Authors: Lebron I1 and Robinson DA1

Reviewer: Reinsch S1

Measurement unit: s (seconds); Measurement scale: plot; Equipment costs: €; Running costs: -; Installation effort: -; Maintenance effort: -; Knowledge need: low; Measurement mode: manual

Soil water repellency (SWR) is the inability of water to wet or infiltrate a soil. SWR affects water infiltration, soil water retention, and soil water content and thus plant and microbial available water (Doerr et al., 2000; Hallett, 2008; Dekker et al., 2009). Multiple factors are thought to contribute to the development of SWR and include litter breakdown products, such as waxes, root exudates, fungi, and bacteria, and litter structures such as a rugose surface. SWR is most evident when the soil dries below a critical water content, leading to movement and reorganisation of organic solutes at the soil/water interface, often creating a water repellent coating (Wallis & Horne, 1992; Ritsema & Dekker, 1996). SWR has been used in studies characterising land-use change (Lebron et al., 2012), effect of fire (DeBano, 2000b), and in transect studies looking at the patterns and finger flow caused by SWR (Robinson et al., 2010). The distribution of SWR in soils has high spatial variability (Lozano et al., 2013) with isolated patches of SWR and soil water content. Such variability can be critical because spatial isolation may be the key in structuring soil microbial communities (Treves et al., 2003).

Although most noticeable in dry soils, the impacts of SWR are persistent in wet soils, for example reduced infiltration rates and water-holding capacity can occur due to air entrapment (van Dam et al., 1990). SWR has been reported under all climatic and geographic conditions as well as in all soil types: SWR is regularly observed in most land-use and management types, and is often independent of organic matter content and soil texture (Doerr et al., 2006; Dekker et al., 2009). Climate change may increase the prevalence of SWR through increased frequency of extreme events such as drought and storms, or the increased occurrence of fire (Goebel et al., 2011). Given that SWR can induce a shift of soil moisture to an alternative stable state, altering infiltration processes from piston flow and uniform wetting to bypass flow and heterogeneous wetting, it can have a substantial impact on microbial activity, biogeochemical cycling, and gas fluxes.

3.6.1 What and how to measure?

Soil water repellency measurement

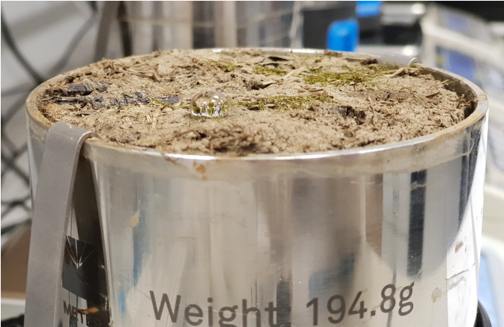

Soil water content and temperature are the main factors to control when measuring SWR. Although SWR can be measured in the field, the best, most reproducible results are measured in the laboratory under controlled conditions on air-dry samples. Ideally, an undisturbed soil core from the top 2 cm is collected (this may be a core extracted for bulk density or other measurements). SWR is then measured under a laboratory temperature of 20–25 oC using the water drop penetration time (WDPT, see Figure 3.6.1) test (Van’t Woudt, 1959), for example. In the WDPT test, water drops are applied to the soil and the length of time it takes for the water drops to penetrate the soil is measured. A longer duration indicates stronger water repellency. The WDPT is best characterised as measuring the persistence or stability of soil water repellency (Letey et al., 2000). The WDPT test groups soils into six classes according to the time taken for water penetration (see below).

The WDPT test separates soils which are classified as being water repellent from those which are not. Since water penetrates the soil if the contact angle (θ) is less than 90 °, WDPT is a measure of the time required for θ to change from its original value, which was greater than 90 °, to a value approaching 90 °. Therefore, it is a measurement of the stability of the repellency, or persistence. In repellent soils, it takes a considerable time for the drop to penetrate the soil. For this reason, work previously published may have a maximum time of observation, which effectively truncates the data and varies according to different authors. A minimum time of at least 6 h is preferred (see below). In order to reduce observation time the process can be filmed using a microcamera with a timer connected to a computer, which when replayed provides the exact time at which the drop disappears from the soil surface and can easily be reviewed.

|

|

|

Figure 3.6.1 Measurements of water drop penetration time: A drop of 100 µl deionised water on a vegetation-free soil surface of a dried soil core (left) and a close-up of the drop (right). Photo: Francis Parry (Centre for Ecology & Hydrology). |

|

Example method

- Take the undisturbed, air-dried soil core (top 2 cm) and remove the loose litter or green vegetation from the top of the soil.

- Place the soil-surface sample under a USB microcamera on a stand.

- Pipette at least 6 distinct 100 µl drops of deionised water on to the soil surface, avoiding any vegetation or root matter.

- When all drops have been absorbed into the soil surface ensure all files are saved.

- Record the time at which each drop disappeared from the surface of the soil.

- The median of the six drops constitutes the penetration time for that sample.

Water penetration time for the soil is estimated as the median rather than the average since the median eliminates the bias that one or two drops with very long penetration times can introduce. The use of digital recording for the collection of data eliminates the need to set a maximum time of observation that can effectively truncate the data, in this way we collect the real time for the water to infiltrate even for those soils which are highly water repellent and may take 5 or 6 hours.

Interpretation

Penetration times are used to classify the soil according to different repellency levels. Different authors use different definitions for the various water repellency classes, however most scientists agree that when penetration time is higher than 1 hour, the soil is severely water repellent, and below 5 seconds the soil is not water repellent. It is preferable to report the WDPT in seconds, but there are also WDPT repellency classes. Class 0: non-repellent (infiltration within 5 s); class 1: slightly water repellent (5–60 s); class 2: strongly water repellent (60–600 s); class 3: severely water repellent (600–3600 s); class 4: extremely water repellent (1–3 h); class 5: extremely water repellent (3–6 h); and class 6 (> 6 h) (Dekker et al., 2009).

Where to start

Doerr et al. (2000), Dekker et al. (2009), Letey et al. (2000)

3.6.2 Special cases, emerging issues, and challenges

While initially considered an issue in fire-prone Mediterranean climates, it is becoming clear that SWR is a much broader issue. Understanding the distribution, ecological significance, and mechanisms generating SWR remain a challenge.

Other methods of soil water repellency measurement

The molarity of an ethanol droplet (MED) test (also known as the percentage ethanol or critical surface tension test) is also used to measure SWR (Letey et al., 2000). In the MED test, drops with an increasing concentration of ethanol are applied to the soil in order to indirectly measure the apparent surface tension. This effectively determines how strongly the water is repelled, and this property is best reported as the strength or severity of SWR as distinct from the WDPT persistence (Letey et al., 2000).

3.6.3 References

Theory, significance, and large datasets

DeBano (2000a, 2000b), Doerr et al. (2000), Hallett (2008), Ritsema & Dekker (1994)

More on methods and existing protocols

Hallin et al. (2013)

All references

DeBano, L. F. (2000a). Water repellency in soils: a historical overview. Journal of Hydrology, 231, 4-32.

DeBano, L. F. (2000b). The role of fire and soil heating on water repellency in wildland environments: a review. Journal of Hydrology, 231, 195-206.

Dekker, L. W., Ritsema, C. J., Oostindie, K., Moore, D., & Wesseling, J. G. (2009). Methods for determining soil water repellency on field‐moist samples. Water Resources Research, 45(4), WR007070.

Doerr, S. H., Shakesby, R. A., & Walsh, R. (2000). Soil water repellency: its causes, characteristics and hydro-geomorphological significance. Earth-Science Reviews, 51(1), 33-65.

Doerr, S. H., Shakesby, R. A., Dekker, L. W., & Ritsema, C. J. (2006). Occurrence, prediction and hydrological effects of water repellency amongst major soil and land‐use types in a humid temperate climate. European Journal of Soil Science, 57(5), 741-754.

Goebel, M. O., Bachmann, J., Reichstein, M., Janssens, I. A., & Guggenberger, G. (2011). Soil water repellency and its implications for organic matter decomposition–is there a link to extreme climatic events? Global Change Biology, 17(8), 2640-2656.

Hallett, P. D. (2008). A brief overview of the causes, impacts and amelioration of soil water repellency – a review. Soil and Water Research, 3(1), 521-528.

Hallin, I., Douglas, P., Doerr, S. H., & Bryant, R. (2013). The role of drop volume and number on soil water repellency determination. Soil Science Society of America Journal, 77(5), 1732-1743.

Lebron, I., Robinson, D. A., Oatham, M., & Wuddivira, M. N. (2012). Observation of soil water repellency and pH soil change under tropical pine plantations compared with native tropical forest. Journal of Hydrology, 414-415, 194-200.

Letey, J., Carrillo, M. L. K., & Pang, X. P. (2000). Approaches to characterize the degree of water repellency. Journal of Hydrology, 231, 61-65.

Lozano, E., Jiménez-Pinilla, P., Mataix-Solera, J., Arcenegui, V., Bárcenas, G.M., González-Pérez, J.A., … Mataix-Beneyto, J. (2013). Biological and chemical factors controlling the patchy distribution of soil water repellency among plant species in a Mediterranean semiarid forest. Geoderma, 207, 212-220.

Ritsema, C. J., & Dekker, L. W. (1994). How water moves in a water repellent sandy soil: 2. Dynamics of fingered flow. Water Resources Research, 30(9), 2519-2531.

Ritsema, C. J., & Dekker, L. W. (1996) Water repellency and its role in forming preferred flow paths in soils. Australian Journal of Soil Research, 34, 475-487.

Robinson, D. A., Lebron, I., Ryel, R. J., & Jones, S. B. (2010). Soil water repellency, a method of soil moisture sequestration in Pinyon – Juniper woodland. Soil Science Society of America Journal, 74, 624-634.

Treves, D. S., Xia, B., Zhou, J., & Tiedje, J. M. (2003). A two-species test of the hypothesis that spatial isolation influences microbial diversity in soils. Microbial Ecology, 45, 20-28.

Wallis, M. G. & Horne, D. J. (1992). Soil water repellency. Advances in Soil Science, 20, 91-146.

Van Dam, J. C., Hendrickx, J. M. H., van Ommen, H. C., Bannink, M. H., van Genuchten, M. T., & Dekker, L. W. (1990). Water and solute movement in a coarse-textured water-repellent field soil. Journal of Hydrology, 120(1-4), 359-379.

Van’t Woudt, B. D. (1959). Particle coatings affecting the wettability of soils. Journal of Geophysicsal Research, 64, 263-267.

Authors: Lebron I1 and Robinson DA1

Reviewer: Reinsch S1

Affiliations

1 Centre for Ecology & Hydrology, Environment Centre Wales, Bangor, UK