Authors: Robinson DA1 and Marshall M.1

Reviewers: Jones SB2, Reinsch S1

Measurement unit: volumetric water content (m3 m-3) v. soil matric potential (kPa); Measurement scale: plot; Equipment costs: €€€; Running costs: €; Installation effort: medium; Maintenance effort: medium; Knowledge need: moderate; Measurement mode: manual

Drought and flooding, as well as changes to land use can cause changes to soil structure, which in turn will alter the hydraulic response of the soil and the soil’s ability to retain water (Robinson et al., 2019). Soil hydraulic properties primarily control the partitioning of water between what infiltrates into the soil and what runs off. The soil water retention curve or, water release curve (WRC), defines the relationship between the soil volumetric moisture content (Θ) and the pressure head (h). Hydraulic conductivity is a function of the soil saturated hydraulic conductivity (Ks), and can also be defined in terms of h or Θ (Ramos et al., 2006; Sakai et al., 2015). The relationships Θ(h), K(h), and K(Θ) define hydraulic properties of soil within the context of the Richards equation, which describes unsaturated water movement through soil (Rashid et al., 2015). These relationships are highly non-linear and vary as a function of soil texture (van Genuchten, 1980), but are also influenced by biotic and abiotic factors (Marshall et al., 2009). Accurate estimates of soil hydraulic properties are critical for simulating a range of soil hydrological processes, including water infiltration, surface runoff, evaporation, transpiration, profile soil moisture content, and solute transport (Ritchie et al., 1972; Gupta & Larson, 1979; Novak et al., 2000; Siyal et al., 2013; Sakai et al., 2015). These properties also have a direct impact on gaseous movement and heat transfer with subsequent impacts on many biogeochemical properties and processes. Soil hydraulic properties are used to address problems across a range of disciplines including ecology, environmental sciences, biogeochemistry, and agriculture (Durner & Flühler, 2005) and are a requirement to evaluate water and energy balances between the land surface and atmosphere within global circulation models (Mohanty et al., 2002). Robinson et al. (2016) measured climate change-induced shifts in soil hydraulic properties of an Atlantic heath resulting from drought-induced changes to soil structure; this led to a change in soil moisture dynamics and a change in the ability to retain soil moisture.

3.3.1 What and how to measure?

Soil water retention measurement

Numerous methods exist for quantifying soil hydraulic properties either directly through laboratory or field measurements (Šimůnek & van Genuchten 1996; Shao & Horton, 1998; Dane & Topp, 2002; Fujimaki & Inoue, 2003) or indirectly through the use of pedotransfer functions (PTFs) or inverse solutions of the Richards flow equation (Neuman, 1973). PTFs are equations used for the indirect estimation of a soil from more easily measured properties such as bulk density and texture (Parasuraman et al., 2007; Vereecken et al., 2010; also see protocol 1.3 Soil types and physical characteristics). Much research has focused on developing a function that can describe the WRC across all soil types but as yet no single function can be described as generic. Inverse solution methods have been used to estimate WRC by minimising the sum of squared deviations between observed and predicted transient flow data (Rashid et al., 2015; Hopmans et al., 2002). However, this requires data describing soil moisture dynamics that are both representative and accurate.

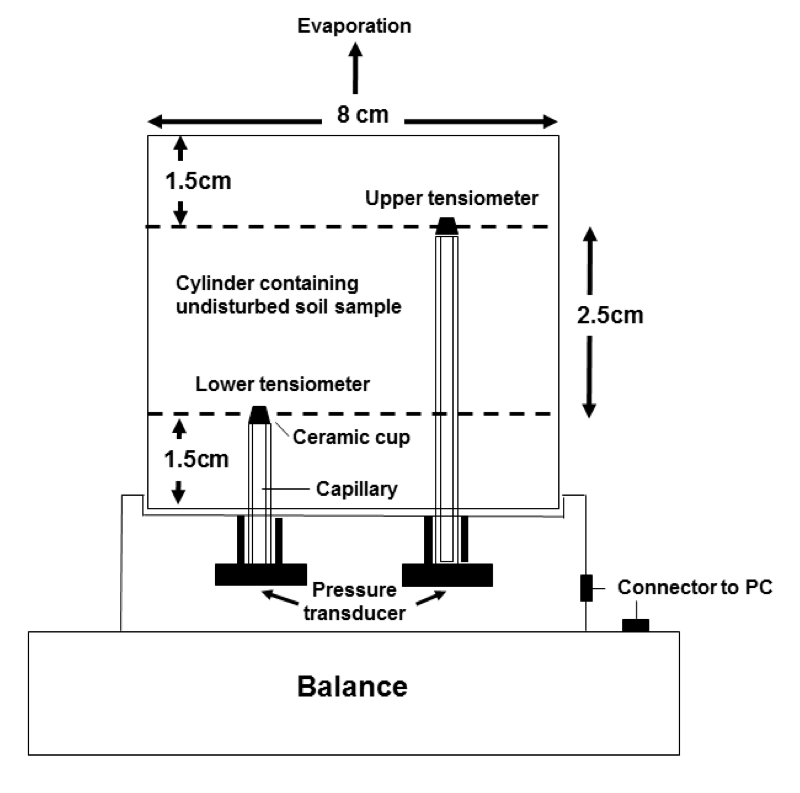

To determine the impact of climate change on soil hydraulic properties we need to measure parameters that are relevant, indicative of change, and sensitive to the treatments applied. The evaporation method first considered in the 1960s, and simplified by Schindler & Müller (2006), is a commonly used laboratory procedure allowing accurate characterisation of soil hydraulic properties at the wet en

d of the WRC. The method works by calculating the WRC and unsaturated hydraulic conductivity simultaneously from measuring the changes in weight and tension of a saturated soil sample dried by evaporation. Tensiometer measurement limitations mean that the method only works between 0 to ~-80 kPa (Schindler et al., 2010).

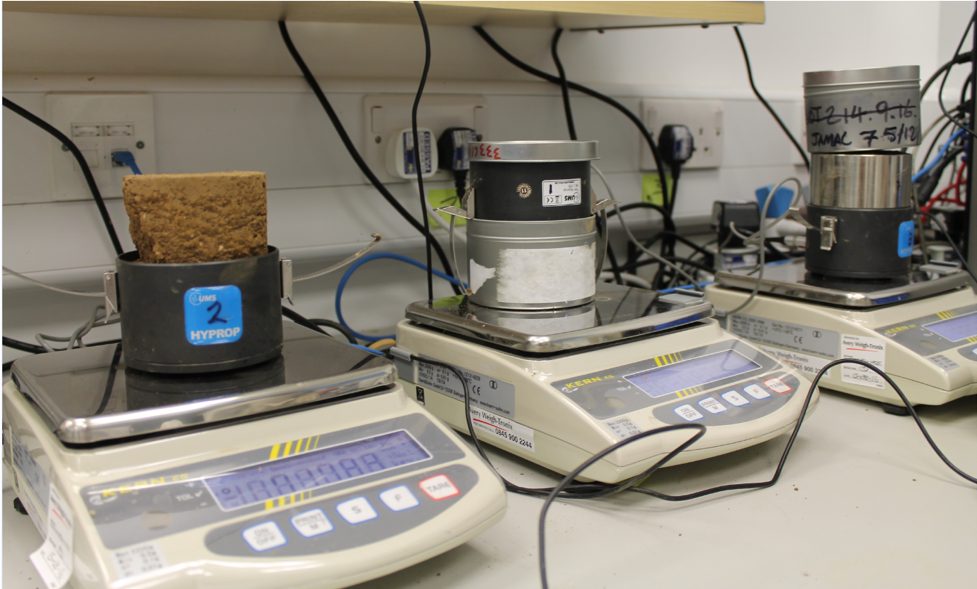

At higher suctions, the dry end of the WRC can be evaluated by determining the relative humidity (Rh) of soil air considered to be in equilibrium with the soil water phase using the chilled mirror method (Jensen et al., 2015). Samples are equilibrated within a sealed chamber containing a controlled temperature mirror with the means of detecting condensation. Decagon Devices Inc. (Pullman) offer two commercially available apparatuses that determine soil moisture relationships across both the wet and dry ends of the WRC. The HYPROP® system performs the evaporation method using two tensiometers and a weighing balance (Figure 3.3.1a and b) to provide estimates of Θ(h) and K(h) (Shindler et al., 2010). The WP4 (models T and now C) Water Potentiameter is a hygrometer that performs the chilled mirror dew-point method to measure soil moisture potential at the dry end of the WRC. The gravimetric moisture content, Θg, of the WP4 samples are then determined in the standard method and converted to volumetric moisture content, Θv, to determine Θ(h) at the dry end.

Where to start

If using the evaporation method (Schindler & Müller, 2006; Schindler et al., 2010) read the instructions book. More detail can be found in the following articles: Dane & Topp (2002), Durner & Flühler (2005).

3.3.2 Special cases, emerging issues, and challenges

Retention measurements are challenging to do correctly. If using the evaporation method some practice will help. Soil cores can be taken from any soil depth of interest considering that the HYPROP rings are 5 cm in height. If soil cores are taken from deeper down in the profile, a soil pit needs digging with enough space to allow the space for the equipment and to lever the soil core out. Ensure any cores taken in the field are completely filled with soil and no gaps are left by stones etc. Soil protruding the ring edge can easily be sliced off using an ordinary bread knife. Cores can be kept moist by wrapping them in cling film. In the lab always saturate from the bottom up, this is ensured by clearly marking the top and the bottom of the core in the field. Try to keep the temperature relatively constant by best storing the cores in a fridge (e.g. 4oC). No storage limit is known but cores need to be retained at field moisture without perturbation. If possible process cores quickly to avoid disturbances. Be careful using tensiometers – they are fragile and easily broken – do not over tighten or apply excess force (i.e. via syringe) to the pressure transducers, exceeding their capacity and breaking the fragile membrane.

3.3.3 References

Theory, significance, and large datasets

Cosby et al. (1984), Peters & Durner (2006), Robinson et al. (2016), Schaap & Leij (1998a, 1998b), Schaap et al. (2001), van Genuchten (1980)

Methods and protocols

Schindler & Müller (2006), Schindler et al. (2010)

All references

Cosby, B. J., Hornberger, G. M., Clapp, R. B., & Ginn, T. (1984). A statistical exploration of the relationships of soil moisture characteristics to the physical properties of soils. Water Resources Research, 20(6), 682-690.

Dane, J. H., & Topp, C. G. (Eds.) (2002). Methods of Soil Analysis, Part 4—Physical Methods. Madison: Soil Science Society of America.

Durner, W., & Flühler, H. (2005). Soil hydraulic properties. In M. G. Anderson, & J. J. McDonnell (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Hydrological Sciences. Wiley.

Fujimaki, H., & Inoue, M. (2003). A transient evaporation method for determining soil hydraulic properties at low pressure. Vadose Zone Journal, 2(3), 400-408.

Gupta, S., & Larson, W. E. (1979). Estimating soil water retention characteristics from particle size distribution, organic matter percent, and bulk density. Water Resources Research, 15(6), 1633-1635.

Hopmans, J. W., Šimůnek, J., Romano, N., & Durner, W. (2002). Inverse methods. In J. H. Dane, & C. G. Topp (Eds.), Methods of Soil Analysis, Part 4—Physical Methods (pp. 963-1008). Madison: Soil Science Society of America.

Jensen, D. K., Tuller, M., de Jonge, L. W., Arthur, E., & Moldrup, P. (2015). A new two-stage approach to predicting the soil water characteristic from saturation to oven-dryness. Journal of Hydrology, 521, 498-507.

Marshall, M. R., Francis, O. J., Frogbrook, Z. L., Jackson, B. M., McIntyre, N., Reynolds, B., … Chell, J. (2009). The impact of upland land management on flooding: results from an improved pasture hillslope. Hydrological Processes, 23(3), 464-475.

Mohanty, B. P., Shouse, P. J., Miller, D. A., & van Genuchten, M. T. (2002). Soil property database: Southern Great Plains 1997 hydrology experiment. Water Resources Research, 38(5), WR000076.

Neuman, S. P. (1973). Calibration of distributed parameter groundwater flow models viewed as a multiple‐objective decision process under uncertainty. Water Resources Research, 9(4), 1006-1021.

Novak, V., Šimåunek, J., & van Genuchten, M. T. (2000). Infiltration of water into soil with cracks. Journal of Irrigation and Drainage Engineering, 126(1), 41-47.

Parasuraman, K., Elshorbagy, A., & Si, B. C. (2007). Estimating saturated hydraulic conductivity using genetic programming. Soil Science Society of America Journal, 71(6), 1676-1684.

Peters, A., & Durner, W. (2006). Improved estimation of soil water retention characteristics from hydrostatic column experiments. Water Resources Research, 42(11), WR004952.

Ramos, T. B., Goncalves, M. C., Martins, J. C., van Genuchten, M. T., & Pires, F. P. (2006). Estimation of soil hydraulic properties from numerical inversion of tension disk infiltrometer data. Vadose Zone Journal, 5(2), 684-696.

Rashid, N. S. A., Askari, M., Tanaka, T., Simunek, J., & van Genuchten, M. T. (2015). Inverse estimation of soil hydraulic properties under oil palm trees. Geoderma, 241, 306-312.

Ritchie, J. T. (1972). Model for predicting evaporation from a row crop with incomplete cover. Water Resources Research, 8(5), 1204-1213.

Robinson, D. A., Jones, S. B., Lebron, I., Reinsch, S., Domínguez, M. T., Smith, A. R., … Emmett, B. A. (2016). Experimental evidence for drought induced alternative stable states of soil moisture. Scientific Reports, 6, 20018.

Robinson, D. A., Hopmans, J. W., Filipovic, V., van der Ploeg, M., Lebron, I., Jones, S. B., … Tuller, M. (2019). Global environmental changes impact soil hydraulic functions through biophysical feedbacks. Global Change Biology. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14626

Sakai, M., van Genuchten, M. T., Alazba, A. A., Setiawan, B. I., & Minasny, B. (2015). A complete soil hydraulic model accounting for capillary and adsorptive water retention, capillary and film conductivity, and hysteresis. Water Resources Research, 51(11), 8757-8772.

Schaap, M. G., & Leij, F. J. (1998a). Using neural networks to predict soil water retention and soil hydraulic conductivity. Soil and Tillage Research, 47(1), 37-42.

Schaap, M. G., & Leij, F. J. (1998b). Database-related accuracy and uncertainty of pedotransfer functions. Soil Science, 163(10), 765-779.

Schaap, M. G., Leij, F. J., & van Genuchten, M. T. (2001). ROSETTA: a computer program for estimating soil hydraulic parameters with hierarchical pedotransfer functions. Journal of Hydrology, 251(3), 163-176.

Schindler, U., & Müller, L. (2006). Simplifying the evaporation method for quantifying soil hydraulic properties. Journal of Plant Nutrition and Soil Science, 169(5), 623-629.

Schindler, U., Durner, W., von Unold, G., Mueller, L., & Wieland, R. (2010). The evaporation method: extending the measurement range of soil hydraulic properties using the air‐entry pressure of the ceramic cup. Journal of Plant Nutrition and Soil Science, 173(4), 563-572.

Shao, M., & Horton, R. (1998). Integral method for estimating soil hydraulic properties. Soil Science Society of America Journal, 62(3), 585-592.

Šimůnek, J., & van Genuchten, M. T. (1996). Estimating unsaturated soil hydraulic properties from tension disc infiltrometer data by numerical inversion. Water Resources Research, 32(9), 2683-2696.

Siyal, A. A., van Genuchten, M. T., & Skaggs, T. H. (2013). Solute transport in a loamy soil under subsurface porous clay pipe irrigation. Agricultural Water Management, 121, 73-80.

Van Genuchten, M. T. (1980). A closed-form equation for predicting the hydraulic conductivity of unsaturated soils. Soil Science Society of America Journal, 44(5), 892-898.

Vereecken, H., Weynants, M., Javaux, M., Pachepsky, Y., Schaap, M. G., & van Genuchten, M. T. (2010). Using pedotransfer functions to estimate the van Genuchten–Mualem soil hydraulic properties: a review. Vadose Zone Journal, 9(4), 795-820.

Authors: Robinson DA1 and Marshall M.1

Reviewers: Jones SB2, Reinsch S1

Affiliations

1 Centre for Ecology & Hydrology, Environment Centre Wales, Bangor, UK

2 Dep. of Plants, Soils and Climate, Utah State Univ., Logan, USA