L., Seabloom, E. W., & Smith, M. D. (2014). Finding generality in ecology: a model for globally distributed experiments. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 5(1), 65-73.

Bradford, M. A., Tordoff, G. M., Eggers, T., Jones, T. H., & Newington, J. E. (2002). Microbiota, fauna, and mesh size interactions in litter decomposition. Oikos, 99(2), 317-323.

Djukic, I., Zehetner, F., Watzinger, A., Horacek, M., & Gerzabek, M. H. (2013). In situ carbon turnover dynamics and the role of soil microorganisms therein: a climate warming study in an Alpine ecosystem. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 83(1), 112-124.

Djukic, I., Kepfer-Rojas, S., Schmidt, I.K., Larsen, K.S., Beier, C., Berg, B., & Verheyen, K. (2018). Early stage litter decomposition across biomes. Science of the Total Environment, 628-629, 1369-1394.

Harmon, M. E., Nadelhoffer, K. J., & Blair, J. M. (1999). Measuring decomposition, nutrient turnover and stores in plant litter. In G. Robertson, et al. (Eds.), Standard Methods for Long-Term Ecological Research (pp. 202–240). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Houghton, R. A. (2007). Balancing the global carbon budget. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Science, 35, 313-347.

ICP Forests Manual (2016). http://icp-forests.net/page/icp-forests-manual (accessed 23 May 2018).

Karberg, N. J., Scott, N. A., & Giardina, C. P. (2008). Methods for estimating litter decomposition. In C. M. Hoover (Ed.), Field Measurements for Forest Carbon Monitoring (pp. 103-111). Dordrecht: Springer.

Keuskamp, J. A., Dingemans, B. J., Lehtinen, T., Sarneel, J. M., & Hefting, M. M. (2013). Tea Bag Index: a novel approach to collect uniform decomposition data across ecosystems. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 4(11), 1070-1075.

Knacker, T., Förster, B., Römbke, J., & Frampton, G. K. (2003). Assessing the effects of plant protection products on organic matter breakdown in arable fields — litter decomposition test systems. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 35(10), 1269-1287.

Latter, P. M., & Howson, G. (1977). Use of cotton strips to indicate cellulose decomposition in the field. Pedobiologia 17, 145-155.

Norby, R. J., Cotrufo, M. F., Ineson, P., O’Neill, E. G., & Canadell, J. G. (2001). Elevated CO2, litter chemistry, and decomposition: a synthesis. Oecologia, 127(2), 153-165.

Pleysier, J. L., & Juo, A. S. R. (1980). A single-extraction method using silver-thiourea for measuring exchangeable cations and effective CEC in soils with variable charges. Soil Science, 129(4), 205-211.

Powers, J. S., Montgomery, R. A., Adair, E. C., Brearley, F. Q., DeWalt, S. J., Castanho, C. T., … González‐Iturbe, J. A. (2009). Decomposition in tropical forests: a pan‐tropical study of the effects of litter type, litter placement and mesofaunal exclusion across a precipitation gradient. Journal of Ecology, 97(4), 801-811.

Prescott, C. E. (2010). Litter decomposition: what controls it and how can we alter it to sequester more carbon in forest soils? Biogeochemistry, 101(1-3), 133-149.

Rosswall, T., & Veum, A. K. (1971). Notes on the use of paper pulp for cellulose decomposition determinations. IBP Swedish Tundra Biome Project Technical Report, 6, 7-8.

Soil Survey Staff (2004). Soil survey laboratory methods manual. Soil Survey Investigations Report 42. Washington, DC: USDA – NRCS.

Throop, H. L., & Archer, S. R. (2008). Shrub (Prosopis velutina) encroachment in a semi-desert grassland: spatial–temporal changes in soil organic carbon and nitrogen pools. Global Change Biology, 14(10), 2420-2431.

Tuomi, M., Thum, T., Järvinen, H., Fronzek, S., Berg, B., Harmon, M., … Liski, J. (2009). Leaf litter decomposition – Estimates of global variability based on Yasso07 model. Ecological Modelling, 220(23), 3362-3371.

Verheyen, K., De Frenne, P., Baeten, L., Waller, D. M., Hédl, R., Perring, M. P., … & De Lombaerde, E. (2016). Combining biodiversity resurveys across regions to advance global change research. BioScience, 67(1), 73-83.

Vitousek, P. M., Turner, D. R., Parton, W. J., & Sanford, R. L. (1994). Litter decomposition on the Mauna Loa environmental matrix, Hawai’i: patterns, mechanisms, and models. Ecology, 75(2), 418-429.

Wang, L., Throop, H. L., & Gill, T. (2015). A novel method to continuously monitor litter moisture – A microcosm-based experiment. Journal of Arid Environments, 115, 10-13.

Yasso Soil Carbon Model (2017). http://www.syke.fi/projects/yasso (accessed 23 May 2018).

Authors: Djukic, I1

Reviewers: Almagro, M2, Hansen K3, Lee H4, Christiansen CT5

Affiliations

1 Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape ResearchWSL, Birmensdorf, Switzerland.

2 BC3-Basque Centre for Climate Change, University of the Basque Country, Leioa, Spain

3 Swedish Environmental Protection Agency, Stockholm, Sweden.

4 NORCE Norwegian Research Centre and Bjerknes Centre for Climate Research, Bergen, Norway